Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Today's lab exercise should be carried out in pairs, ideally, but it's okay to do it by yourself, too. In the exercise below, you will see a number of items written in red letters , like the following:

In order to gain credit for this exercise, you must create a PDF document which provides the answers to all the questions and items written in red. Submit the PDF to the instructor via the "Assignments" tab in myCourses.

Today's assignment is meant to give you practice performing all the steps necessary to choose a good target for your project. It's not necessary to have chosen an object for your project yet; you'll have several more weeks to think it over. Consider this exercise as a practice run, just to give you some familiarity with the procedure.

In this practice exercise, I'll pretend that your target is going to be a variable star. In real life, you might choose a variable star, but you might instead select an asteroid, or a star cluster, or something else.

The goal is to choose a target for your observational project -- one that you and your teammate(s) will measure with our telescope later this semester. In order to pick a good star, you will make use of a number of tools:

Table of contents:

The big goal is for you to pick a variable star which you should be able to measure accurately with our equipment over the next few months. Let's go over some of the items to keep in mind as you try to choose from the tens of thousands of stars in the sky.

Your star ought to satisfy all of the following criteria:

In addition, it will be a great help if we can compare our results to those of other astronomers, and make use of additional measurements they might have made. So there's a bonus for targets which

There are two main types of stars from which you can choose:

So, first, pick one or the other. You can change your mind later if things don't work out for your original choice.

The next step is to look through a big catalog of variable stars to select a group of candidates. Eventually, you'll winnow this group down to just one or two possibilities.

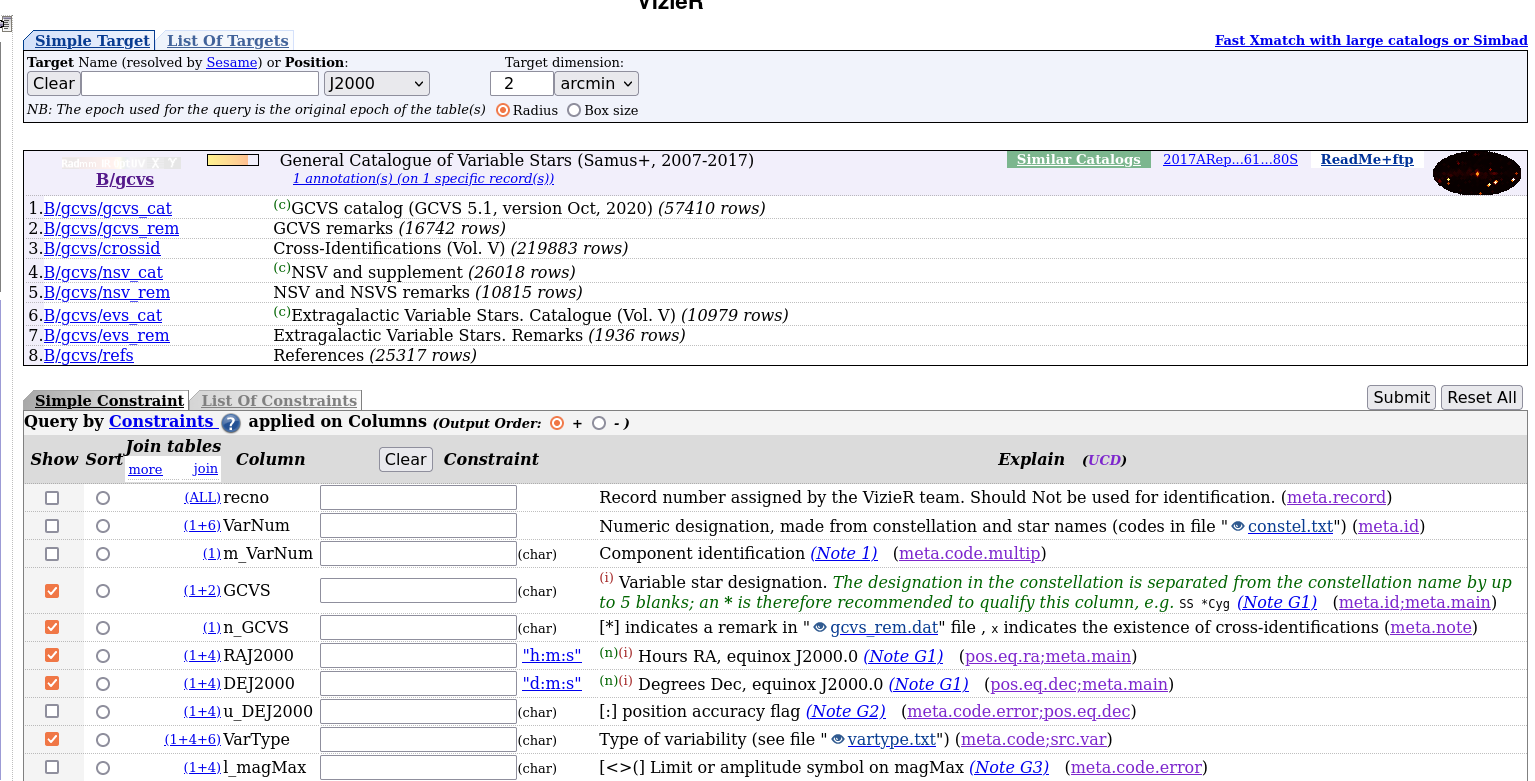

You should see a screen which looks like this:

Now, if you leave all the boxes empty, and just click on the "Submit" button, Vizier will interpret that as the request "show me every star in the catalog". It will simply print out a list of all the stars, but it will stop printing the list after a certain number of entries, just to save space.

Q: What is the default number of entries returned?

However, we don't want to sift through ALL the variable stars in this catalog. Instead, we want to add some CONSTRAINTS, which will select on those entries which satisfy some conditions.

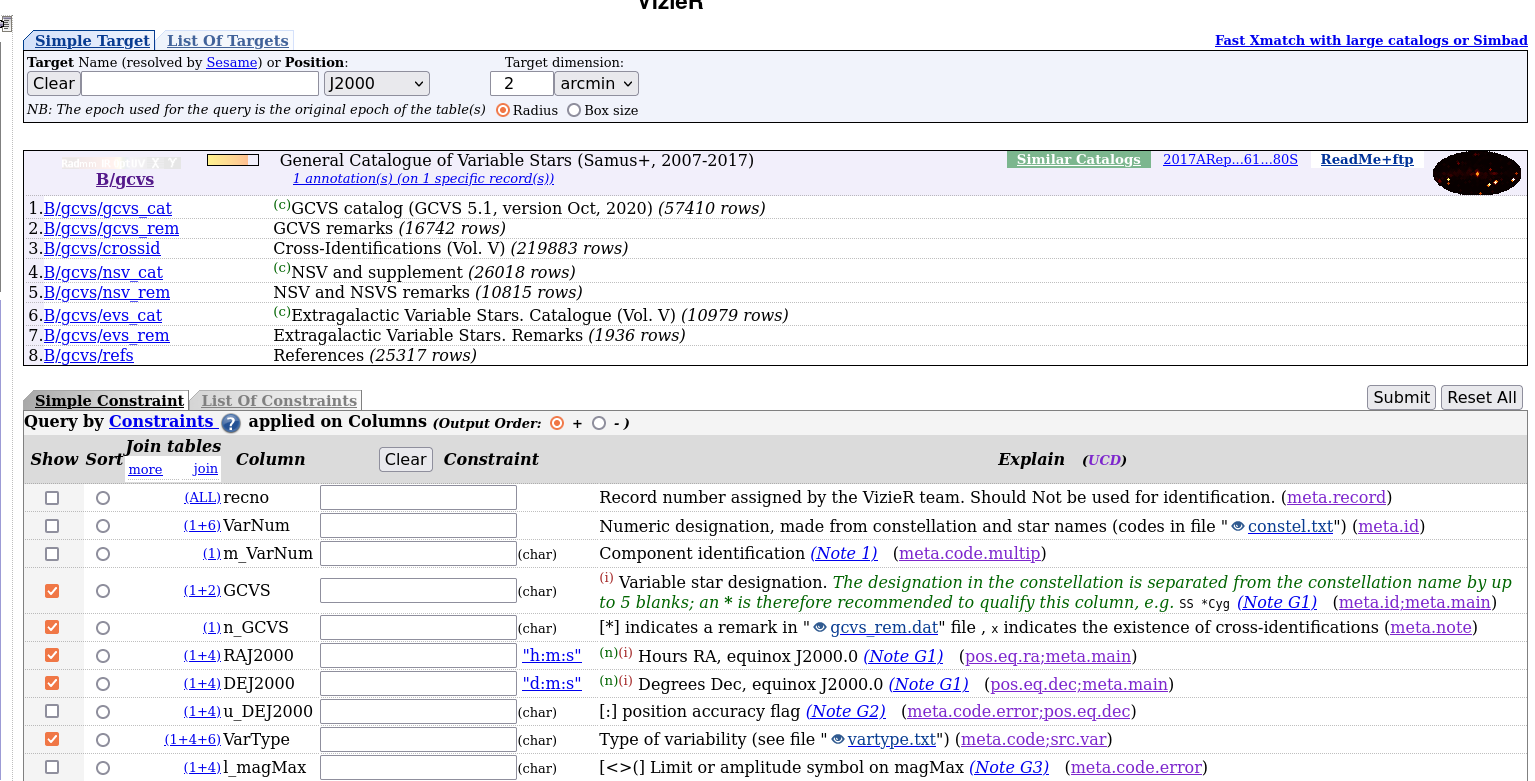

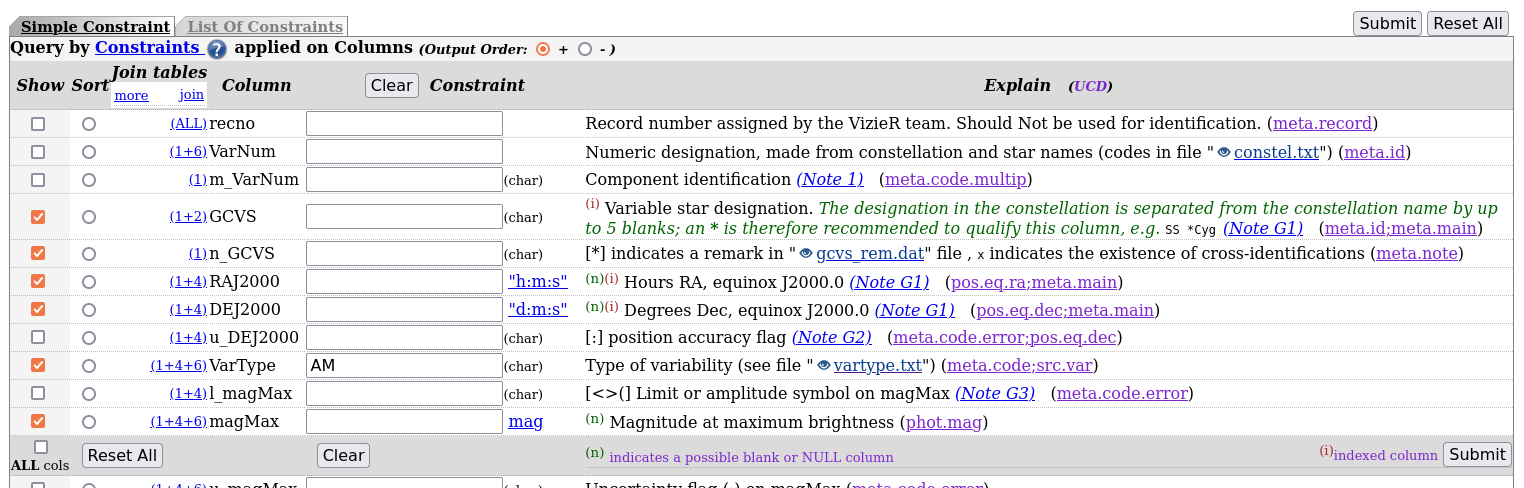

For example, suppose that you wish to select only stars which are eclipsing binaries. One of the rows in the database is called "VarType". If you click on the item labelled "see file vartype.txt", a new window will pop up, showing the various codes for different types of variable stars. By typing one of those codes into the Constraint box next to the word "VarType", you can choose ONLY stars which belong to a certain type.

Actually, there's a broken link on the Vizier website -- the "vartype.txt" file doesn't pop up when you click on the link. But I've made a local copy of vartype.txt

In the example below, I am choosing only stars which are of the AM Her type, for which the code is "AM".

Okay, now it's your turn. If you wish to choose an eclipsing binary star, type "E*" into the "VarType" box. If you wish to choose a pulsing star, type any of the following: "RR*", "DSCT". Then click on "Submit" in order to get a first idea of the number of possibilities.

Of course, most of these stars won't be visible from Rochester during the night-time sky in March and April. You need to add additional constraints to the query. If you have questions about the manner in which you can add a condition (such as "Dec is between 35 and 50 degrees"), click on the blue question mark next to the word "Constraints" in order to be shown some examples.

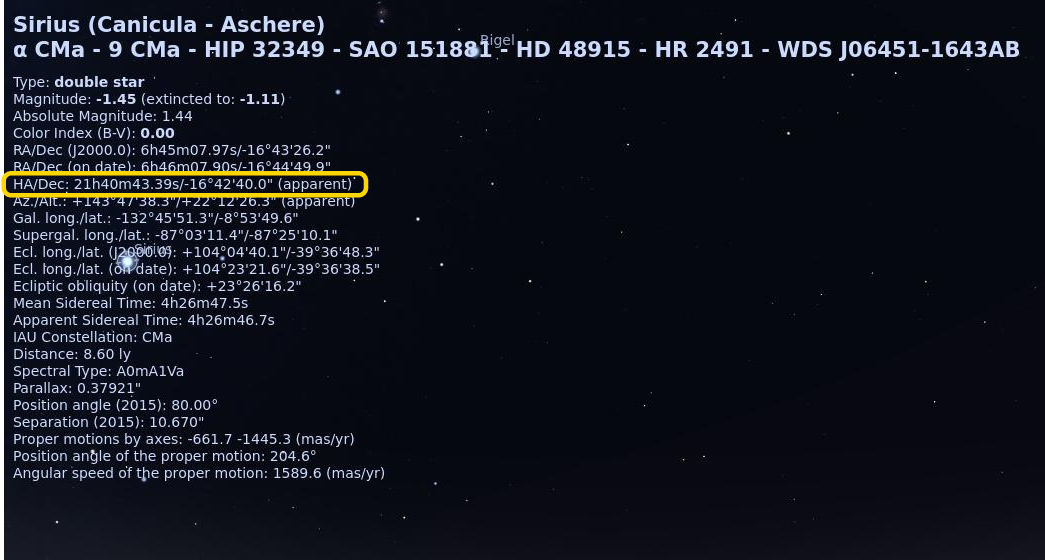

At this point, you ought to have a list of candidates; if the list contains only 1 or 2 items, please talk to your instructor. All of the objects on your list will be visible from Rochester at SOME time of year ... but will they be visible during the time when you can make your observations? In order to make your nights at the Observatory most efficient, your star should (ideally) be visible all night long In other words, it should be

In this example, the Hour Angle of Sirius is 21 hours 40 minutes and 43 seconds, or or 21:40:43. That lies in the valid range from 19 hours to 24 hours, so our telescope could indeed point to Sirius at this time.

A good way to check is to use Stellarium to make a map of the night sky. First, use Stellarium to fill in the following table with the local times for "just after sunset" (= Sun is 10 degrees below horizon after sunset), and "just before sunrise" (= Sun is 10 degrees below horizon before dawn).

just after sunset just before sunrise

Date

local time local time

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mar 1

Mar 20

Apr 10

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Okay, now you can use Stellarium again to figure out if any of your targets will be ready for you to observe. Set Stellarium to each of the above dates and times, and then locate your candidates. Is the candidate at least 15 degrees above the horizon at those times? As the candidate moves through the sky, does it stay within the range of Hour Angle that lies within our telescope's range of motion?

(Hint: the answer to these questions depends in large part on the Right Ascension (RA) coordinate of the target. You will quickly discover that only a relatively narrow range in RA values will put a star in the "right" portion of the sky).

At this point, you have a list of good possibilities. In order to increase the efficiency of our observing, we ought to form groups of 3-5 students who will work together on the same target.

So, walk around the room and talk with other people who have reached this point in the exercise. If you all agree on a particular target, then you can create a "team". (These don't have to the same people with whom you will work on your real project later in the semester ...) Each team should make a list of three candidates: the "top" choice, and two "runners-up".

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.