Taken from Figure 8 of Tutokov, A. V., Chupina, N. V., and Vereshchagin, S., V., Astronomy Reports, 67, 1418 (2024)

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

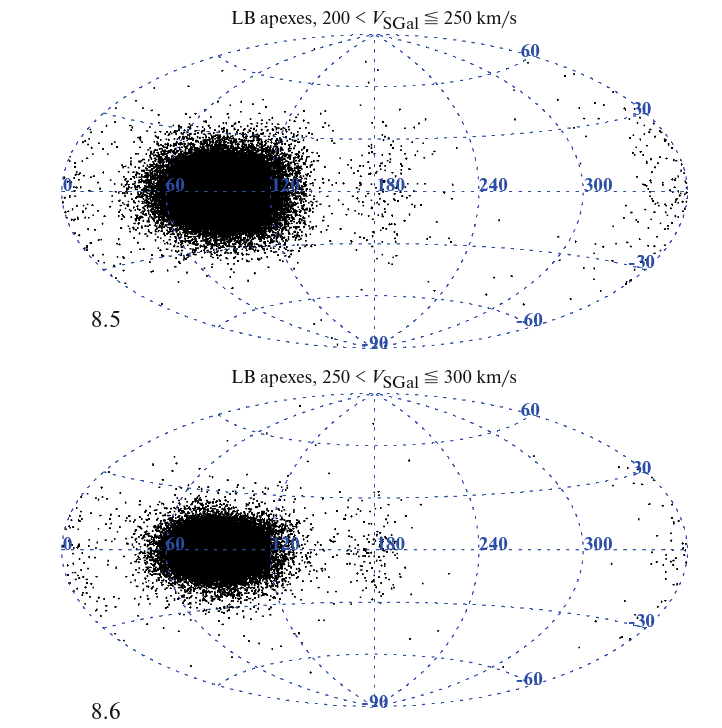

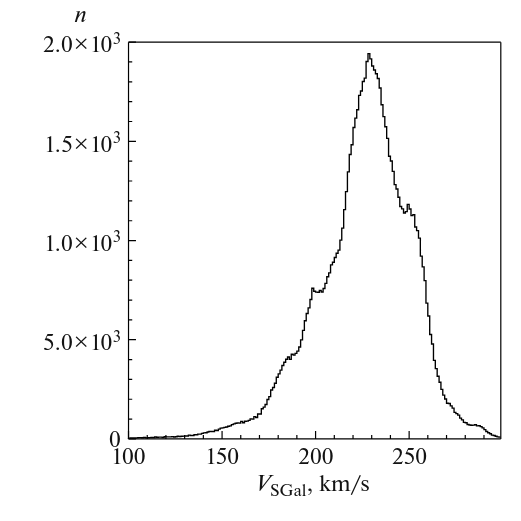

Most of the stars we see in the solar neighborhood are members of the Milky Way's disk population. They circle the center of the Galaxy in the plane of the disk, moving with a speed that varies with their distance from the center. Close to the Sun, that rotation velocity is around 200 - 250 km/sec. Measurements of stellar motions by the Gaia satellite show that the great majority of the stars we see take part in this orbital migration.

Taken from Figure 8 of

Tutokov, A. V., Chupina, N. V., and Vereshchagin, S., V.,

Astronomy Reports, 67, 1418 (2024)

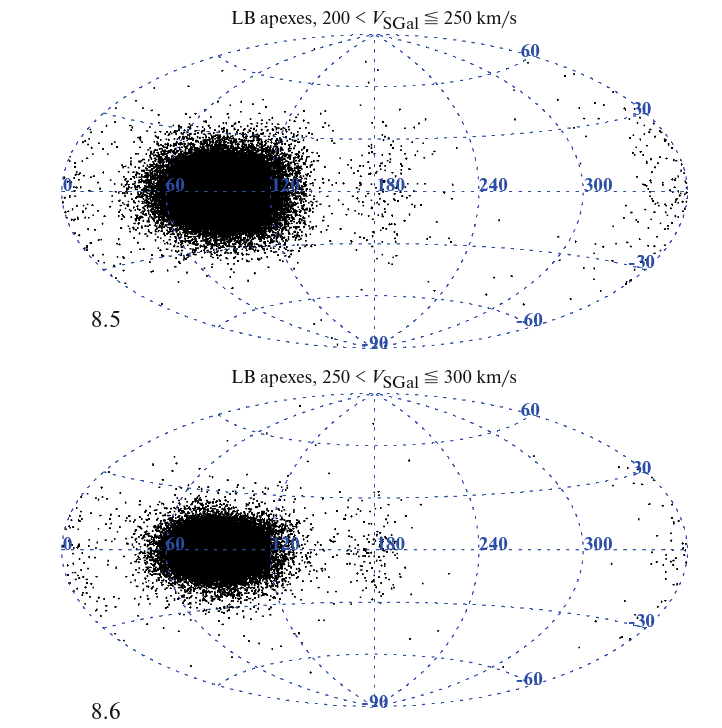

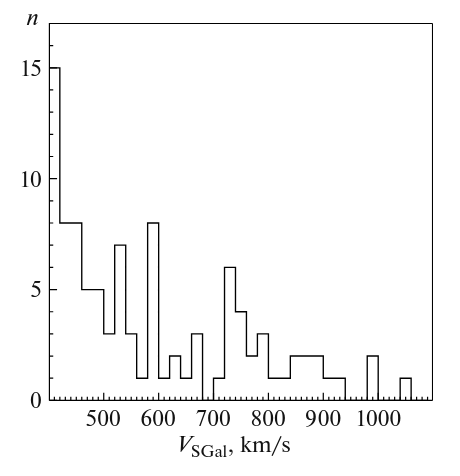

There are a small number of stars moving at higher speeds. Some are particularly frisky members of the disk population, but there are also a number of halo stars on orbits that dive into and out of the central region of the Galaxy.

Taken from Figure 8 of

Tutokov, A. V., Chupina, N. V., and Vereshchagin, S., V.,

Astronomy Reports, 67, 1418 (2024)

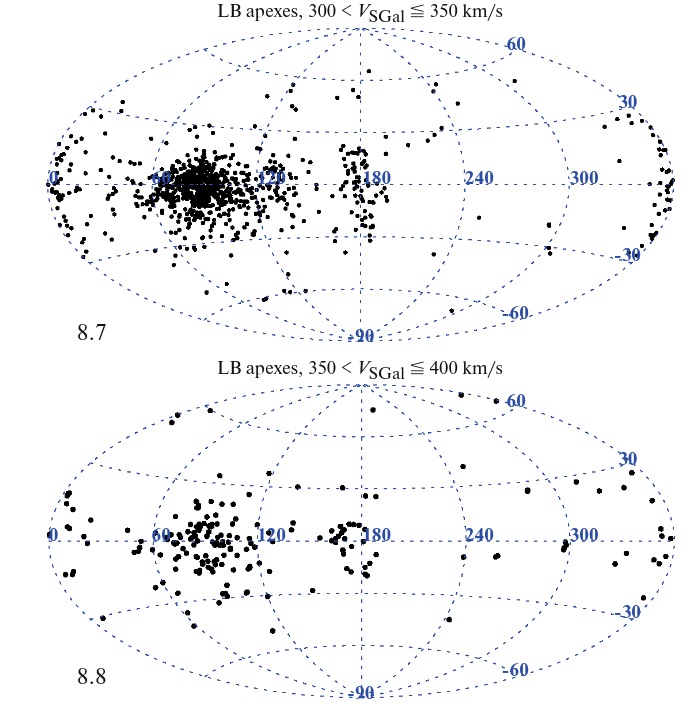

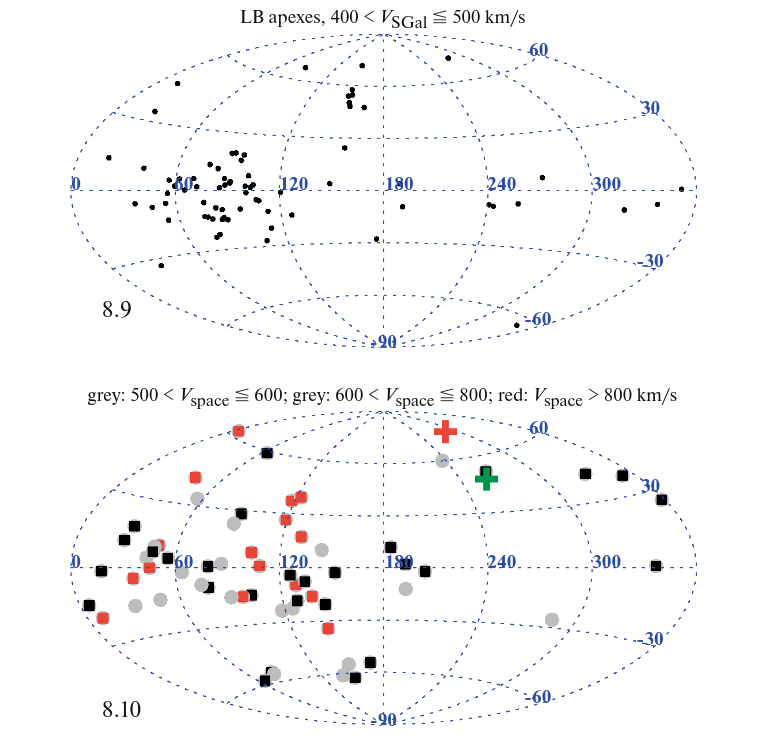

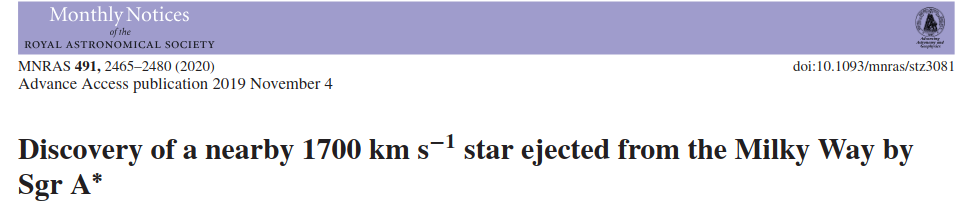

But there are a FEW stars -- really, not many -- which have enormous velocities, much, much faster than any disk star. Their orbits aren't clustered together in the same way as those of the disk stars; instead, they seem to be flying in all directions.

Taken from Figure 8 of

Tutokov, A. V., Chupina, N. V., and Vereshchagin, S., V.,

Astronomy Reports, 67, 1418 (2024)

When I wrote "a FEW", I meant it. Compare the number of these hypervelocity stars to the number of ordinary stars in one particular recent survey which included roughly one million objects.

Taken from Figure 6 of

Tutokov, A. V., Chupina, N. V., and Vereshchagin, S., V.,

Astronomy Reports, 67, 1418 (2024)

The question for the day is

Q: How did these stars gain such high velocities?

Astronomers have two main ideas, both of which depend on gravity to do the work.

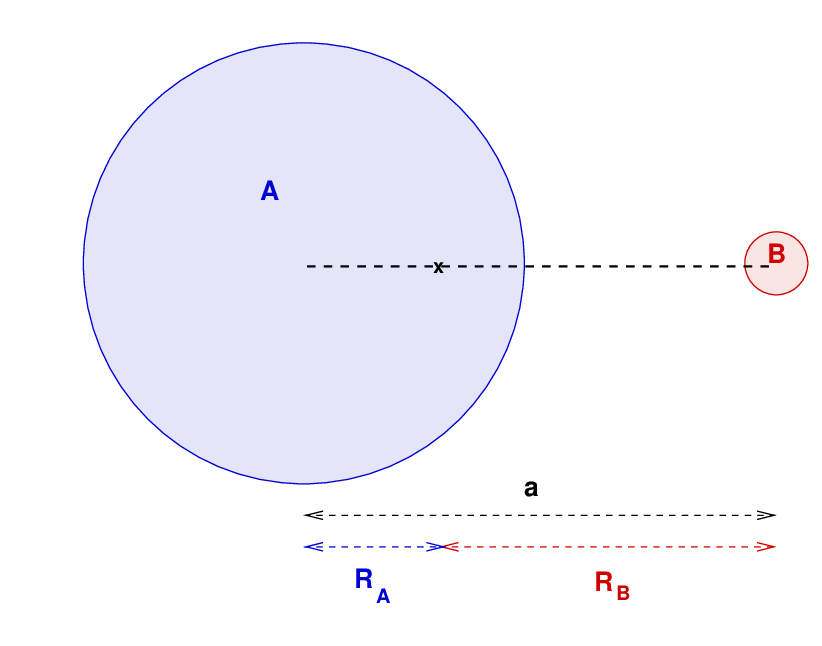

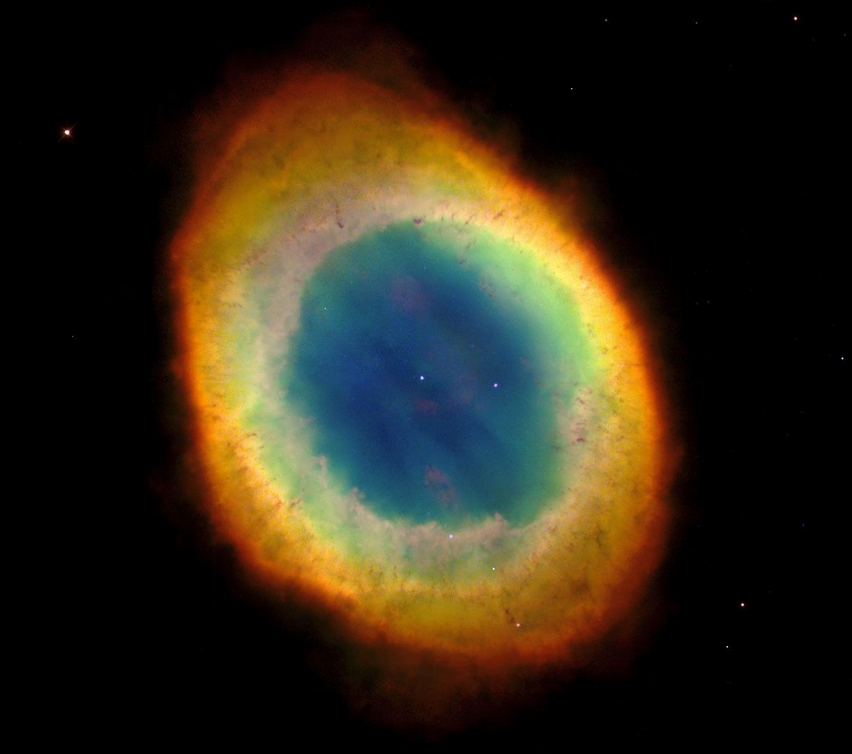

Stars in binary systems orbit around their common center of mass. If the two stars are far apart, then their orbital speeds are rather low; but if the orbit is a small one, their speeds can become considerable. Perhaps a close binary star could serve as the starting point for some physical process that could launch a hypervelocity star.

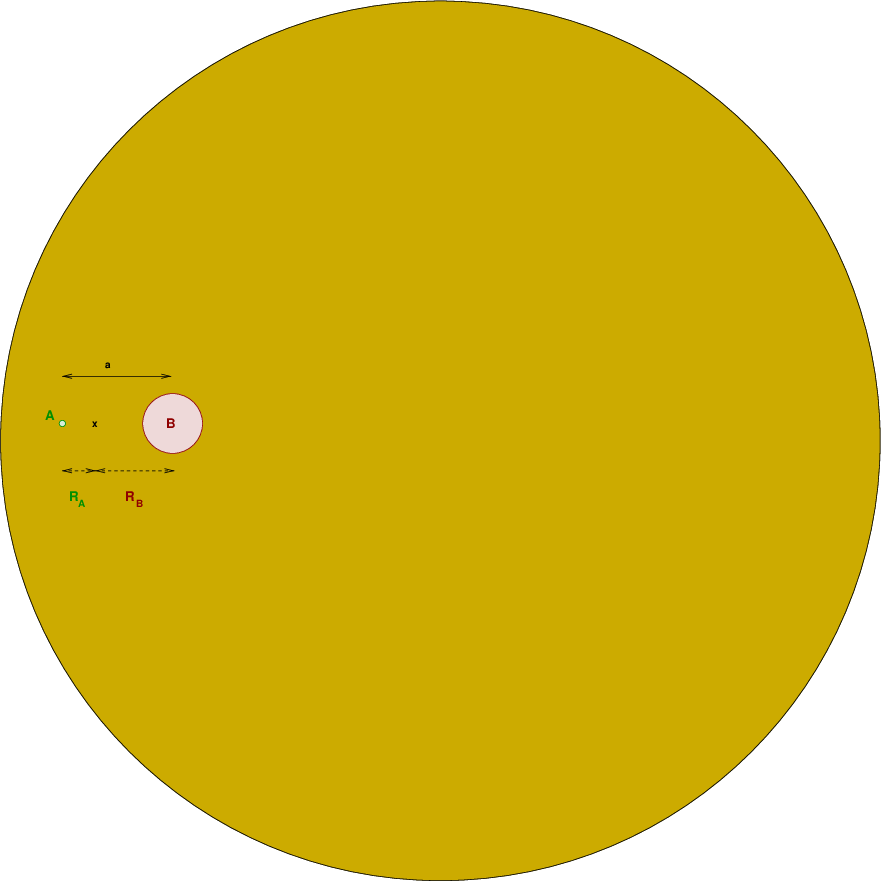

Let's find out. We'll look at a binary system which consists of a sun-like star and a much more massive companion.

We'll assume that these two stars have circular orbits around the center of mass; that's the usual situation when two stars are as close as this.

Let's try to figure out how fast each star is moving in its orbit.

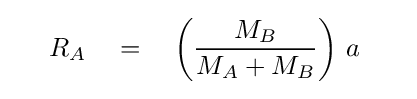

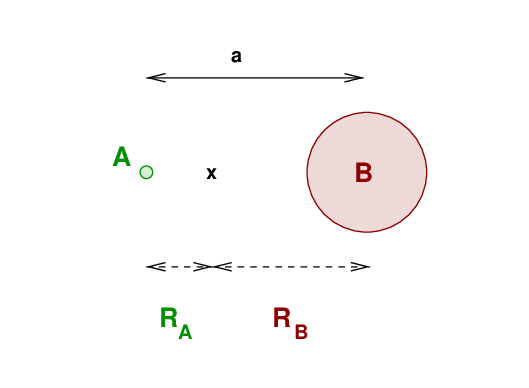

First, we need to know the distance of each star from the center of mass of the system.

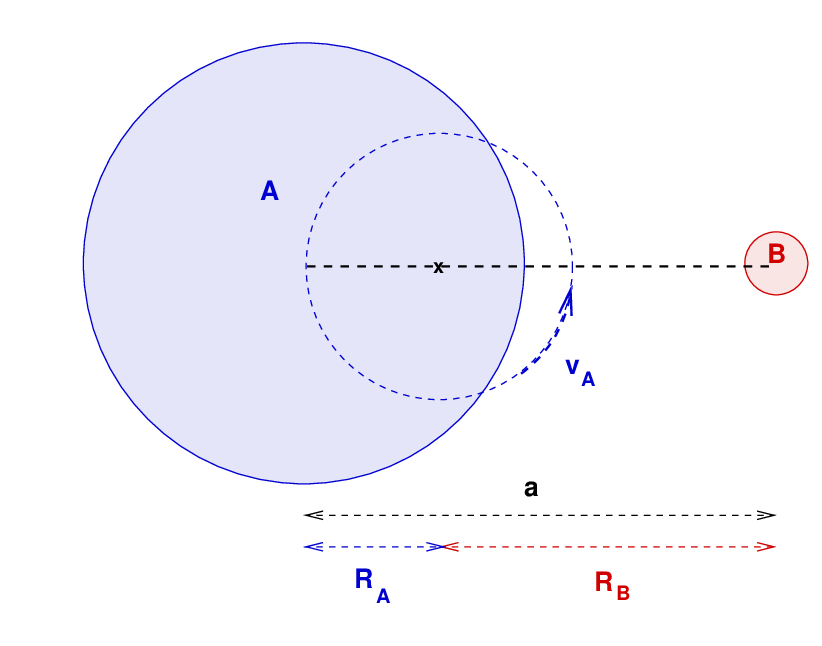

Each star moves in a circular path due to the gravitational force of its companion. We can set the centripetal force on each star equal to the gravitational force to find the star's orbital speed. For example, for star A,

Q: Can you solve for the orbital velocity of star A?

In a similar manner, one can solve for the orbital speed of star B.

Let's plug in the values for this system to calculate the orbital velocity of each star.

Q: What is the orbital speed of star A?

The star B has to finish its orbit in the same time -- but it has to cover a much longer distance, so it must have a larger velocity.

Q: What is the velocity of star B?

Well, this is quite a quick little star. Its speed around the center of mass of the binary system is quite high.

Now, in our example, one star was 15 solar masses. Stars with such high initial masses will run through their hydrogen fuel very quickly, switch to fusing helium, than carbon, then heavier elements. But, eventually, they will run out of all fuel, and the core at their center will collapse, creating a core collapse supernova.

Lots of complicated processes occur, but the end result is that most of the mass of the star is blown violently out into space at speeds of 5,000 - 10,000 km/sec, leaving a remnant of perhaps 2-ish (neutron star) to 8-ish (black hole) solar masses behind.

In a matter of just a few hours, the majority of the larger star's mass flies away, never to return.

Q: Assume that this explosion destroys the massive star A,

removing 13 solar masses from the system and leaving a

neutron star of only 2 solar masses behind.

What happens to the companion?

a) it continues to orbit the remnant of the exploded star

b) it flies off into space at a high speed

Hmmm. To answer this question, we can make use of the total mechanical energy of the system. For a gravitational system, the total energy is

Moreover, the total energy determines the nature of the system:

If we ignore all the real-life complications of a supernova explosion, and pretend that the companion star just keeps moving in its orbit, what happens?

Q: What is the gravitational potential energy of the double star now? Q: What is the kinetic energy of the companion star? Q: What is the total energy of the system?

So, in this situation, the companion star will fly away into the Milky Way at large. Its velocity will be roughly the combination of the binary's original circular orbit around the Galaxy with its velocity in the binary at the moment of the explosion. So, it could have a magnitude roughly between

minimum final velocity = (230 km/s) - (366 km/s)

maximum final velocity = (230 km/s) + (366 km/s)

Hmmm. The upper bound of this range is pretty big -- but it's still not large enough to explain some of the fastest hypervelocity stars we've found.

Suppose that we select a different type of binary star system -- one which includes some rather stellar peculiar components. Instead of relatively large, main-sequence stars, we'll choose two very compact objects:

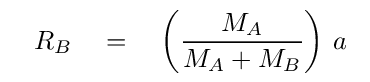

White dwarfs are relatively common; they are the end stage of the life for a low-mass star. Our Sun, for example, when it runs out of fuel in roughly 5 billion years, will -- after a brief period as a red giant -- gradually shrink, gently waft its outermost layers into space as a strong stellar wind, perhaps producing a short-lived planetary nebula. The inner layers and the very dense core will be left over, still hot with nuclear embers.

Image of M57 courtesy of

The Hubble Heritage Team (AURA/STScI/NASA)

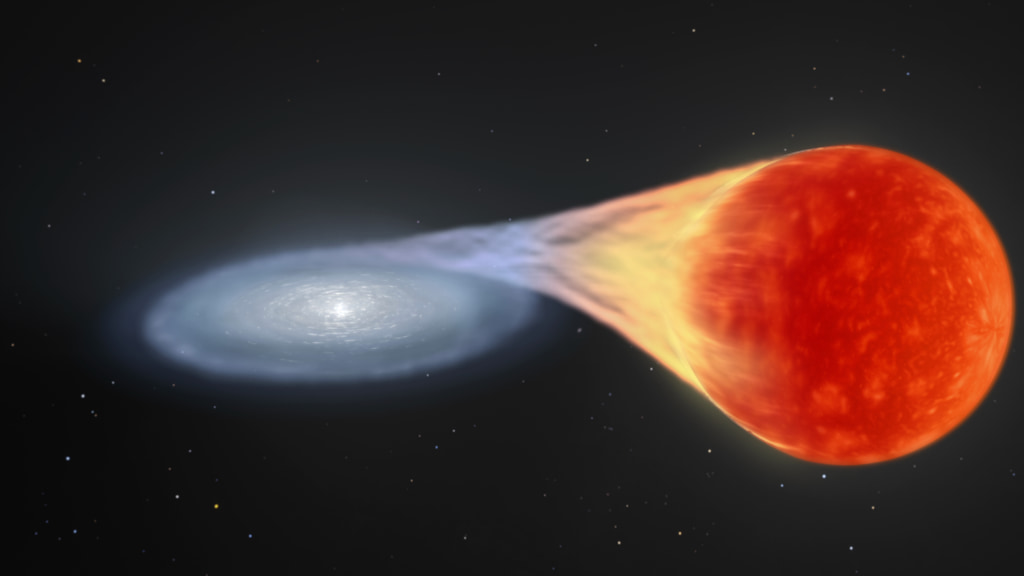

The white dwarf we've chosen is at the top end of the mass range for stability: the Chandrasekhar limit. If a white dwarf should gain a small amount of mass, its core can become hot enough for a runaway thermonuclear reaction to break out -- leading to a titanic explosion called a type Ia supernova.

The other star in this compact system is likewise a low-mass star which has evolved through much of its lifetime. In this case, the star's outer envelope of hydrogen-rich material has been removed due to the gravitational influence of its close companion, largely during the star's red-giant phase. All that remains are the innermost, helium-rich layers of material, on top of the helium-fusing core.

Even though the masses of the stars in this binary are smaller than those in the system we discussed earlier, the orbital speeds of the stars can be higher. Why? Because these stars are small compact that the separatation between them can be VERY small.

In our example, the distance between the white dwarf and the helium star is about one quarter of the Sun's radius!

Because the distance between these stars is small, the gravitational force between them is large. As a result, their orbital speeds can be very high.

Q: What is the orbital speed of the helium star B?

If the white dwarf should accrete enough material from its helium-star companion, its mass may increase to above the Chandresekhar limit ...

Image of accreting white dwarf binary courtesy of

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

Animator: Adriana Manrique Gutierrez (USRA);

Technical support: Aaron E. Lepsch (ADNET Systems, Inc.);

Producer: Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

... which would lead to a type Ia supernova explosion. Once again, the mass of one of the stars would simply disappear into the far reaches of space; and, unlike the case of a core-collapse event, this white-dwarf type of supernova leaves behind NOTHING: no neutron star or black hole. The orphaned helium star is free to add its entire orbital velocity to its motion around the center of the Milky Way.

This sort of compact binary system can produce stars with speeds of 800 or 900 km/s, maybe even up to 1000 km/s.

But is that enough to explain ALL the hypervelocity stars we have found?

The goal is to find a way to give one star a very, very, VERY large velocity. If we think of it in energy terms, the final state should provide one star with a very, very, VERY large kinetic energy. But how can we do that? Our first idea -- using the motion of two objects under their mutual gravitational forces -- does not seem to provide large enough final velocities to explain the most extreme hypervelocity stars.

Time for idea number two: consider THREE bodies.

Remember the total mechanical energy of a system of stars or other objects in space?

This total energy must be conserved over time, but we can shift portions of it from one object to another. Perhaps we can find some situation in which there are very large amounts of GRAVITATIONAL POTENTIAL ENERGY, and transfer a bit of that GPE into the KE of one particular star.

Q: What sort of celestial objects are associated with very

large amounts of GPE?

Yes, exactly: black holes. The more massive, the better for our purposes. What we could really use is a supermassive black hole.

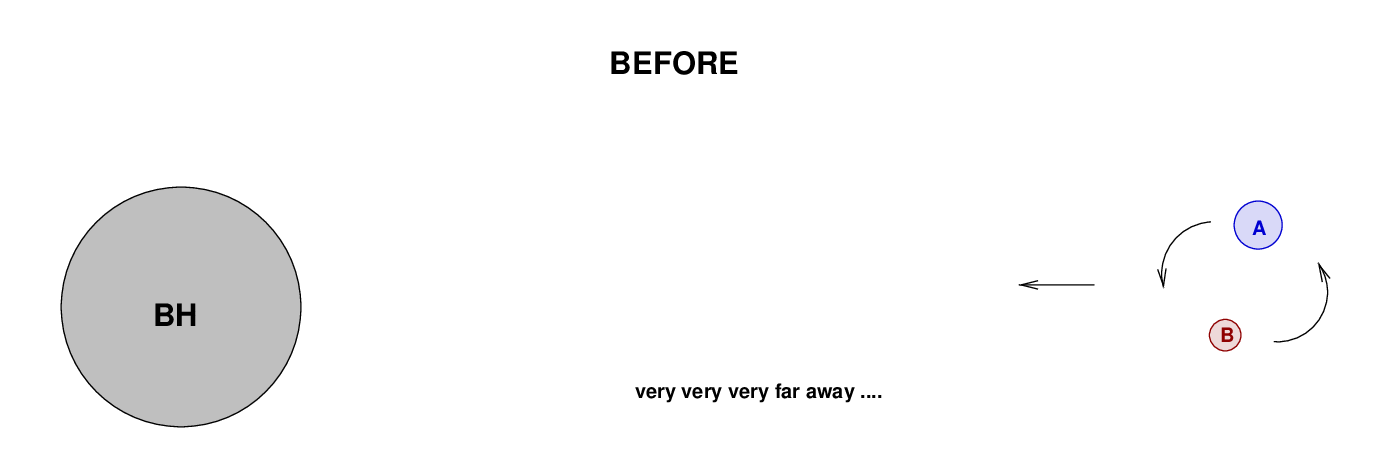

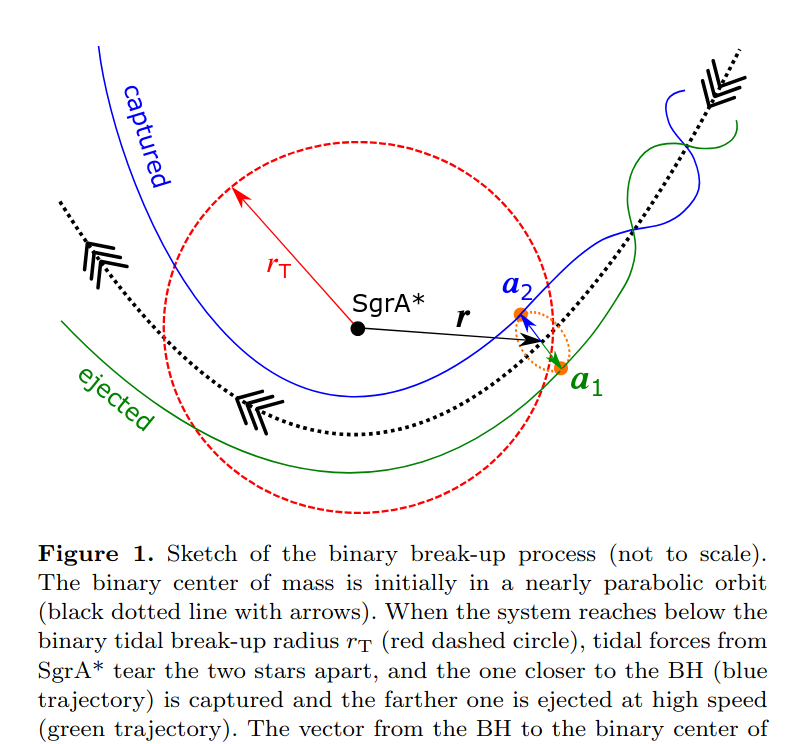

Here's the basic idea: a binary star is initially far, far away from the black hole.

At this moment, the total mechanical energy of the system is

Eventually, the binary falls toward the black hole. As it speeds past the black hole, one component happens to be going "backwards" in its orbit, and so has a total speed which is a little SLOWER than that of the center of mass. The other component, which happens to be going "forward" in its orbit, has a total speed which is a little FASTER than that of the center of mass.

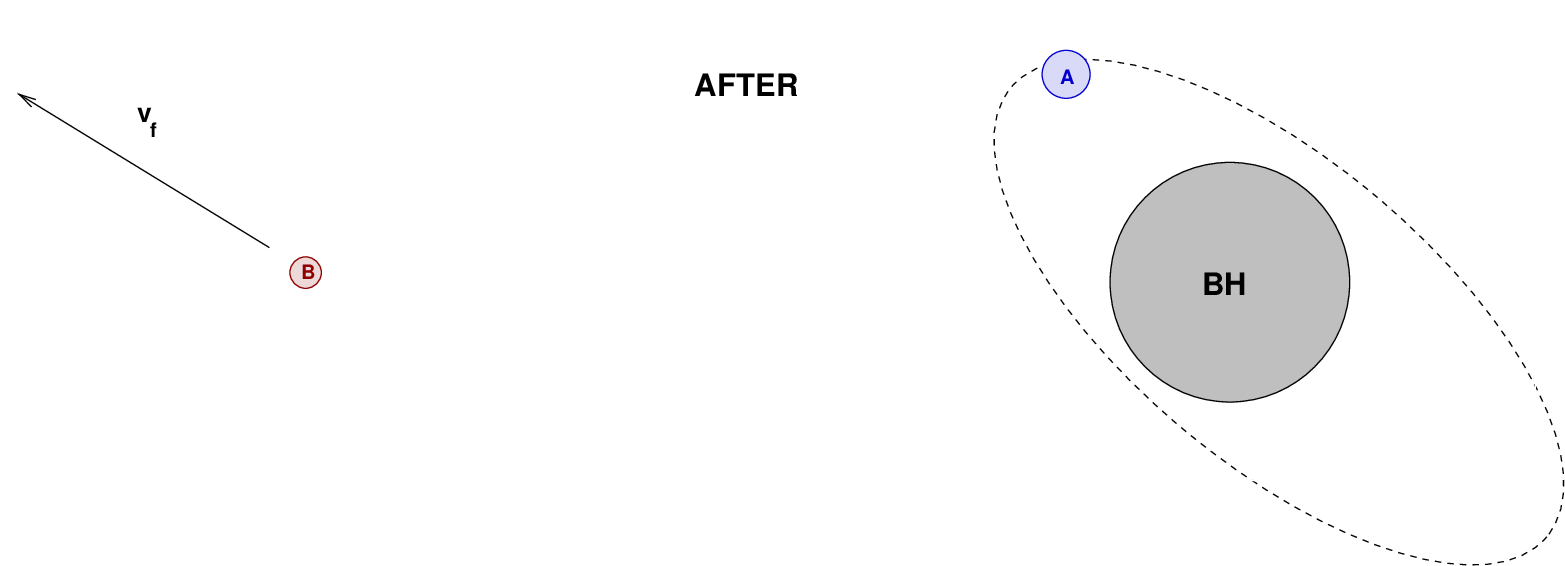

As a result, the slower component is captured into an orbit around the black hole, while the faster component escapes to infinity.

Now, in this final state, the total energy is

Because the GPE of star A orbiting the black hole is so large, compared to the initial total energy of the two stars orbiting each other, this switcheroo may end up leaving star B with enough KE that it has a very large final velocity.

Let's find out by putting in some representative numbers:

Star A: M_A = 3 solar = 5.97 x 1030 kg Star B: M_B = 1 solar = 1.99 x 1030 kg Black hole: M_BH = 106 solar = 1.99 x 1036 kg Initial size of A-B orbit: a1 = 1.39 x 1010 m Size of A-BH orbit: a2 = 4.49 x 1013 m

First, in the initial state, what is the total energy? One can work out the speed of each star in its orbit:

Q: What is the initial total energy of the system?

(KE of each star, plus GPE of the two stars)

The final orbit of star A around the black hole (which would initially be very elliptical, but we'll consider as circular for simplicity) has a velocity of

Q: What is the final KE of star A, plus the GPE

of A-and-black-hole?

Q: How much KE does star B have in the final state?

Q: How fast is star B moving?

Is THIS scenario -- the encounter of a close binary star with a supermassive black hole -- able to account for the fastest hypervelocity stars we have found?

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.