Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Last time, we looked at the unusual "hypervelocity stars" which fly through the Milky Way with much larger speeds than their ordinary neighbors. We focused on one star in particular, which we speculated could escape the Milky Way entirely and perhaps, someday, reach another galaxy.

Just how fast would a star have to fly in order to do that?

We'll begin with the simplest situation: two point masses, M1 and M2, separated by a distance R. The gravitational potential energy is defined to be

where the constant of universal gravitation is

Simple enough to compute ... but what does it mean? The units are those of energy (Joules), but ... what does this amount of energy represent?

Q: Suppose the GPE between two objects is -100 Joules.

What does that MEAN?

The answer is that the GPE between two objects is proportional to the energy it would take to separate them until they were an infinite distance apart. In this example, one would have to perform 100 Joules of work in order to pull the two objects apart to a very large distance from each other.

By this convention, the GPE of two objects which are very, very far away from each is zero. If they move toward each other, the GPE becomes negative; as they come closer and closer, the GPE becomes more and more negative. If they could somehow reach a separation of R = 0, then in theory the GPE would become infinitely negative. In real life, of course, lots of other physical processes prevent two objects from occupying the same space.

Besides, real objects aren't point sources, anyway.

In our previous lecture, we investigated the phenomenon of "hypervelocity stars," which travel through the Galaxy at very high speeds. One of the processes which can accelerate a star into this state involves a close binary system, in which each component orbits the common center of mass at a high speed. If one of the two components should EXPLODE, dispersing all its mass to an effectively infinite distance, then the remaining star may inherit its orbital velocity as it flies off on its own.

But this mechanism requires all (or at least the great majority) of a star's material to move far, far away from all the rest of it. The gravitational forces of all that matter will pull back, against the explosion, trying to prevent the star from exploding. Just how much energy does it take to exceed the gravitational pull of an entire star?

Let's first work out the general solution for a simplified model of a star, and then put in the numbers to get a real answer.

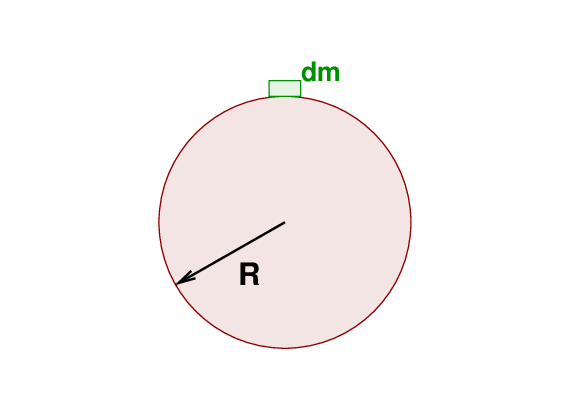

We'll start with an even simpler example: a solid sphere of radius R and mass M, upon which sits a little chunk of mass dm.

Q: How much energy will it take to pull the little block

away from the sphere to an infinite distance?

Right.

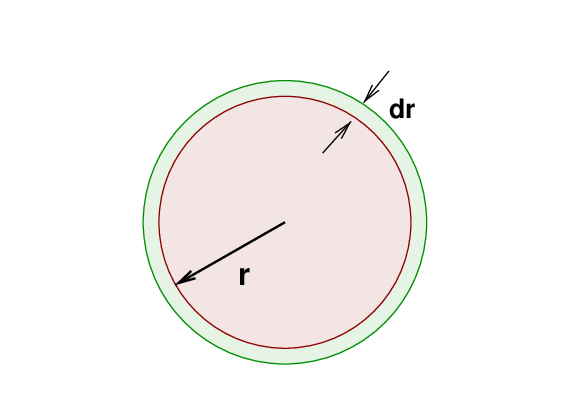

Okay, now we make things a bit more interesting. Suppose that we again have a solid uniform sphere of radius r, but this time we don't know the mass directly; instead, all we know is that it is made of material with a density ρ. Instead of placing a little block of mass on top of the sphere, this time we place a spherical shell of mass over the entire outer surface, with the same density ρ and a thickness dr.

Q: What is the mass of the sphere? Q: What is the mass of the shell of extra material? Q: What is the GPE of this added shell?

Right again.

Okay, now we put it all together: suppose we build a sphere of uniform density ρ, starting with a teeny tiny sphere at the center and subsequently adding layers of thickness dr, until the final radius of the object is R.

Q: Can you integrate to find the GPE of the entire structure?

Express your result in terms of the total mass M

of the sphere and its radius R.

You should find

This is usually called the gravitional binding energy of a uniform sphere.

Great. Now we know how to compute the binding energy of a star (if we approximate a star as a sphere of uniform density). For any particular stellar size and mass, we can calculate the amount of energy required to blow it completely apart. Let's do it -- not just for one star, but for three examples.

Energy required to

Star Mass (kg) Radius (m) blow it apart (J)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sun 1.99 x 1030 6.96 x 108

core-collapse

progenitor 2.99 x 1031 4.87 x 109

thermonuclear

progenitor

(white dwarf) 2.79 x 1030 6.37 x 106

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

That sounds like a LOT of energy.

Hmmm. The Sun produces a LOT of energy every second via nuclear fusion inside its code. If one could somehow "save" all that energy over a period of time, and then suddenly "release" it, could that be enough to blow the Sun apart? For how long would one have to "save" all that energy?

Q: The solar luminosity is about L = 3.8 x 1026 J/s.

How long would it take the Sun to generate enough energy

to blow itself apart?

It turns out that real supernovae generate a huge amount of energy in a very short time. The wide variety of supernova cover quite a range of energies, but a typical value is

typical SN energy release = 1044 J = 1051 erg = 1 foe

As you'll see if you compare this value to your calculations in the table above, this is more than enough to send any star to infinity (and beyond). In real explosions, this energy is divided into several portions:

Just how much energy does a typical supernova release? It's hard to compare it to familiar phenomena -- dynamite, TNT, even nuclear weapons are completely insignificant. But perhaps if we consider an ENTIRE GALAXY, we might find a worthy opponent.

The Milky Way Galaxy has roughly 100 billion stars. Pretend that

each one is identical to the Sun.

Q: How much energy does the Milky Way emit in one second?

Q: How long would one have to "save" the luminosity of the

Milky Way Galaxy in order to accumulate as much

energy as a typical supernova?

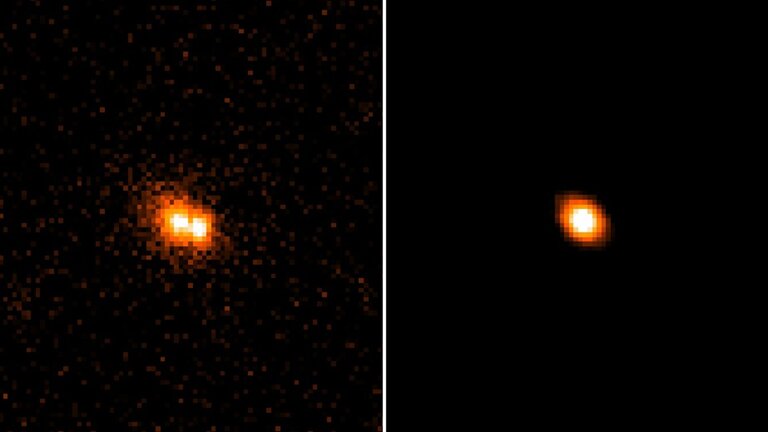

That's ... pretty impressive. Only a small fraction of the entire energy generated in the explosion is radiated as visible light, but it's not wrong to say that "a supernova can outshine its entire host galaxy for a brief time."

Image of SN Gaia14aaa courtesy of

M. Fraser/S. Hodgkin/L. Wyrzykowski/H. Campbell/N. Blagorodnova/Z. Kostrzewa-Rutkowska/Liverpool Telescope/SDSS

Images of high-redshift SNe and their host galaxies

courtesy of

NASA, ESA, and A. Riess (STScI)

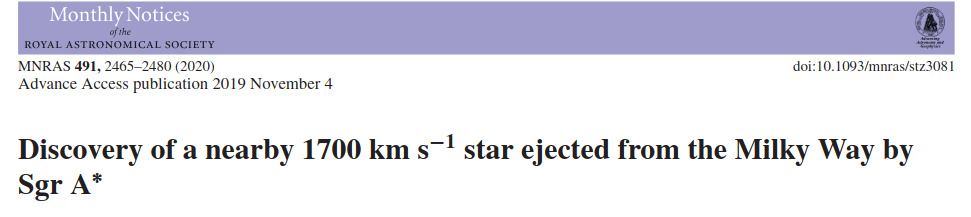

Remember that one star with a REALLY high velocity?

Taken from

Koposov, S. E., et al., MNRAS 491, 2465 (2020)

Is a speed of v = 1700 km/s fast enough to cause a star to leave the Milky Way Galaxy entirely? Will this star fly off into intergalactic space? Is there a chance that it might wander into some other galaxy eons from now?

Answering this question properly is rather difficult, because the density of the Milky Way is NOT uniform, as far as we can tell. In order to compute the gravitational influence of all the Galaxy's mass on the star properly, one would need to determine that density accurately, and then integrate over the entire radial extent of the Milky Way.

However, if we make a "toy model" of the Galaxy, we can at least take an educated guess. Suppose that we treat the Milky Way as ONLY the mass interior to the Sun's location, and pretend that there is no significant amount of material at larger radii. In that case, we can compare the KE of the star at its current location (near the Sun) to its GPE, and see if its total energy is positive (escapes!) or negative (bound).

The mass interior to R = 8 kpc is roughly 1011 solar masses,

or M = 2 x 1041 kg. Assume that the hypervelocity

star has a mass of about 2 solar = 4 x 1030 kg.

Q: What is the KE of the star?

Q: What is the GPE of the star?

Q: Is the total energy positive or negative?

Now, the real Milky Way does NOT stop at Sun's distance of 8 kpc from the center; it extends outward for many tens of kpc into space. The density decreases at larger radii, but the total mass grows considerably. Our best estimates are that the total mass of the Milky Way may be close to 1012 solar masses at distances of order 100 kpc from its center.

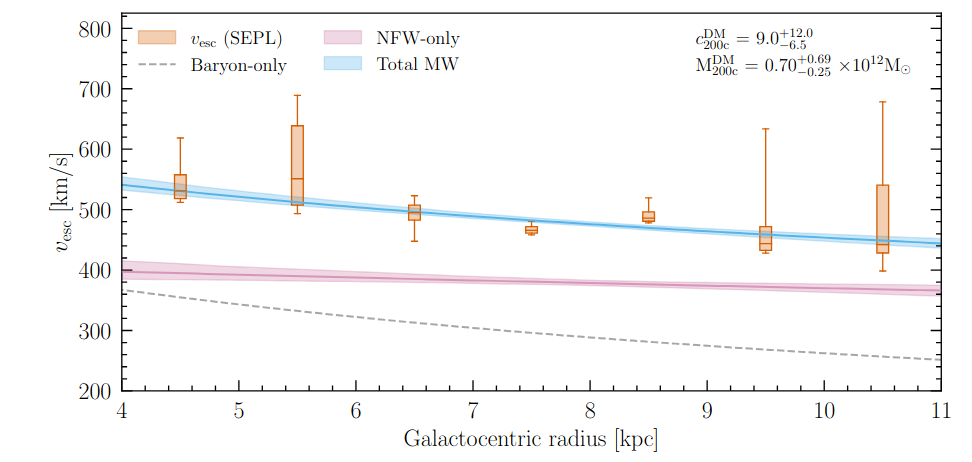

Several groups of scientists have attempted to determine the escape velocity from this very extended, very massive galaxy for stars in the solar neighborhood. One method is to measure the distribution of stellar velocities: under certain circumstances, the shape of the tail of this distribution can provide a good clue to the actual escape velocity.

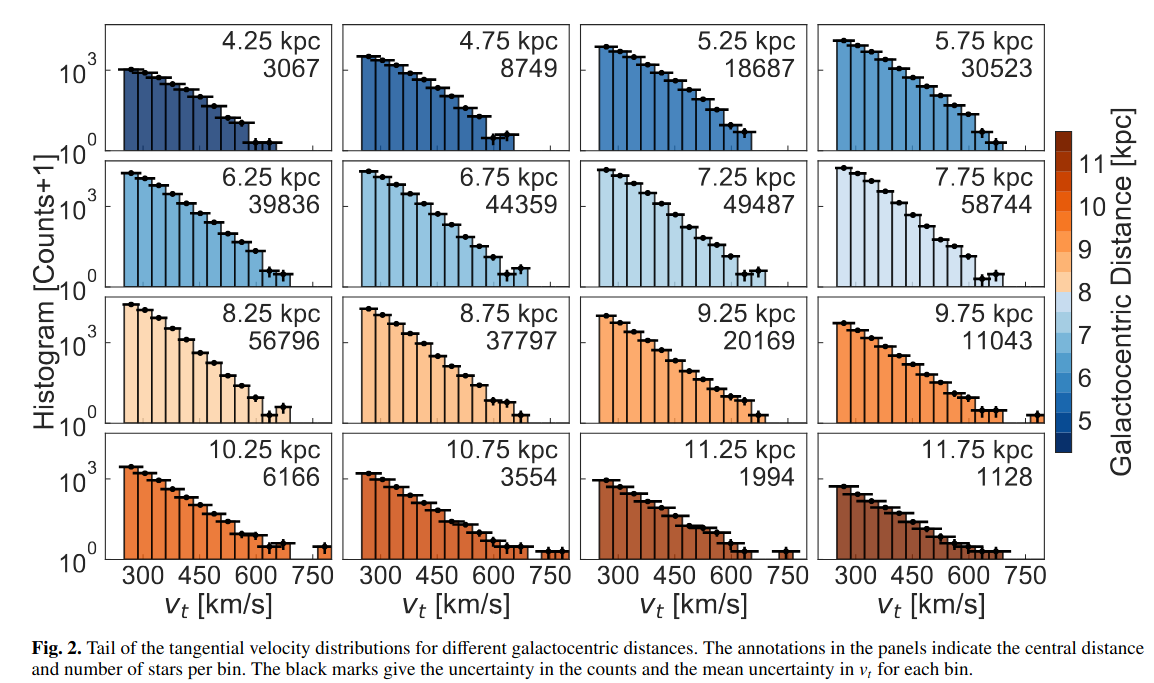

Gaia provides a wealth of information about stellar velocities at a range of galactocentric distances ...

Figure 2 taken from

Koppelman, H. H., and Helmi, A., A&A 649, A136 (2021)

... which allows one to estimate the escape velocity at those locations.

Figure 5 taken from

Roche, C., et al., ApJ 972, 70 (2024)

Q: Based on this figure, will the hypervelocity star S5-HVS1

escape from the Milky Way?

Back in the dark ages, when television shows were broadcast over the air, I was a big fan of

Promotional image courtesy of

Cancelled Sci Fi

The premise of the show was that humans were storing spent nuclear waste on the Moon ... until an accident in the lunar dump site caused the entire mass of nuclear material to explode! (Click on the image below to watch a short but exciting video clip)

Image and video clip of

Space: 1999, "Breakaway"

courtesy of

Group Three Productions and

Shout! Studios

The explosion pushes the Moon out of Earth's orbit, and, in fact, out of the entire Solar System. Over two seasons worth of episodes, the citizens of Moonbase Alpha fly past a number of stars and extrasolar planets, experiencing a number of fantastic adventures.

BUT ... there might be a bit of a problem with the physics of this unplanned excursion.

Let's compare two different amounts of energy:

We'll start with the kinetic energy required to send the Moon beyond the Solar System. The Moon will escape the Sun's pull if the total energy of the Moon-Sun system equals zero:

For simplicity, we'll ignore the presence of the Earth in our calculations below. It turns out that the Sun dominates these energy considerations.

Moon: Mass 7.35 x 1022 kg

Radius 1.74 x 106 m

Speed(*) 2.98 x 104 m/s (in orbit around Sun)

Sun: Mass 1.99 x 1030 kg

Moon - Sun distance 1.5 x 10^11 m

Q: What is the GPE of the Sun-Moon system?

Q: How much KE does the Moon have as it orbits the Sun?

Q: How much MORE KE must one give the Moon to cause it to escape?

That seems like a lot of energy. How does it compare to the gravitational binding energy of the Moon? That will give us some idea of the amount of energy which could tear the body of the Moon apart.

Q: What is the gravitational binding energy of the Moon?

Do you see the problem here?

As it turns out, there are a number of other, um, problems with sending the entire Moon out into interstellar space; just how fast it would have to be moving for it to reach even one other stellar system in the lifetime of the Alphans is quite a puzzler. But I was only a kid in elementary school, and unaware of all these issues.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.