Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

All the waves we've seen so far have not moved. We call them "stationary", or "standing" waves. They oscillate in place, but they don't MOVE.

How can we use mathematics to send these disturbances sliding to the right, or to the left? How can we make the peaks of the oscillations shift to new positions? We need to find some functional form of position and time

which describes behavior like this:

Let's start with a simpler question. Suppose we have some function y(x) -- say, for example, a gaussian, which has mathematical form

Q: At what position x does this function attain its peak value?

It reaches its peak at x = 0, of course.

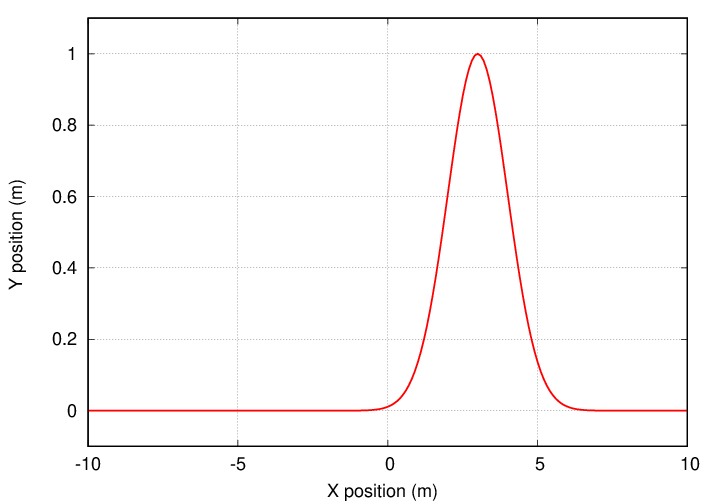

But suppose that we want to move the gaussian, so that it is centered at some other location? How could we modify the equation so that the new peak is located at x = 3?

Q: What is a mathematical expression for this shifted function?

The answer is -- change the x to (x - 3).

Q: Suppose we want the peak to be located at x = 6?

Okay, here comes the big question. What if we wish the position of the peak to change with time, like this? (click on the image below to see the motion)

It might help to answer a few simple questions. Can you fill in the table below?

At time peak is at equation is

--------------------------------------------------------

t = 0 s x = 0 m y = e-x2

t = 1 s x = 3 m y = e-(x - 3 m)2

t = 2 s x = 6 m y = e-(x - 6 m)2

t = 3 s x =

t = 4 s x =

and in general

t = T s x =

---------------------------------------

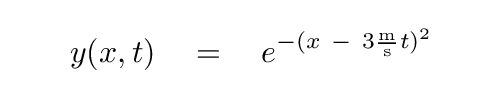

So, the answer to our question "How can we write mathematically the equation of a moving gaussian?" turns out to be -- in our particular case --

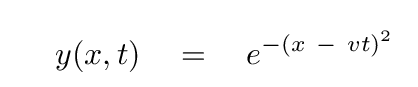

or, in the more general case,

where v is the velocity of the peak along the x-axis.

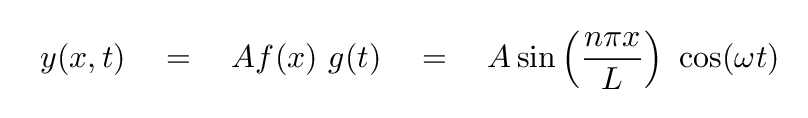

So, how can we turn the mathematical equations we have derived in the past few weeks for STANDING waves into equations which describe TRAVELLING waves?

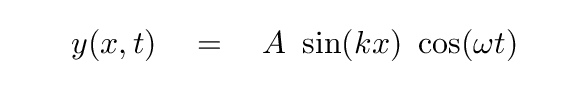

As you may recall, the equation for a stationary wave can be separated into one part which varies only with position, and a second part which varies only with time.

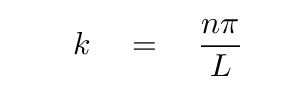

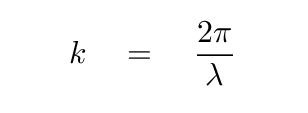

In some situations -- and as you have already seen -- scientists will use a combination of factors to define what is called the wave number: the coefficient which multiplies position x inside the equation for a wave. In our current case, this turns out to be

but in the general case, wave number is written in terms of the wavelength:

Q: What are the units of the wave number?

Using the wave number, one can write the equation of a stationary wave in a slightly more simple manner:

In order to write the equation of a travelling wave, we simply break the boundary between the functions of time and space, mixing them together like chocolate and peanut butter.

Yes, yes, we could use cos instead of sin; and we could also add a phase offset φ if necessary to match some initial condition.

If we do choose to describe a wave in this manner, then the position of any particular feature will change with time. That makes it a travelling wave, as we desire. But how fast will it move?

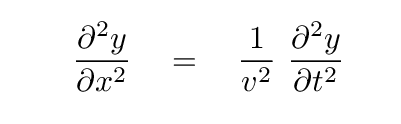

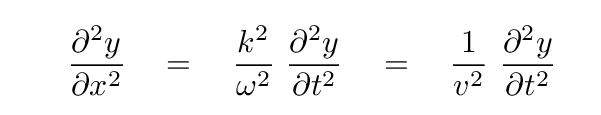

Well, remember the wave equation?

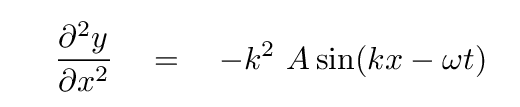

Q: What is the second derivative of y(x,t) with respect to x?

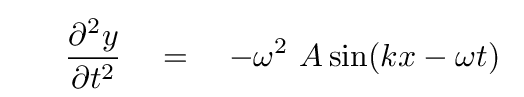

Q: What is the second derivative of y(x,t) with respect to t?

Q: What is the speed of the wave? In other words, how fast does the

x position of one feature of the wave change with respect to time?

The answers are

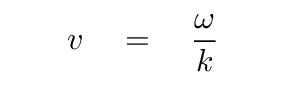

which imply

And so the speed of features of the wave along the x-direction is

Q: Do the units match on both sides?

There is another way we can start with the equation

for a stationary wave and derive equations for travelling waves.

This one involves math;

more specifically, a trigonometric identity.

That identity is ...

"Wait a minute!" I can hear you thinking.

"Does that really work?"

Well, let's find out.

Yes, it works. I've tried it, too.

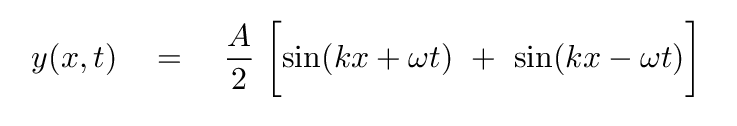

Okay, now that we believe this is a valid mathematical identity,

we can put it into practice.

We begin by writing the equation for a stationary wave:

It doesn't matter whether we choose sine for the spatial part

and cosine for the time part;

we can use either "sine" or "cosine" for each portion,

find an appropriate trig identity, and follow the same path

which we are about to take.

So, let's apply

We end up with

The second term in the brackets has a factor of

kx - ωt.

It represents a wave moving to the right

with speed

v = ω/k.

Why, it's simply an identical wave,

travelling at the same speed,

but in the opposite direction.

Yes, it's slightly annoying that a wave travelling

in the POSITIVE x-direction has an equation

with a minus sign in it;

and a wave travelling in the NEGATIVE x-direction

has an equation with a plus sign in it;

but we must simply put up with it, and think twice

when interpreting equations.

Now, what happens if we add these two identical,

but oppositely-moving, waves?

One ends up with a stationary wave

with double the amplitude of each travelling wave.

This is a good time to re-visit a result

we derived earlier.

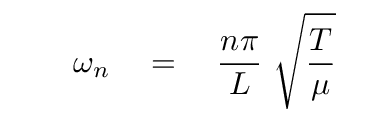

When

speaking of waves on a string,

we noted that in order to meet the boundary conditions --

that the string could not move at each end --

the frequencies of normal modes must have the form

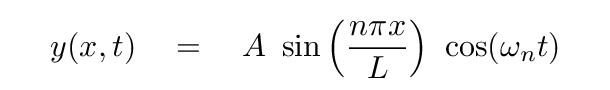

If we start with the equation for a stationary wave on the string

and re-write it as the sum of two waves travelling in

opposite directions

and then substitute the expression above for the angular frequency

ωn of the n-th normal mode,

we end up with the rather unwieldy

However, we can simplify this a bit;

note that each term inside the "sine" parantheses

contains a common term

of nπ/L.

If we factor this out, we get

If we look at things this way,

the variables x and t

appear only in a particular combination.

This reveals something we already knew:

the speed of waves travelling along a string depends on

the tension and linear mass density.

Another way to make waves travel

Pick a random number between 5 and 12. Call it "A".

Pick a random number between 40 and 50. Call it "B".

Q: What is sin(A) * cos(B)?

Q: What is sin(A+B) + sin(A-B)?

Q: What about the first term in the brackets? What does it represent?

The speed of a wave on a string

For more information

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.