Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Observing in the mid-infrared from space

Today, let's focus on space-based

observations of the mid-infrared;

by that, I mean wavelengths from around 3 to 50 microns.

It is possible to work at these wavelengths

from the ground (at least the shorter-wavelength side),

but very difficult.

Space is really the right place to do this work.

The devices used to register light in the "mid-IR"

are the same as those

mentioned for the near-IR.

The materials used vary with wavelength,

with the most common choices being

wavelength (microns) material operating temp (K)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 - 2.5 HgCdTe 78

3 - 6 InSb 30

6 - 25 Si:As 6

50 - 200 Ge:Ga 6

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

While the materials have remained the same over several decades

of instrument development,

the sizes of the detectors have grown considerably.

We'll be focusing on three satellites designed for

mid-infrared astronomy:

Although each satellite had several instruments,

I'll compare here the main imaging devices on each.

number of pixels resolution mode

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

IRAS 62 x 4 bands approx 5 x 2 arcmin scanning

Spitzer 256x256 x 4 bands approx 1.5 arcsec pointed

WISE 1024x1024 x 4 bands approx 6 arcsec scanning

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The big difference is simply that more recent instruments

have larger fields of view and more pixels;

in other words, the newer satellites

can collect more data, more quickly.

Let's look briefly at the properties of three

infrared satellites.

- IRAS

- IRAS was a joint project of NASA, the UK, and the Netherlands.

It was a survey instrument,

designed to map the entire celestial sphere at wavelengths

of 12, 25, 60, and 100 microns.

The telescope looks like an ordinary optical telescope,

with primary diameter 57 cm and secondary diameter 24 cm.

Note that the secondary isn't particularly small,

unlike those in ground-based infrared telescopes.

On the other hand, optics in IRAS were kept cooled

to 2-5 Kelvin, so they did not produce much

infrared radiation.

Fig II.C.3, optics of IRAS, taken from

IRAS Explanatory Supplement

The focal plane of IRAS was rather simple.

It didn't really have a "camera" --

instead, it had a set of individual "pixels"

of different types arranged in rough rectangle.

The spacecraft was spun, so that the sky swept

past the detectors in the direction shown.

As time passed, the satellite slowly scanned

the entire sky.

Fig II.C.6, Focal plane of IRAS, taken from

IRAS Explanatory Supplement

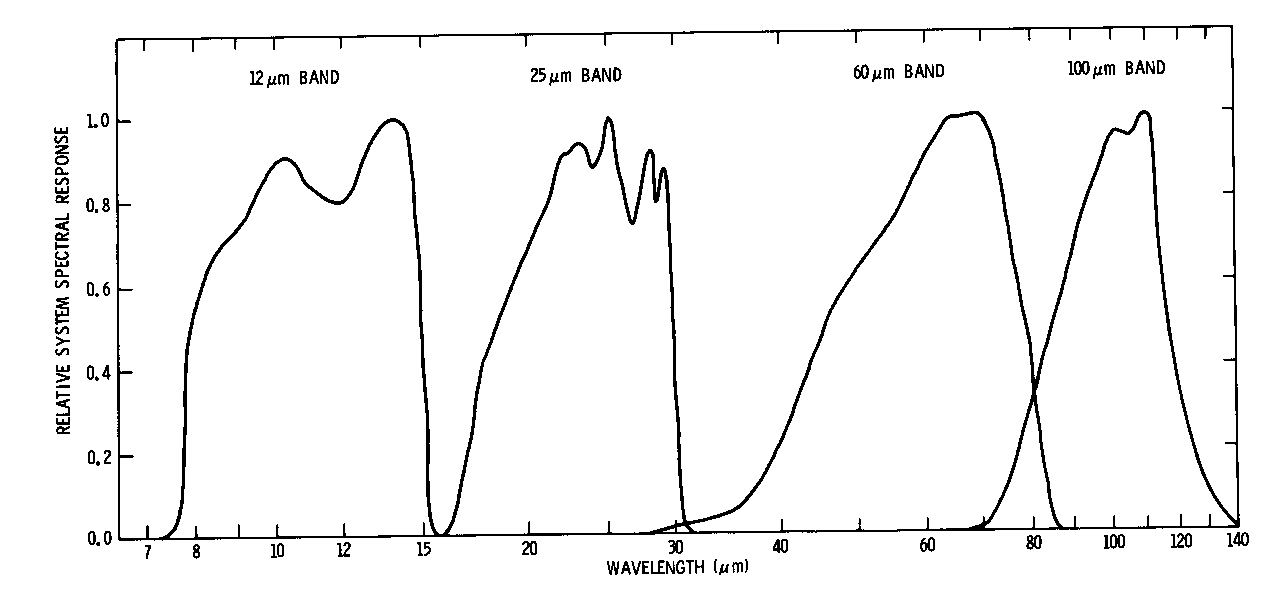

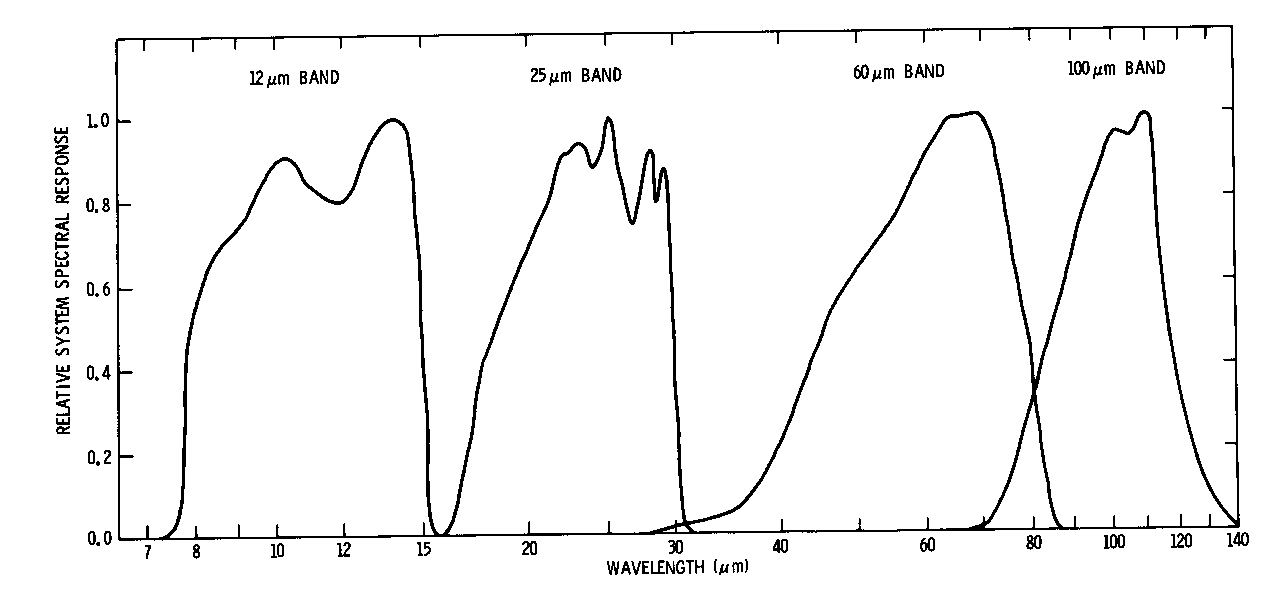

The IRAS passbands ranged from 12 to 100 microns,

but each one was rather broad.

Fig II.C.9, passbands of IRAS, taken from

IRAS Explanatory Supplement

IRAS made 4 to 6 measurements of each spot on the sky

during its 10-month lifetime.

When its crygenic cooling material ran out,

the mission ended.

Q: Use the SkyView Query Form to request an image

of M31 (the Andromeda Galaxy) taken with the "IRAS 25 micron" survey.

Use 800 pixels and a 5 degree field.

(my version)

Q: Use the SkyView Query Form to request an image

of M1 (the Crab Nebula) taken with the "IRAS 25 micron" survey.

Use 800 pixels and a 0.25 degree field.

(my version)

- Spitzer

- Spitzer, launched in 2003 and terminated in 2020,

was one of NASA's "Great Observatories", each

a big project intended to serve the astronomical community

for many years.

Q: What are the other "Great Observatories"?

As befitted a "Great Observatory",

it collected a lot of light: its primary mirror was 85 cm

in diameter, the largest of the three infrared satellites

we'll discuss.

It was a pointed instrument,

which views a tiny portion of the sky in great detail,

but can not carry out large surveys easily.

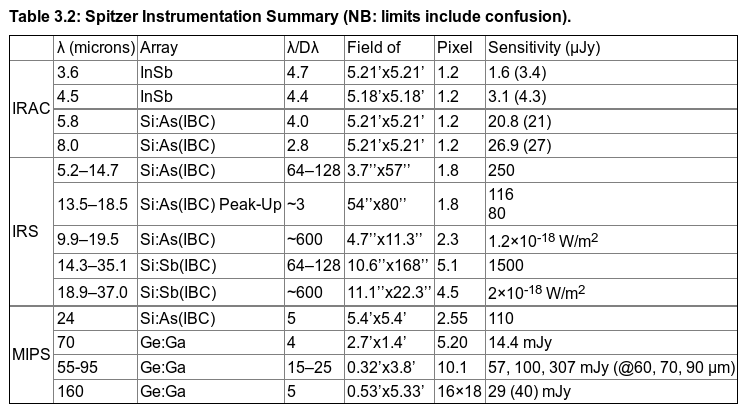

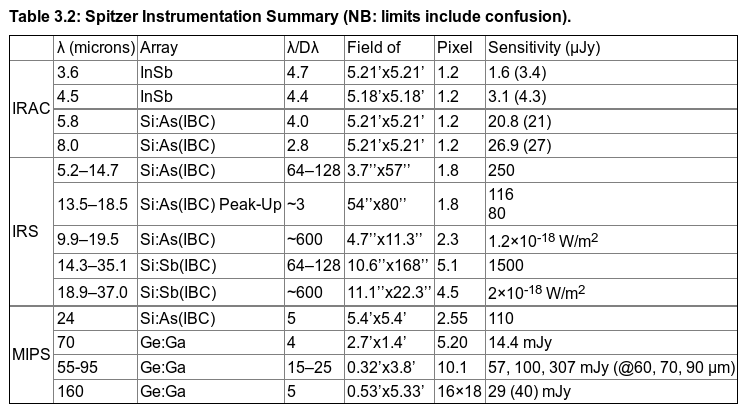

Spitzer carried three main instruments: IRAC (near-IR camera),

IRS (near-IR spectrograph) and MIPS (mid-IR camera).

The field of view of each instrument was roughly 5x5 arcminutes

(which is about twice as large as each "pixel" of IRAS!)

Table 3.2 taken from

The Spitzer Telescope Handbook

Note that the longer-wavelength instruments must be cooled

to very low temperatures: below 6 K or 12 K (the MIPS 160 micron

detector required the very lowest temperatures).

About six years after launch, in 2009, the spacecraft used

the last of its cryogen materials, and the detectors

started to warm up.

Between September, 2009, and January, 2020,

the focal plane was kept

at 28.7 Kelvin,

which was still low enough for the InSb detectors in

IRAC's short-wavelength bands (3.6 and 4.5 microns)

to observe fruitfully.

So, for the final 11 years of its lifetime, Spitzer carried out

a limited "warm mission", in which it observed only

with these two arrays.

But on January 30, 2020,

NASA terminated the mission;

the annual $14 million cost of operating the observatory

was judged too large for the perceived returns.

Q: Find an image of M31 (the Andromeda Galaxy) taken with

Spitzer's MIPS camera at 24 microns.

(my version)

Q: Find an image of M1 (search for "Crab Nebula") taken with

Spitzer's MIPS camera.

(my version)

-

Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)

- WISE was launched in 2009 and operated from Jan 14, 2010 to

Feb 1, 2011;

after several years of sleep, it was re-activated

in September, 2013, for the "NEOWISE" mission, focusing

on asteroids and other objects in our solar system.

The second mission was terminated on July 31, 2024.

Like IRAS, it was a survey instrument,

designed to make a map of the entire sky at several epochs.

It managed to make around 10-12 measurements of objects

near the ecliptic equator during its (first) lifetime,

with many more for objects near the ecliptic poles.

WISE had a 40 cm primary mirror, cooled to very

low temperatures to minimize its thermal emission.

Light entering the aperture was split into four passbands,

each of which is focused onto a separate focal plane

of very large size: about 47 x 47 arcminutes.

In each case, the light fell onto a hybrid array

of 1024 x 1024 pixels:

name wavelength material

----------------------------------------

W1 3.4 microns HgCdTe

W2 4.6 microns HgCdTe

W3 12 microns Si:As

W4 22 microns Si:As

----------------------------------------

Note that the passbands are not all equally wide:

Image courtesy of

WISE and Ned Wright

Q: Use the SkyView Query Form to request an image

of M31 (the Andromeda Galaxy) taken with the "WISE 22 micron" survey.

Use 800 pixels and a 5 degree field.

(my version)

Q: Use the SkyView Query Form to request an image

of M1 (the Crab Nebula) taken with the "WISE 22 micron" survey.

Use 800 pixels and a 0.25 degree field.

(my version)

About nine months after its launch in 2009,

the cryogenic coolants inside WISE were depleted;

as a result, it lost its ability to observe in its

longer-wavelength bands (12 and 22 μm).

However, it continued observing the sky

in the 3.4 and 4.6 micron bands for another four months.

In February, 2011, NASA placed the spacecraft into "hibernation mode"

and halted the mission ...

... BUT, several years later, in December, 2013,

NASA woke up the spacecraft and restarted its operation.

The new

NEOWISE

mission focused on searching for asteroids in

the solar system,

with a special emphasis on those which might pose

a hazard to the Earth.

The second mission was terminated on July 31, 2024.

The section below was written years before JWST launched ...

Well, it seems difficult not to peer just a year (or two, or three)

into the future for the next big thing in infrared satellites:

James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)

will take a VERY large mirror, 6.5 meters in diameter,

into space,

and send the light it collects to a suite of 4 main

instruments.

Those instruments cover the range of ...

Q: What is the wavelength coverage of JWST's instruments?

The answer

as

illustrated here

and at

this ESA document.

We can't cover everything, of course, but let's talk about

just a few of the most common features of emission in

near- and mid-infrared wavelengths.

- thermal continuum from stars

- atomic line absorption in stellar atmospheres

- atomic emission lines from hot clouds of gas

- molecular line absorption in stellar atmospheres

- thermal emission from dust

The first three are basically the same as the common emission

mechanisms in the optical.

Stars emit a continuum due to blackbody radiation;

much of it lies in the optical, but a fair amount

falls into the IR, too.

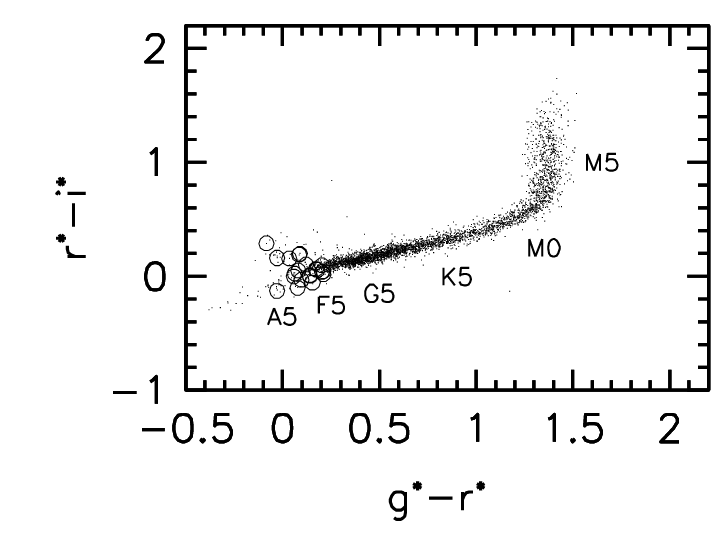

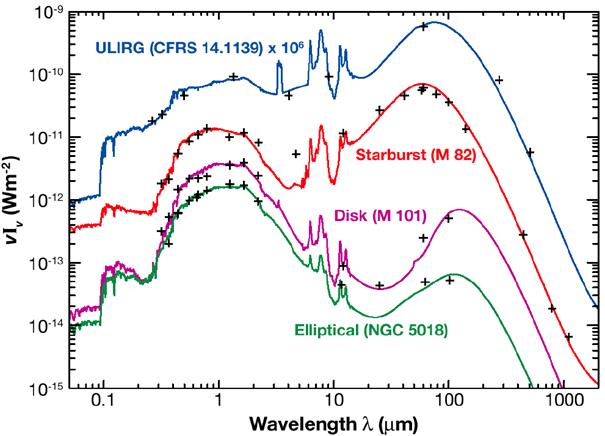

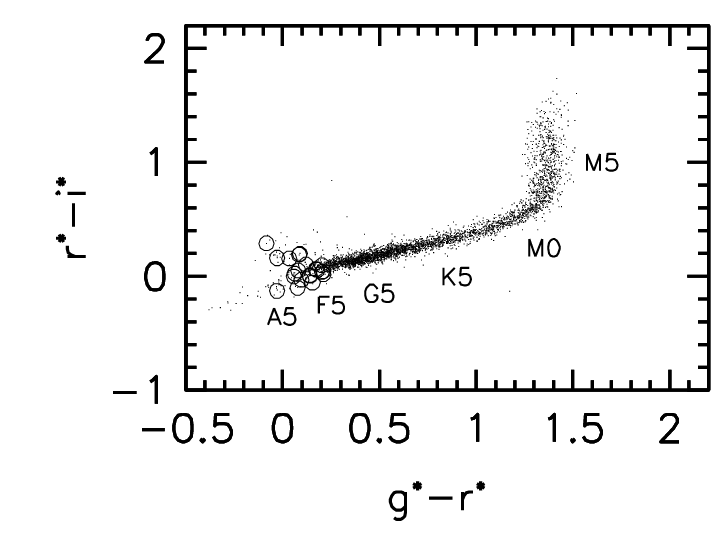

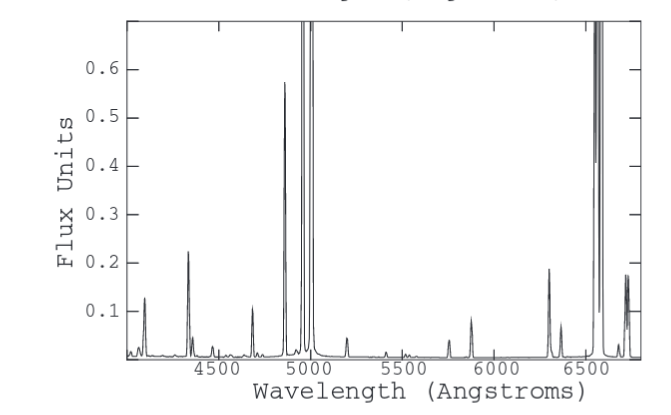

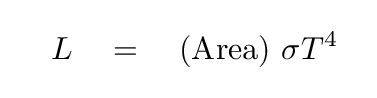

Taken from Figure 1 of

Finlator et al., AJ 120, 2615 (2000)

Taken from Figure 5 of

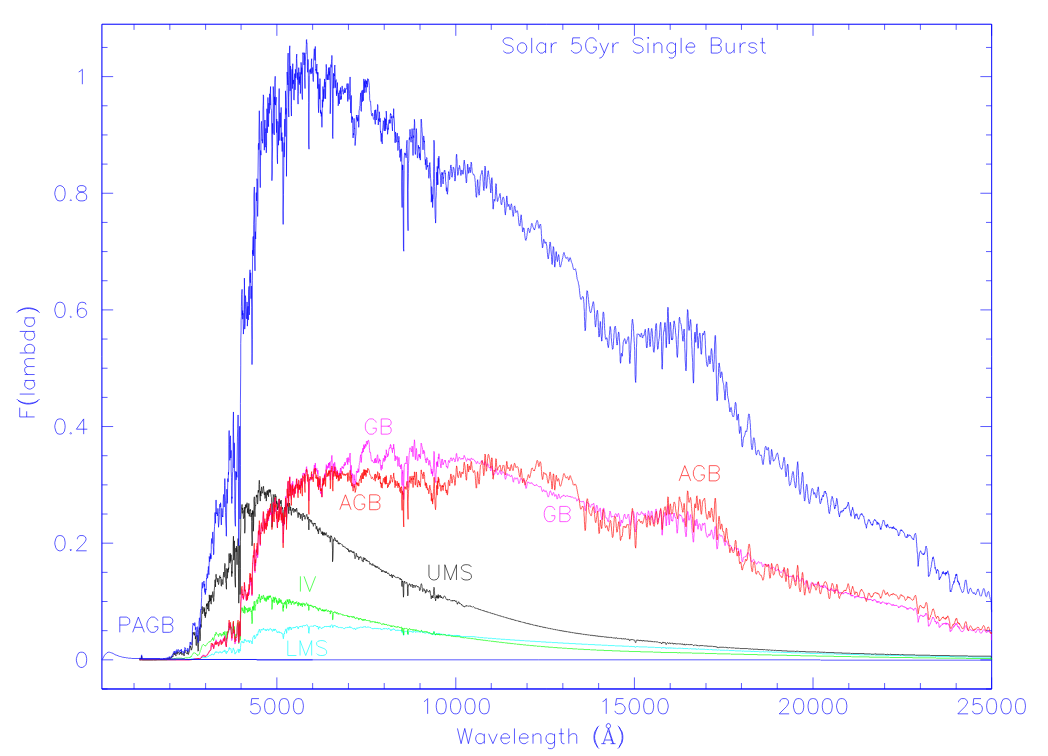

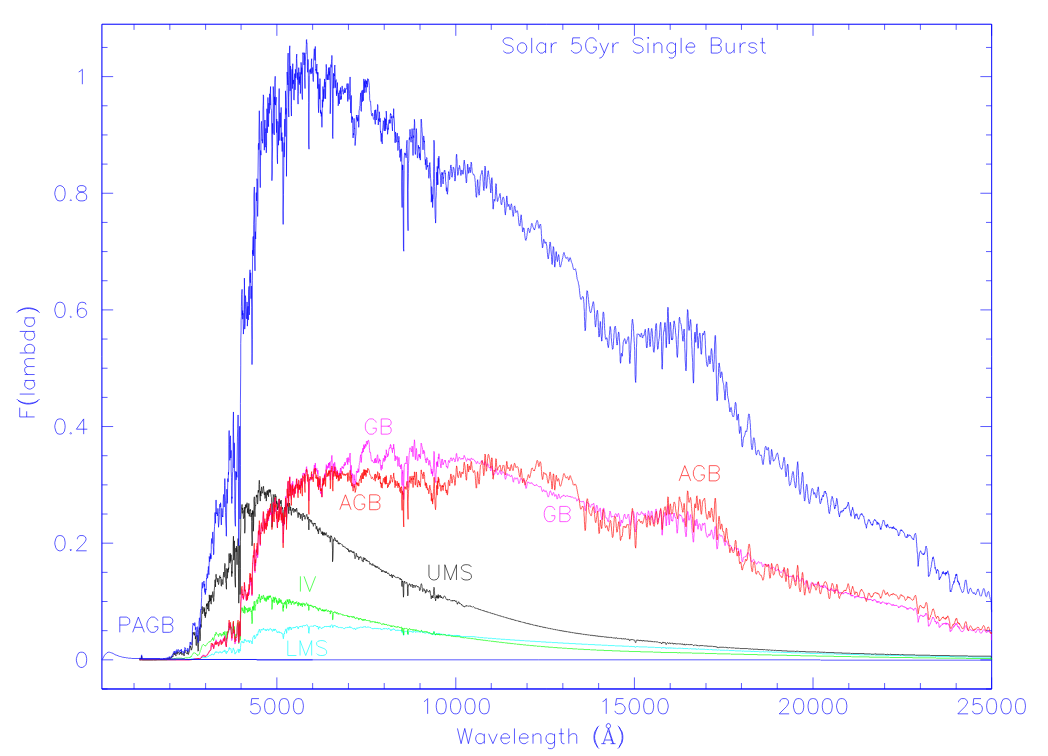

Finlator et al., AJ 120, 2615 (2000)

Figure 8 taken from

Pickles, PASP 110, 863 (1998)

The absorption lines in stellar atmospheres we see in the optical,

due to electronic transitions within atoms

and ions,

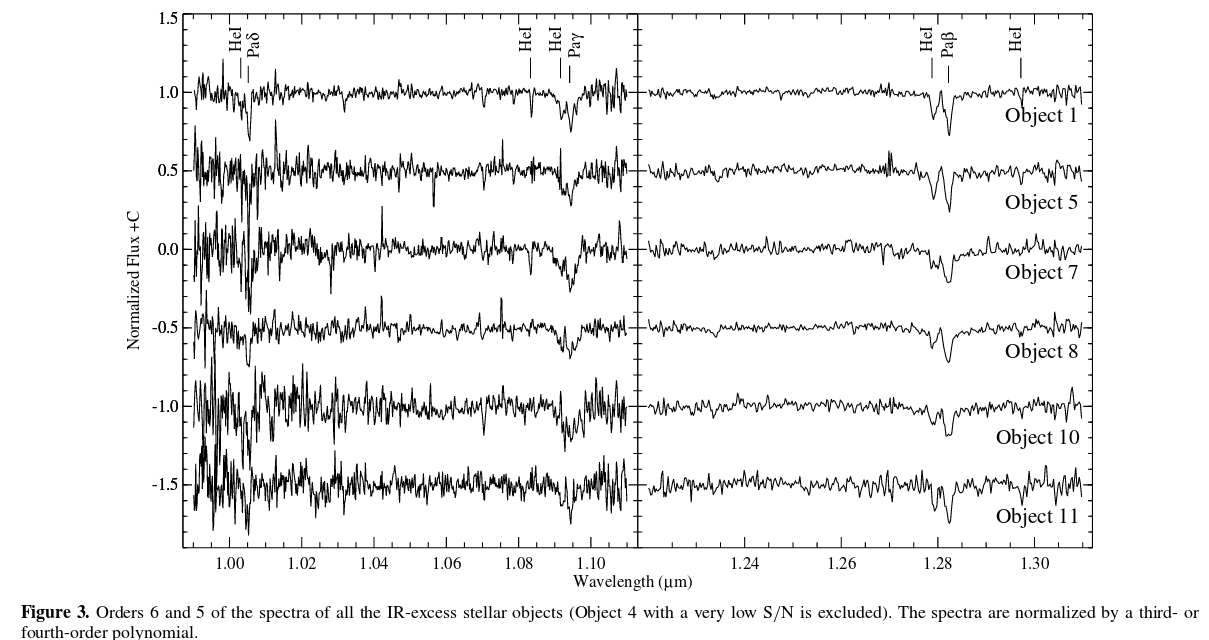

have counterparts in the near-IR.

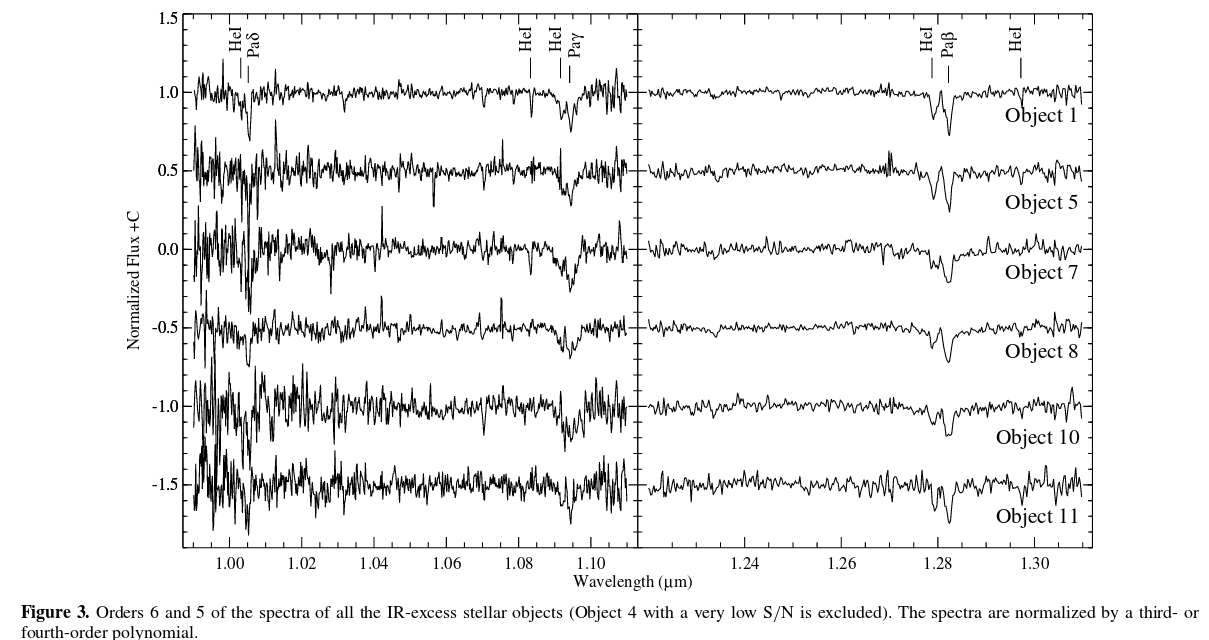

Figure 3 taken from

Kim, Koo, and Moon, ApJ 774, 5 (2013)

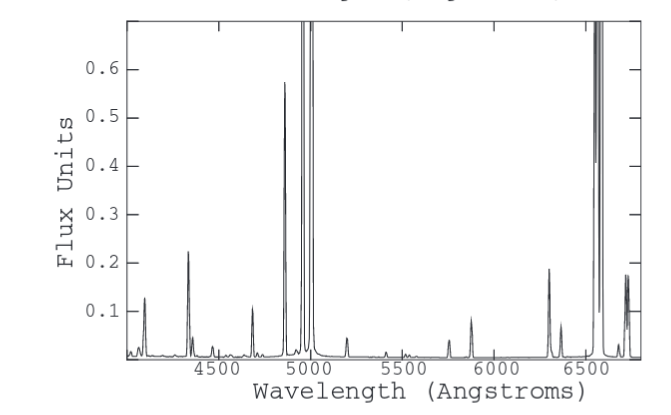

Sharp, narrow emission lines from hot gas appear in the

spectra of planetary nebula in the optical,

Figure 1 taken from

O'Dell, Henney, and Sabbadin, AJ 137, 3815 (2009)

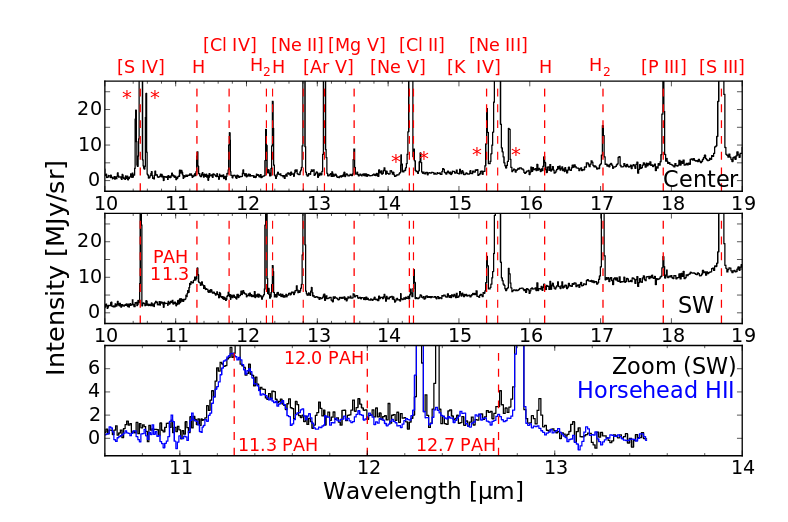

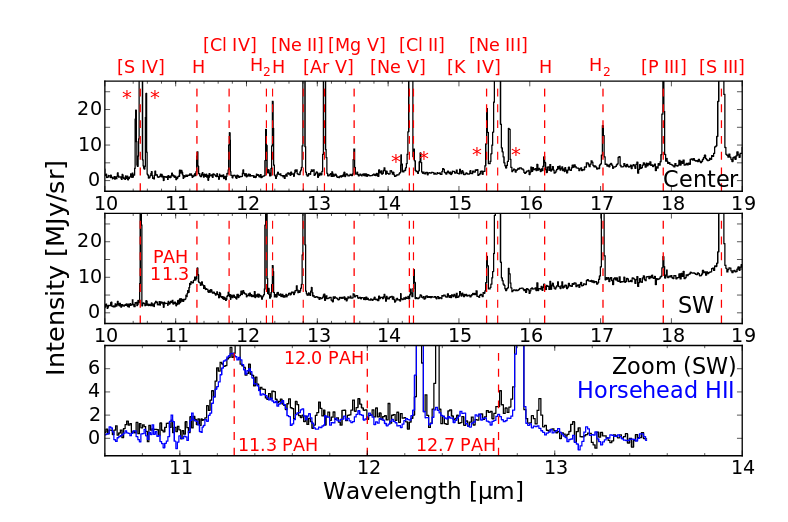

and in the IR, too:

Figure 2 taken from

Cox et al., MNRAS 456, 89 (2016)

But ... wait a moment.

The infrared spectrum shows something new and different,

which does not appear in the optical spectrum.

Q: What new type of feature appears in the IR spectrum?

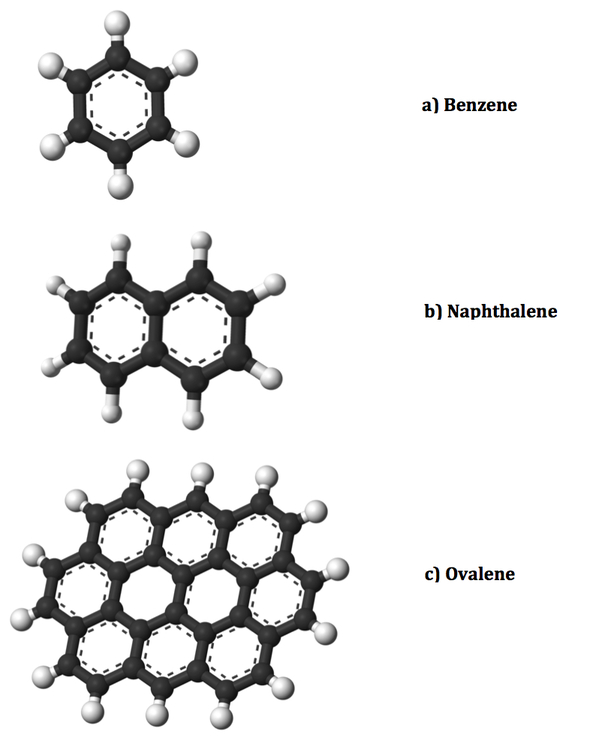

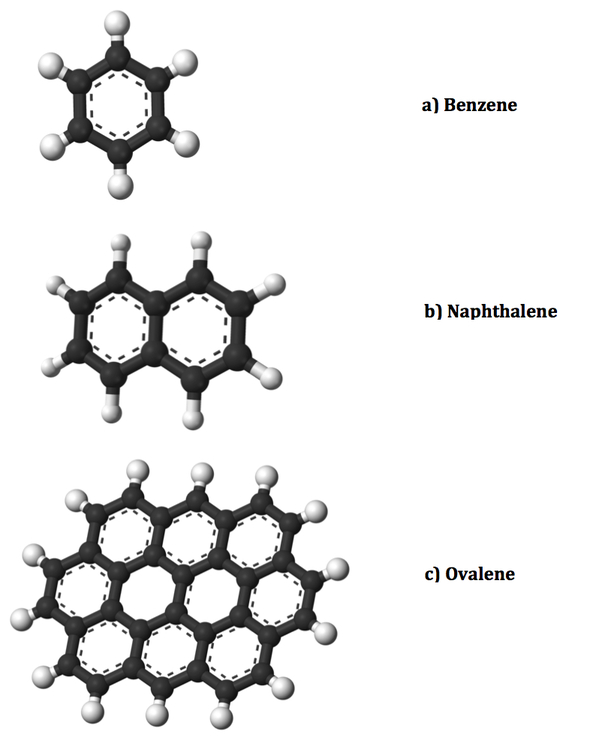

Yes, that's right: the very broad line labelled "PAH".

This radiation comes from complex molecules

called "polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons",

a few examples of which are shown below.

Figure courtesy of

Landmarks of the ISM

When atoms combine into molecules,

they gain new ways to absorb and emit photons.

For example,

the molecules may rotate or vibrate

at a range of frequencies,

or they may bend and wiggle back and forth.

Some forms of these molecular transmissions

yield broad features,

due to blends of emission from molecules with

small differences.

Others create characteristic bands

of lines in a series;

the example below shows the 2.29-micron

bandhead of CO.

Infrared spectra of stars near Sgr A* courtesy of

Eckart, Ott, and Genzel, and GCNEWS (1999)

Because these molecular transitions are typically

much lower in energy than the electronic transitions

of individual atoms and ions,

we see the radiation produced by them in the infrared.

So, looking in the infrared allows us to detect

and measure the presence of molecules,

instead of atoms.

That's new.

But that's not all.

When we look in the optical,

we see (for the most part) objects which are

hot enough to emit at visible wavelengths (stars)

or very large objects which are illuminated by

very hot objects (planets).

What we can't see are objects

which have much lower temperatures --

of hundreds Kelvin, instead of thousands.

But cool objects emit copious amounts

of infrared radiation.

One of the forms of matter

which we dominates our views in the infrared is warm dust.

Q: What make dust so prominent in infrared surveys?

Provide two important reasons.

1) dust is very _____________

2) dust is very _____________

The answer

Okay, the first part is pretty obvious:

there must be a lot of dust out there.

Our current theories of planet formation suggest that

when a proto-stellar nebula collapses,

a great deal of dust is formed very early on.

Some of it coagulates into larger particles

(rocks), which may collide and form even larger

objects (asteroids and planets),

but a great deal remains in the form of tiny particles.

But why is it important that dust is SMALL?

Well, it has something in common with the reason

why the largest insects on Earth were "only"

this big:

Image of meganeura model courtesy of

Land of the Dead

Insects, you see, don't have lungs and circulating fluid to transport

oxygen from the atmosphere into their bodies,

as we vertebrates do.

They rely largely on diffusion

to move oxygen into their cells,

and carbon dioxide out of them.

And that means that no portion of

an insect's inner body can be more

than a few centimeters (or in most cases,

a few millimeters)

from its surface.

In other words,

small objects have large ratio of surface area

to interior volume.

Since insects need this large ratio to breathe,

they can't grow very large.

What does all this have to do with infrared emission from

dust particles?

Well, let's take a bunch of matter --

iron, oxygen, hydrogen, etc. --

and form it into two piles of equal mass,

and equal density.

Each will have 1 Earth mass = 5.98 x 1024 kg

and density = 5510 kg/cubic meter.

- big particle: one spherical lump: R = 6.37 x 106 m

- small particles: spheres of radius r = 10 microns

Q: How many big particles are there?

Q: How many small particles are there?

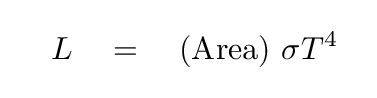

Now, suppose we set all the particles, big and small,

to the same temperature.

Let's pick T = 270 Kelvin,

which is roughly the temperature of the real Earth.

The particles will all emit blackbody radiation, with

a total luminosity of

Q: What is the luminosity of the single big sphere?

Q: What is the luminosity of the many little spheres?

The moral of the story is that

dust particles can produce LOTS of infrared!

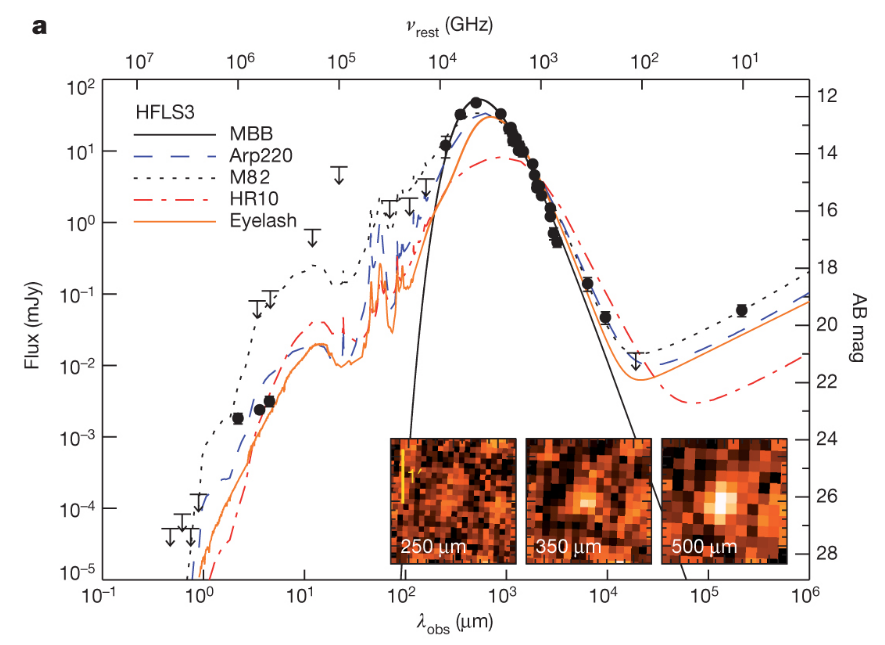

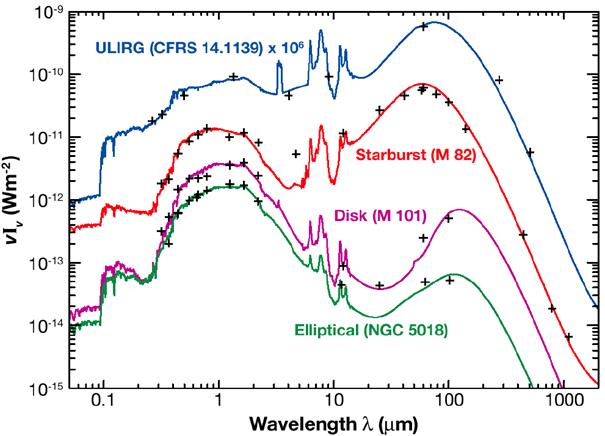

When we look at many galaxies

in the infrared, we see that their overall

luminosity is often dominated by dust.

Image 184 from

Infrared Astronomy

edited by L. Viktor Toth

Figure 2a taken from

Riechers et al., Nature 496, 329 (2013)

It might be useful to note a few numbers:

the temperatures of blackbodies which have peak

emission at some representative temperatures.

- a blackbody with peak emission at 1 micron

- a blackbody with peak emission at 10 micron

- a blackbody with peak emission at 100 micron

In summary,

infrared instruments

allow us to see an entirely new feature in the

celestial landscape --

one which is entirely invisible to optical devices!

The ability to detect dust and other cool components

of the interstellar zoo

would seem to be a strong reason to build

and use infrared telescopes ...

but it's not the only one.

In some cases,

we may be interested in plain old stars

(which certainly do emit plenty of light in the optical),

but need to look in the infrared anyway.

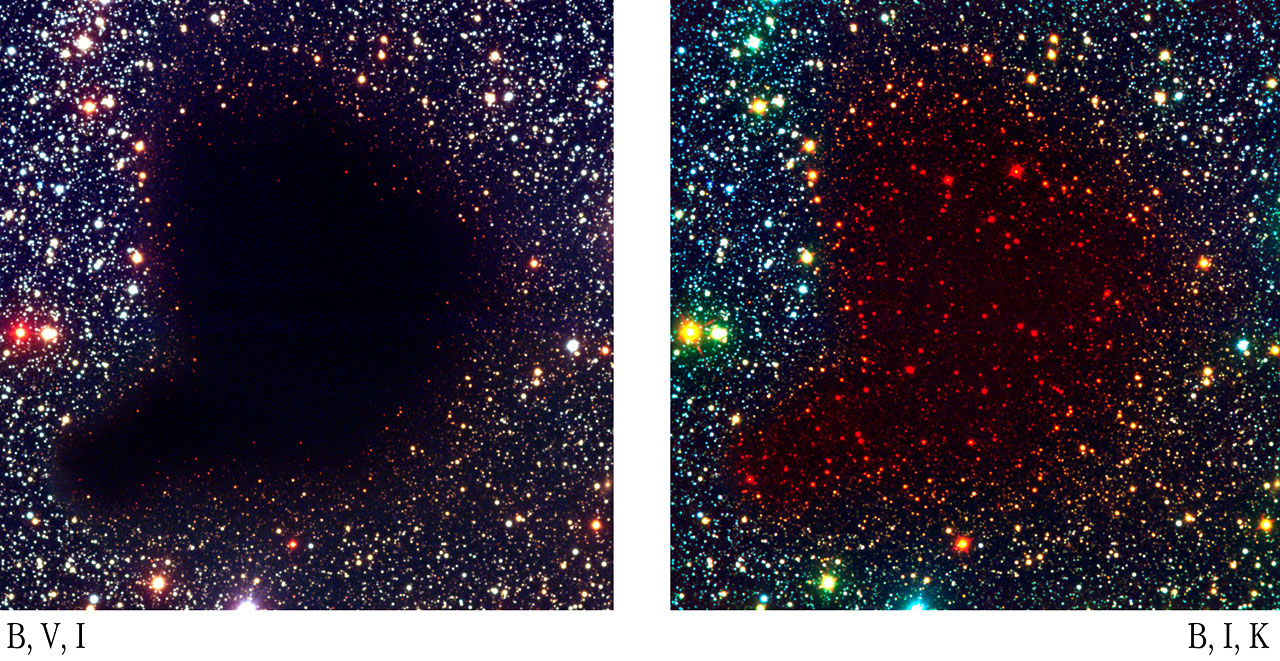

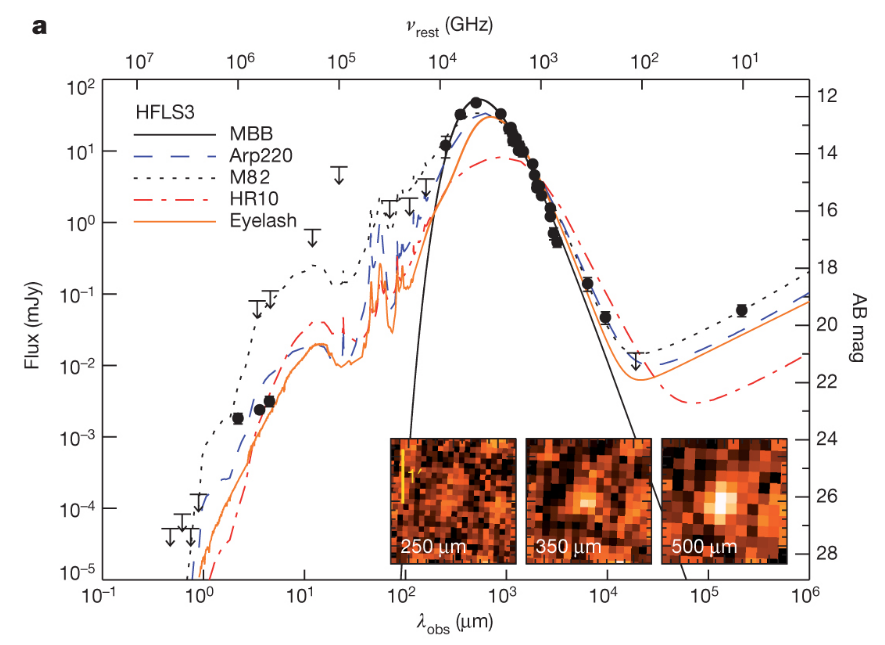

- due to extinction

-

If our targets of interest happen to lie behind

clouds of gas and dust,

the light from them may be extinguished

as it passes through the clouds.

But as

as you have already seen,

light of long wavelengths can travel through such

clouds more effectively than light of short wavelengths.

So, even if we can't detect the targets in the optical,

we may still see them in the infrared.

Image courtesy of

ESO

Image courtesy of

ESO

Q: Use the SkyView Query Form to request an image

of Sgr A* (the center of our Galaxy) taken with the "DSS2 Red" survey.

Use 600 pixels and a 1 degree field.

(my version)

Q: Use the SkyView Query Form to request an image

of Sgr A* taken with the "Wise 22 micron" survey.

Use 600 pixels and a 1 degree field.

(my version)

- due to high redshift

-

Suppose that we want to study a particular

feature in the spectrum of some glowing gas ... say,

the Hydrogen-alpha line at 6563 Angstroms.

If the stars in our study are in the Milky Way Galaxy,

then we can simply use a filter which includes

the rest wavelength: 6563 Angstroms.

Image of Orion courtesy of

APOD and

Rogelio Bernal Andreo

But if the gas lies in a galaxy which is moving away from us

at high speed, the light it emits will be shifted to

a longer wavelength. The relationship between the rest wavelength

and observed wavelength is simple, if the

recession velocity is small compared to the speed of light;

using the shorthand β = v/c,

But if the recession velocity grows to a significant fraction

of the speed of light, we need to use a somewhat more

complicated formula:

Astronomers -- particularly observational types like me --

often aren't so interested in the exact value of the

velocity of distant galaxies.

Instead, we are content to describe them by the

simple ratio of the observed and rest wavelengths,

a quantity known as redshift.

Plenty of astronomers study galaxies and quasars at

redshifts of z = 1 or higher.

The most distant galaxies we have observed

at the current time are around z = 7 or so.

Q: At what wavelength must we observe to see H-alpha

at a redshift of z = 1?

Q: At what wavelength must we observe to see H-alpha

at a redshift of z = 7?

In fact, astronomers interested in distant galaxies often

pay more attention to the Lyman-alpha line of hydrogen,

which is produced when an electron jumps down from the n=2

state to the ground n=1 energy level.

Q: What is the energy of a Lyman-alpha photon in eV?

Q: What is the rest wavelength of a Lyman-alpha photon?

Q: What region of the electromagnetic spectrum is that?

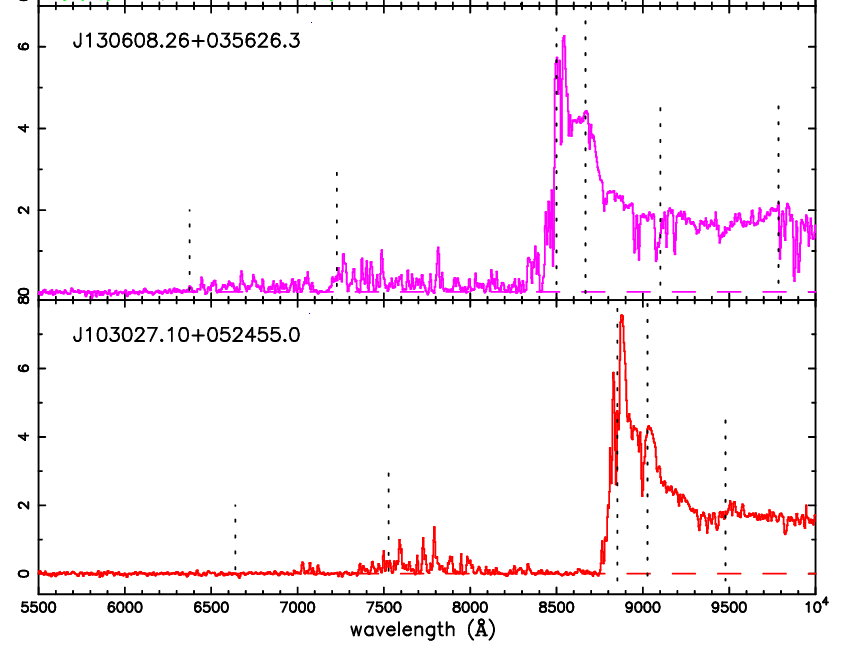

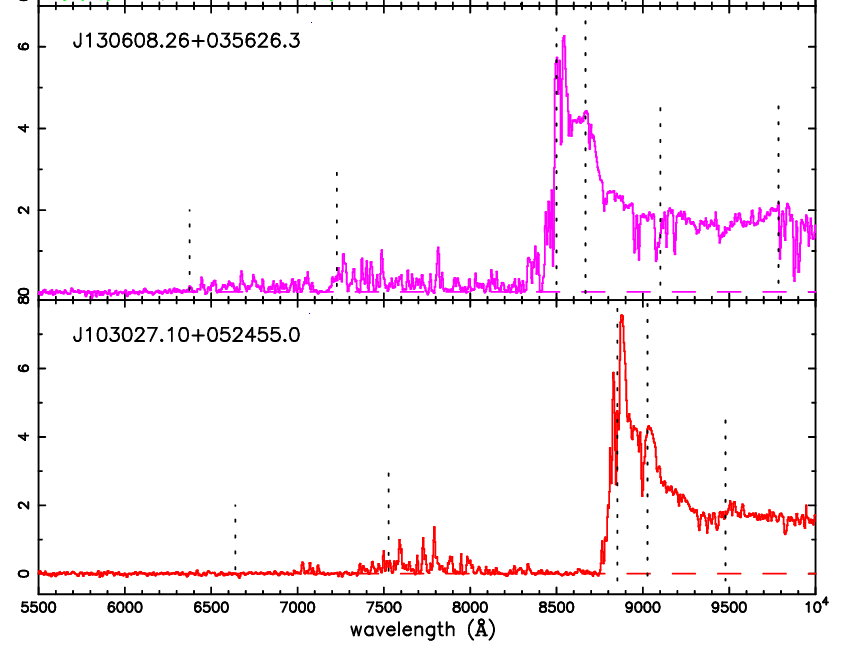

Below are a couple of spectra of some distant galaxies

with strong Lyman-alpha emission lines.

Can you figure out their redshifts?

Figure 1, slightly modified, from

Becker et al., AJ 122, 2850 (2001)

The answers

But suppose that we want to discover the very earliest

galaxies, back when they were first forming.

They might appear as early as z=10 or z=12.

Q: At what wavelength would Lyman-alpha appear in a galaxy

at z = 10?

Q: What region of the electromagnetic spectrum is that?

So, yes, the infrared is vital for studying

galaxies at high redshift.

For more information

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.