Thanks to Ron Markham for the animation.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

You can read notes from a talk one year ago ...

On March 6, 2009, NASA launched the Kepler satellite which is designed to find hundreds of planets around other stars (in addition to a good deal of other science). How will it look for those planets? Just what is inside the Kepler mission? And what has it found so far?

Let's find out.

The transit method is pretty easy to explain: if a planet's orbit around its star happens to cause the planet to pass in front of the star from our point of view, then the planet will block a little bit of the Sun's light for a brief time -- a few hours to a day or so.

Thanks to Ron Markham

for the animation.

Of course, this only works if the orbital plane of the planet is tilted just right. It's also a somewhat delicate measurement to make, since most planets are so much smaller than their stars that the dip in brightness is almost always less than one percent. See for yourself in this picture of a genuine transit, as Venus passes in front of our Sun.

However, if one makes careful measurements and uses the right sort of analysis, one can detect these little dips with relatively small telescopes. The first transit was measured by this little telescope:

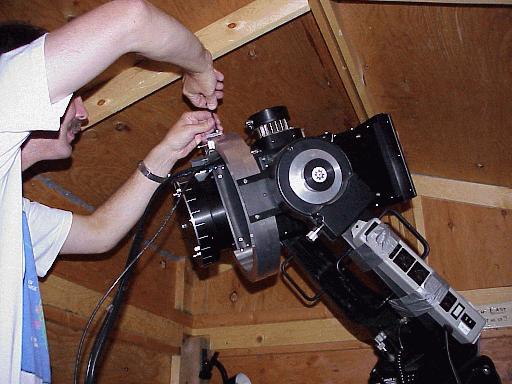

Here in Rochester, the RIT Observatory's 12-inch telescope and SBIG ST-8E CCD camera acquired this light curve of the system called TrES-3

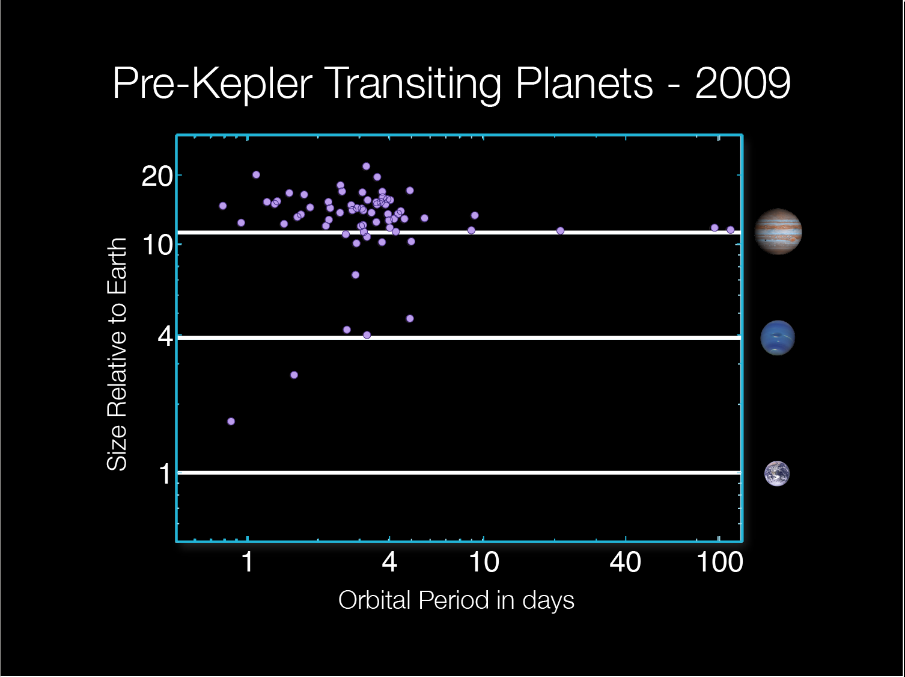

Before Kepler started to look for planets via this transit technique, astronomers had already discovered quite a few using ground-based telescopes. We'll come back to see how Kepler's work compares to this set of planets a little later ....

How big is the telescope in Kepler? (Ouch, that sounds rather painful. Let me try writing that again)

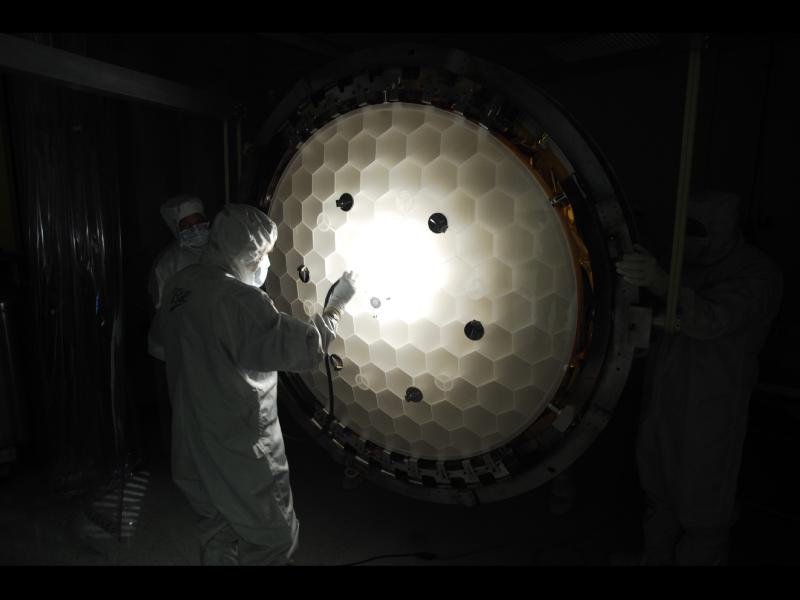

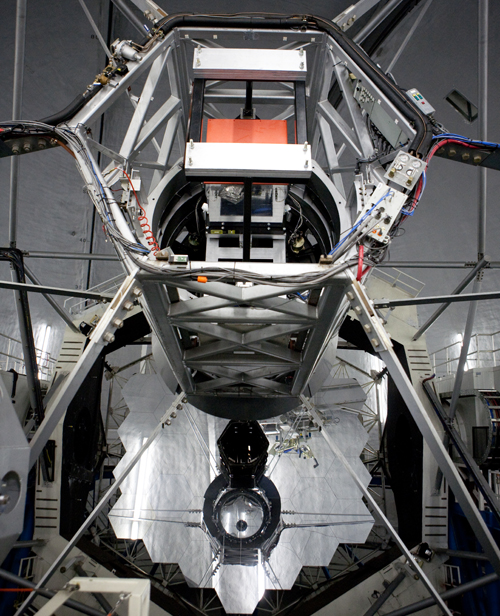

How big is the telescope inside the Kepler satellite? Pretty big: the primary mirror is 1.4 meters in diameter, but it sits behind a clear aperture of only 0.95 meters. So Kepler's aperture is smaller than that of HST, but much larger than those in the telescopes in the MOST (15 cm) or COROT (30 cm) satellites.

The telescope sits inside a satellite which is the size of a schoolbus.

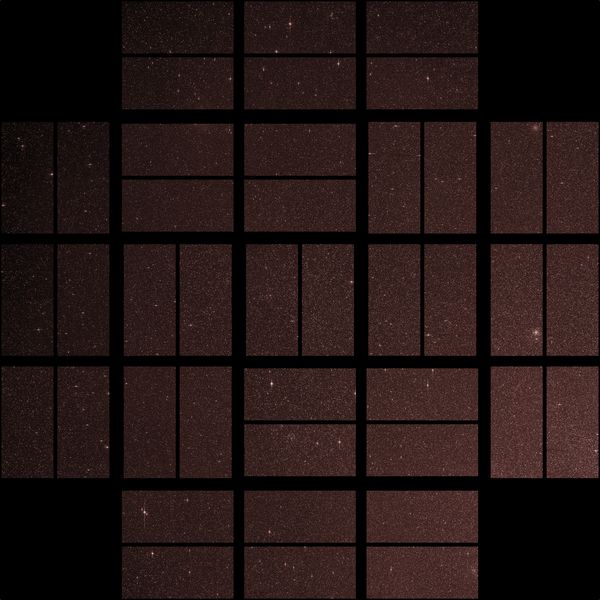

Notice the curvature in the focal plane. Kepler is designed to cover a wide field -- about 16 degrees in diameter -- and in order to keep the images sharp near the edges, one has to move the detectors to follow the curvature.

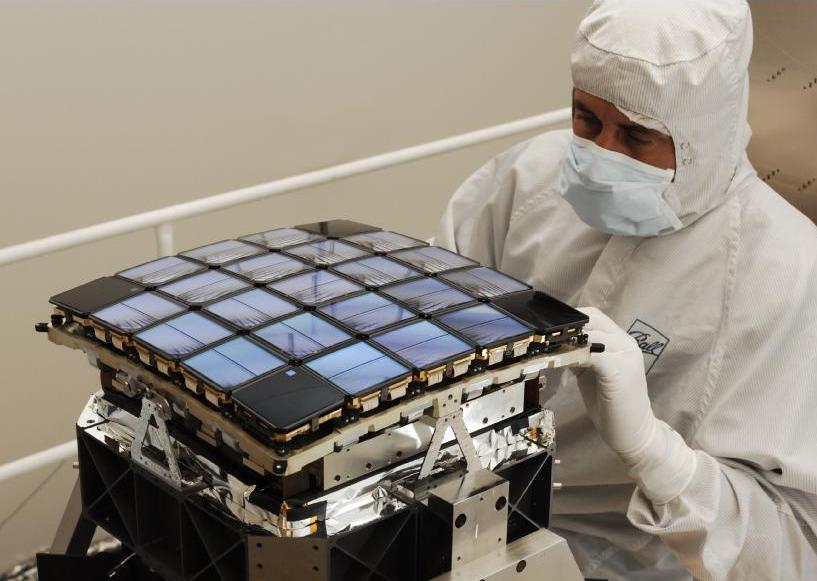

That looks like a lot of detectors .... and it is. In fact, there are

42 CCD chips, each of which is

50mm x 25mm

2200 x 1024 pixels

Can you guess how much memory it would take

to store a single "image" from this camera?

Answer: 42 chips * (2200x1024 pixels/chip)

* (2 bytes per pixel)

= 190 MegaBytes

Each of the shiny square regions in the picture above is actually 2 CCD chips. You can count them more easily in this picture, which is one of the first-light images returned from the spacecraft in April, 2009.

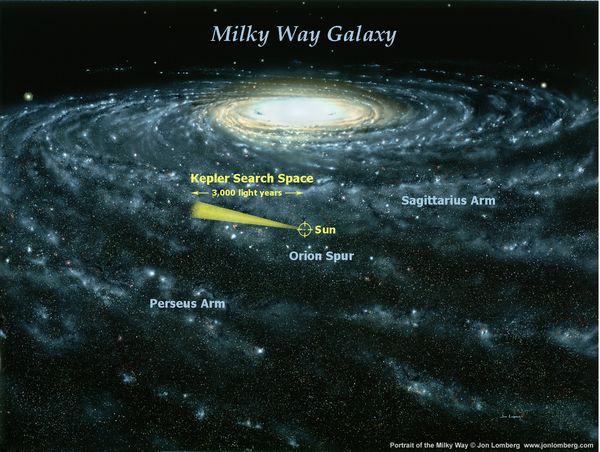

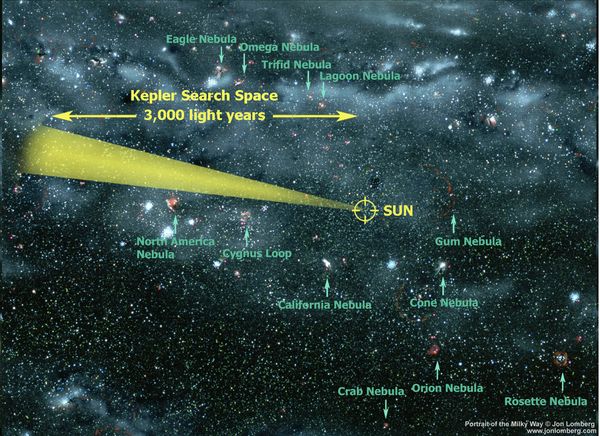

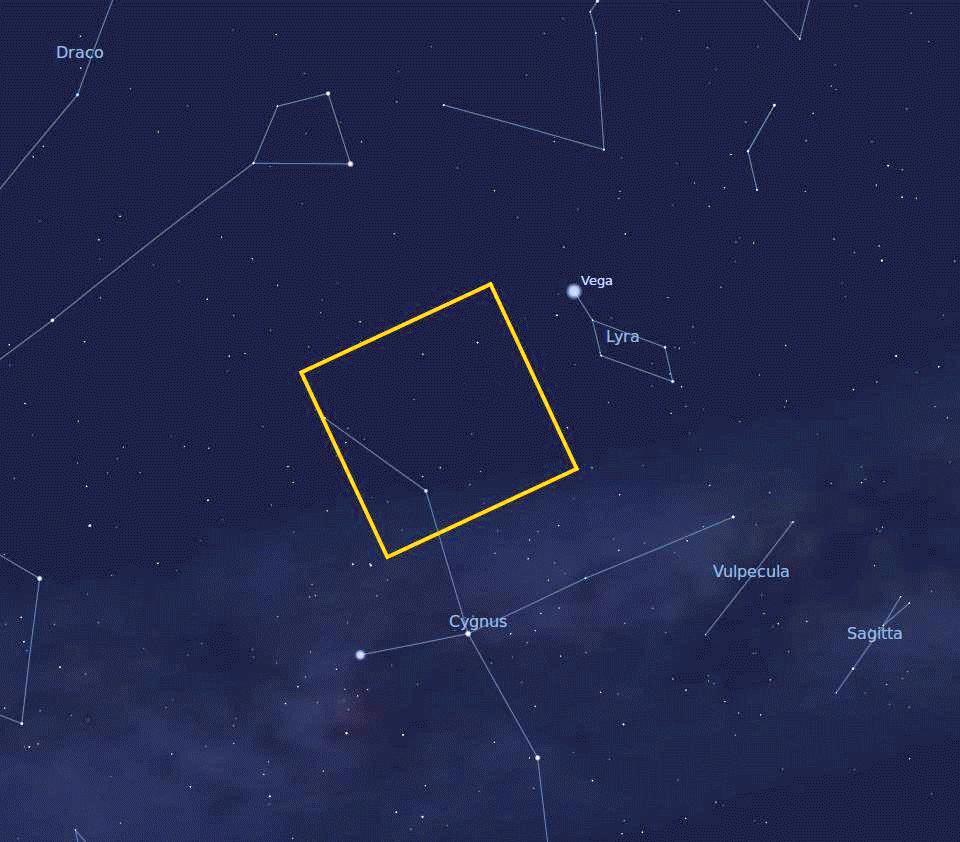

After doing the math, the planners have chosen a field in the Milky Way between Cygnus and Lyra. The field is centered at RA = 19:22:40 and Dec = +44:30:00, about 15 degrees away from the plane of the Milky Way. Only a single star brighter than sixth magnitude lies in this region, and only 12 stars brighter than sixth magnitude, so little of the detectors' area will be lost to bleed trails and saturation. In this region, a star like the Sun would reach V=12 at a distance of 270 pc, and it is possible (as we will see below) that Kepler might detect planets as small as the Earth around stars at or a bit beyond this distance. There are many tens of thousands of stars which lie within the dynamic range of Kepler: from V=7 to V=17.

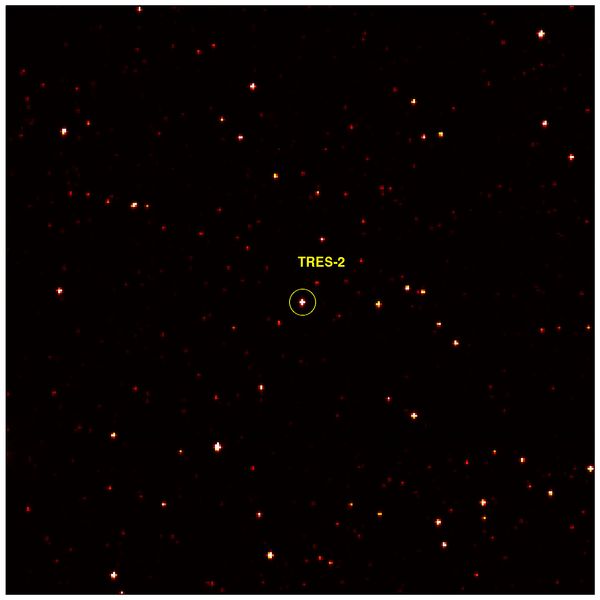

Note that Kepler's spatial resolution is not very fine: each pixel spans about 4 arcseconds. You can see the blockiness in this picture of the star TrES-2 . In addition, the telescope's focus is set so that stars are slightly out-of-focus, which spreads their light out across more pixels and helps prevent saturation.

However, the Kepler team has determined that even if a star saturates a CCD detector, they can still measure its brightness precisely. Stars which are up to 50 times brighter than the saturation point will cause charge to flow into neighboring pixels, but in a repeatable manner. The pipeline used to measure stellar brightness can handle these heavily-saturated stars under most conditions, allowing Kepler to study stars as bright as seventh magnitude.

In ordinary operation, Kepler looks at the same field over and over and over and over many times; the length of the mission is planned to be at least 3.5 years. The camera takes exposures in the following manner:

What's with the "groups"? Well, here's the problem: each individual exposure contains about 190 Megabytes of raw data, over just 6 seconds. If the satellite tried to transmit all that raw data back to Earth before the next picture was taken, it would to transmit at a rate of about 32 MBytes per second, to a ground station which was always listening. Alas, the actual performance of the transmitter is only about 0.5 MBytes per second (in the Ka band), AND the ground station only listens once a month. So, there's no way for Kepler to send us all its raw data.

Therefore, scientists have studied the field of view in advance and made a catalog of the stars which can be measured precisely and which are likely to be of interest. The astronomers on the team can choose two sets of stars:

In this way, the spacecraft can store the pixel-by-pixel data of a set of selected stars and discard the full-sized raw images. Only the data for the selected regions needs to be transmitted, and that's a tiny, tiny fraction of the volume of the raw data.

Very, very precisely. Much more precisely than any instrument can do from the ground, and (I think) more precisely than any of the existing space satellites, though MOST might give it a run for its money.

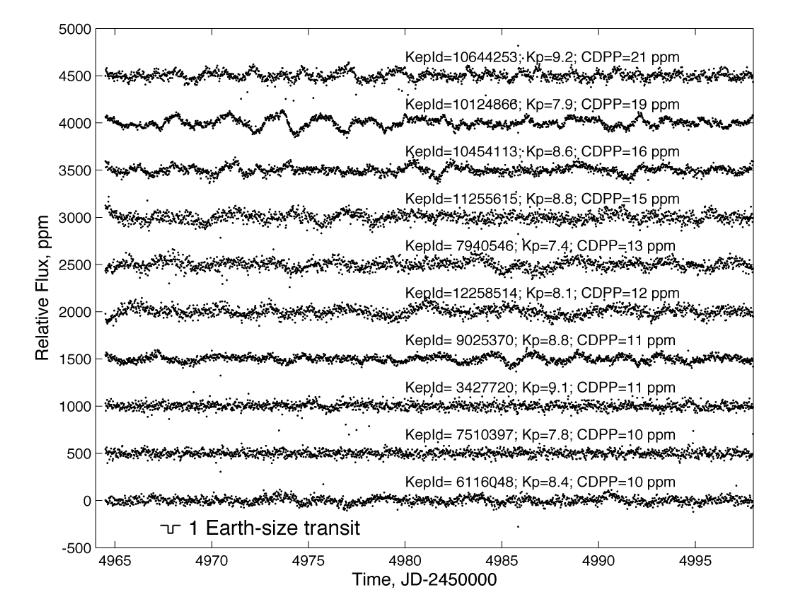

The first results from Kepler were announced at the recent AAS meeting in January, 2010. Here are some light curves from some of the brightest stars in the field. The units of time (horizontal axis) are days, and the units of flux (vertical axis) are parts per million.

For comparison, here's what the light curve of a constant star measured by one of the best ground-based telescopes might look like: it has a scatter of only 0.1 percent = 0.001 magnitude. I've only reached about 0.003 magnitudes at best, myself.

Yes, it has. Some of the planets announced in the most recent data release are not only roughly the size of the Earth, but are even at distances from their host stars that are likely to produce roughly Earth-like temperatures.

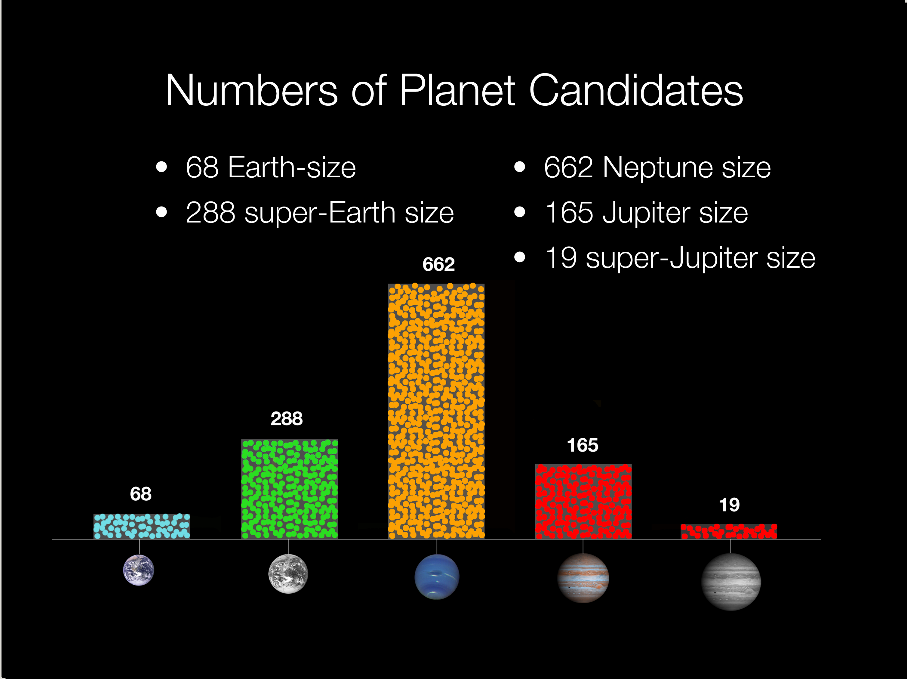

The most recent official update from Kepler (Feb 2, 2011) announces

What's the difference between a "confirmed planet" and a "planet candidate"?

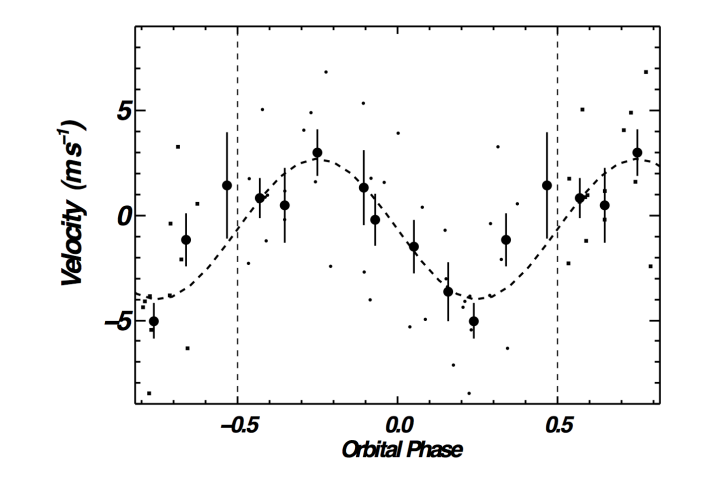

If a planet is really orbiting a star, the gravitational pull of the planet will pull the star towards us and away from us in a cycle which exactly matches the spacing between the dips in light Kepler sees. We can detect the motion of the star by measuring precisely the wavelength of light it emits. Click on the picture below to see the wobble in action.

Why are there so few confirmed planets, and so many planet candidates? The problem is that, although even a small telescope can detect the transit of a planet, it requires a much larger telescope to gather enough starlight to determine the tiny shifts in wavelength due to the star's motion.

Figure taken from

Batalha et al., ApJ 729, 27 (2011)

Image

courtesy W. M. Keck Observatory.

Let's take a look first at the confirmed planets discovered so far by Kepler. Note the sizes.

Most of the planet candidates are also pretty big -- much larger than Earth.

There's a reason that the first planets to be announced are so big.

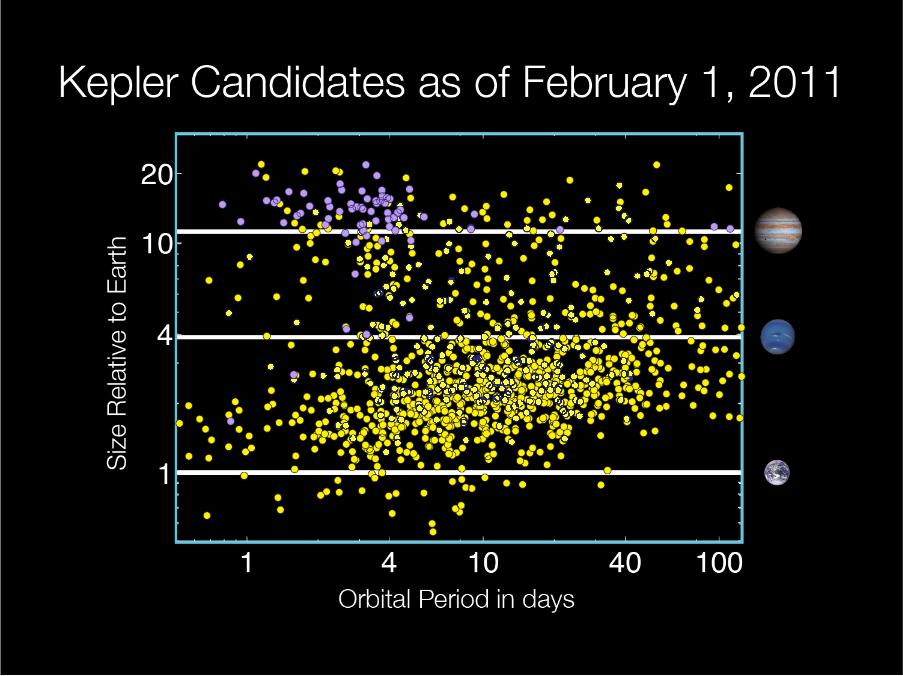

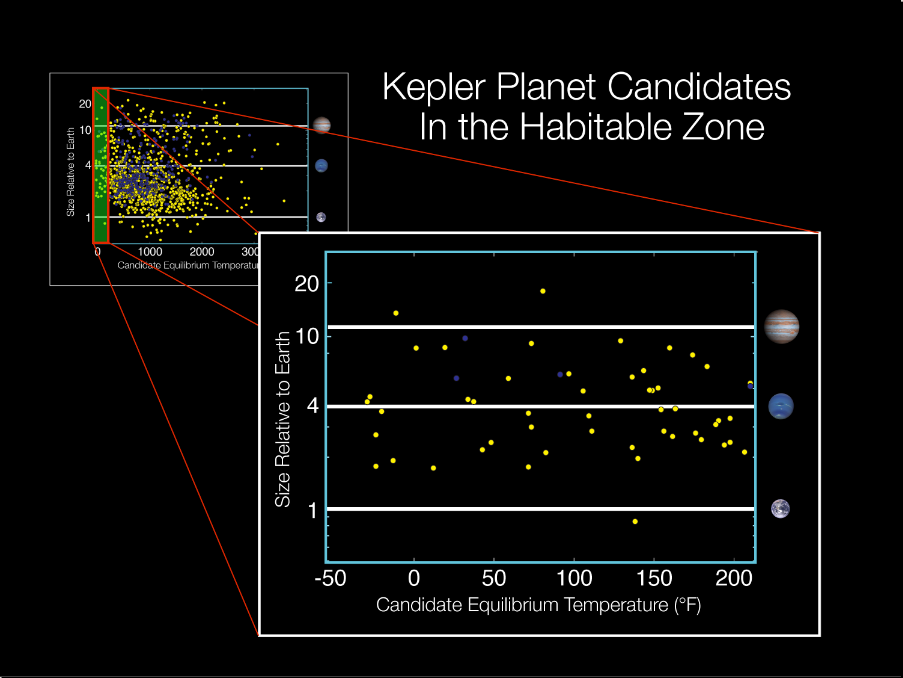

The Kepler satellite has performed as advertised: it has greatly increased the number of known transiting planets. The figure below shows the previously known planets in purple, and Kepler's candidates in yellow.

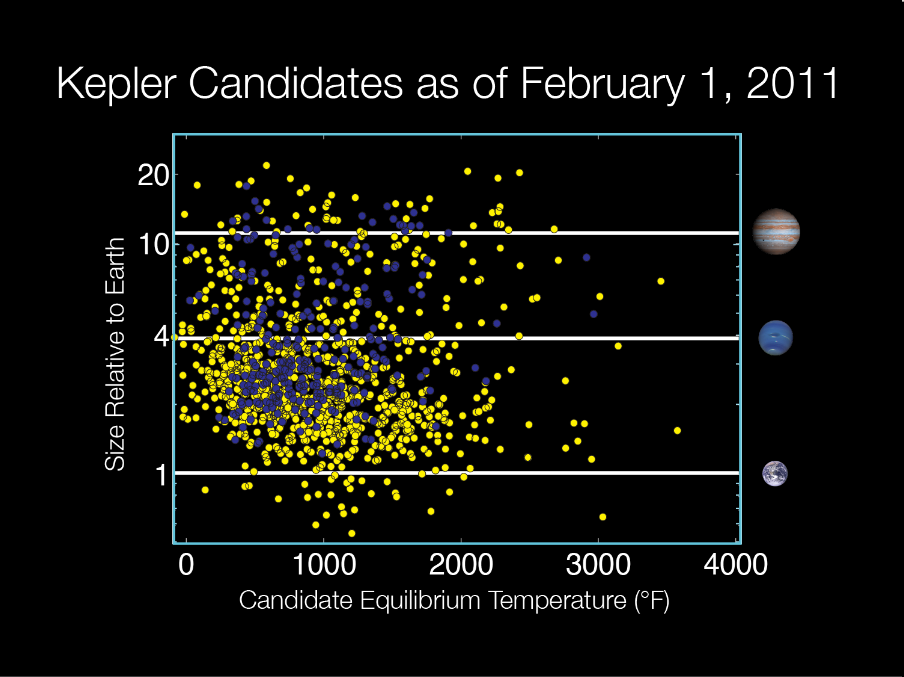

Now, most of these planets are not places you'd want to live: they are way too hot.

The planets are HOT because the easiest planets to find are those which will make many dips over the course of one year; that way, you can be sure that the dips are due to an orbiting planet, and not due to some error in the detector, or some starspot rotating across the disk of a star. If you require a planet to complete at least 3 (or 5 or 7) orbits within around 360 days, then the orbital period must be at most 120 (or 90 or 52) days. In other words, the early results have a bias towards planets with SHORT PERIODS. That means that the planets must be very close to their stars.

And planets which are close to their stars will be HOT.

Still, because Kepler has found so many candidates, a few of them do happen to orbit far enough from their host stars to yield a reasonable temperature at the surface (assuming that the atmosphere doesn't play a large role). There are a few tens of planets within the estimated "habitable zone". One of them is a pretty nice size, too!

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.