Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

The earliest and simplest telescopes are refractors. They consist of a long, narrow tube with a lens at the front end. Light which passes through the lens is bent, so that initially parallel rays meet near the bottom of the tube.

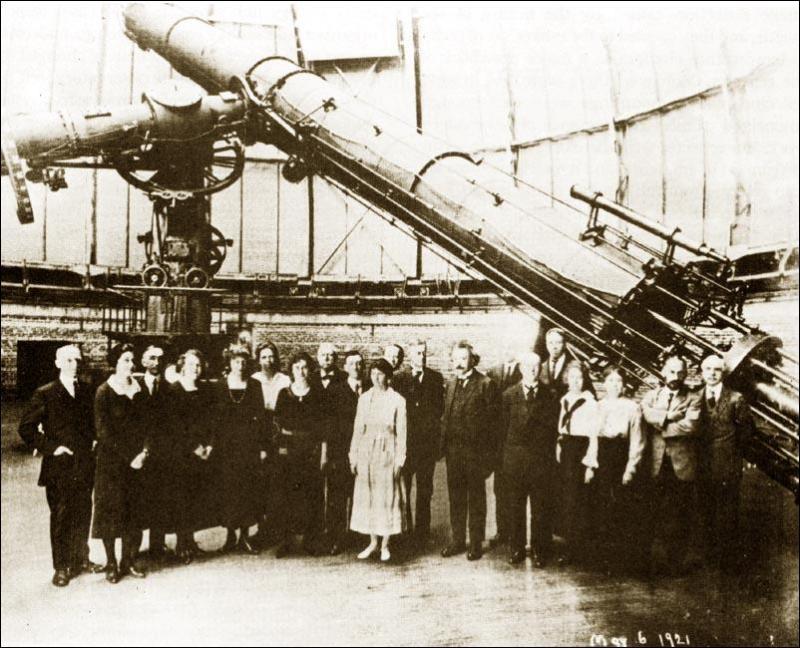

Refractors are easy to make and, when small, relatively inexpensive. Large telescopes of this sort become unwieldy. The largest refractor ever put to practical use is the Yerkes 40-inch instrument; its aperture (front lens) is 40 inches in diameter. The tube is a bit longer ...

There are several drawbacks to this design:

Isaac Newton realized that mirrors would solve the second problem: they can bring light of ALL wavelengths to a common focus. He designed a telescope which used mirrors to reflect light; hence, this type is called a reflector.

The mirror in a reflector can be supported not only around the edges, but also all over the back surface. That means that very large mirrors can be placed into telescopes. The Subaru Telescope has a primary mirror over 8 meters in diameter.

Why build large telescopes? It's not to magnify objects -- the Earth's atmosphere blurs everything to a minimum resolution of about 1 arcsecond. In order to see really fine detail in the optical, you have to move your telescope above the atmosphere:

The real reason astronomers want big telescopes is to detect fainter and fainter objects. The faintest object visible in a telescope depends on the amount of light the telescope can gather ... which in turn depends on its collecting area:

2

area = pi * (radius)

Note that the collecting area increases as the square

of the radius (or diameter).

Q: The pupil in your eye has a diameter of about 5 mm.

The little telescope at the front of the class has a

diameter of about 4.25 inches.

Q1: What is the ratio of collecting area of the telescope

to collecting area of the eye?

Q2: How many times fainter are the faintest objects you can see

in the telescope, compared to the faintest object you can

see with your naked eye?

Q3: If the unaided eye can see stars of mag m = 5,

what is the magnitude of the faintest stars visible

through this telescope?

At some point, however, even though you can support your big mirror across its entire back surface, the mirror becomes so big and so heavy that it starts to sag. Even worse, as you move your telescope to point to different regions of the sky, your mirror will sag in different ways. The mirror will no longer bring all the light rays to a single focus. Our current technology has just about reached that point with mirrors of diameter 8 meters.

What can you do if you want to see even fainter objects?

Answer: use an array of smaller mirrors.

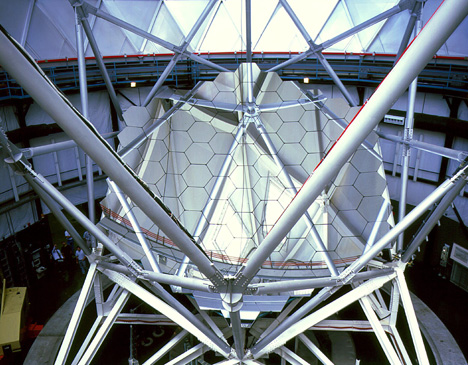

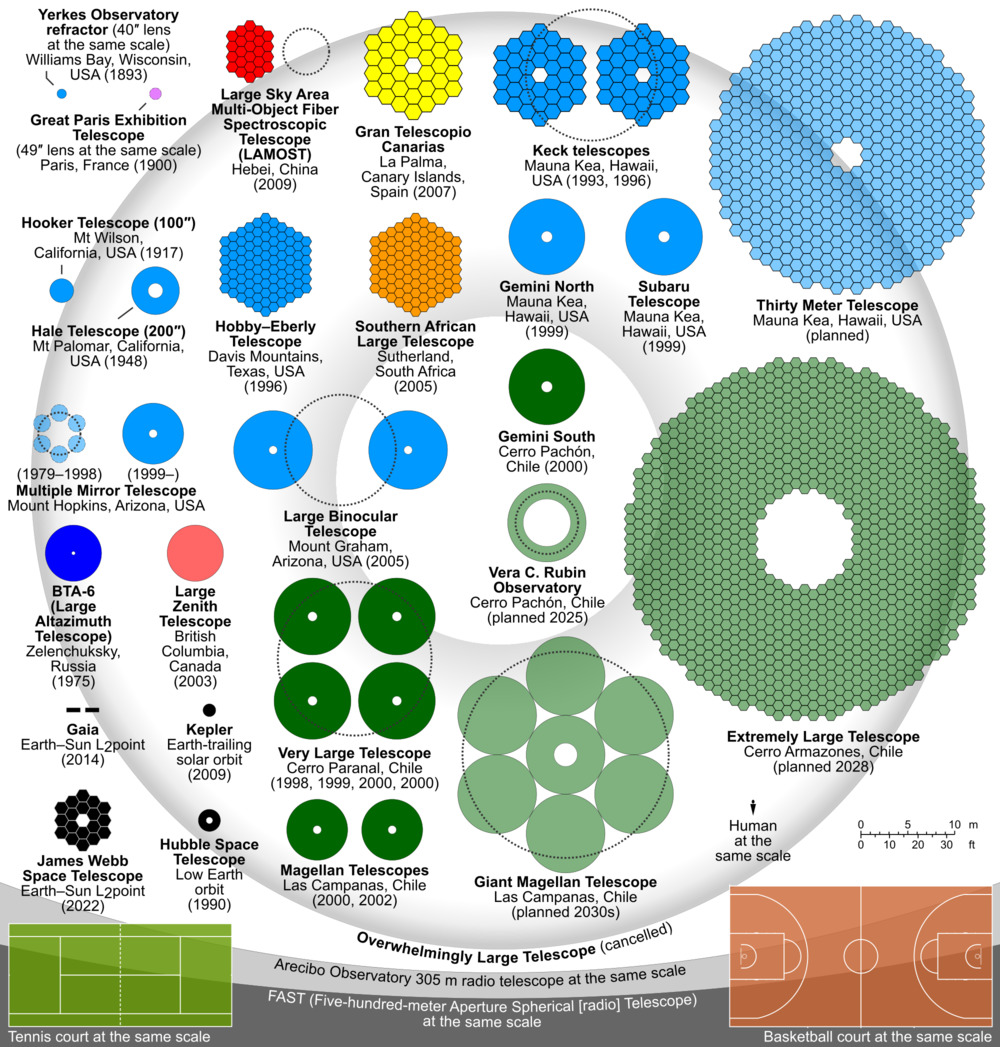

The Keck Telescopes:

The Hobby-Ebberly Telescope:

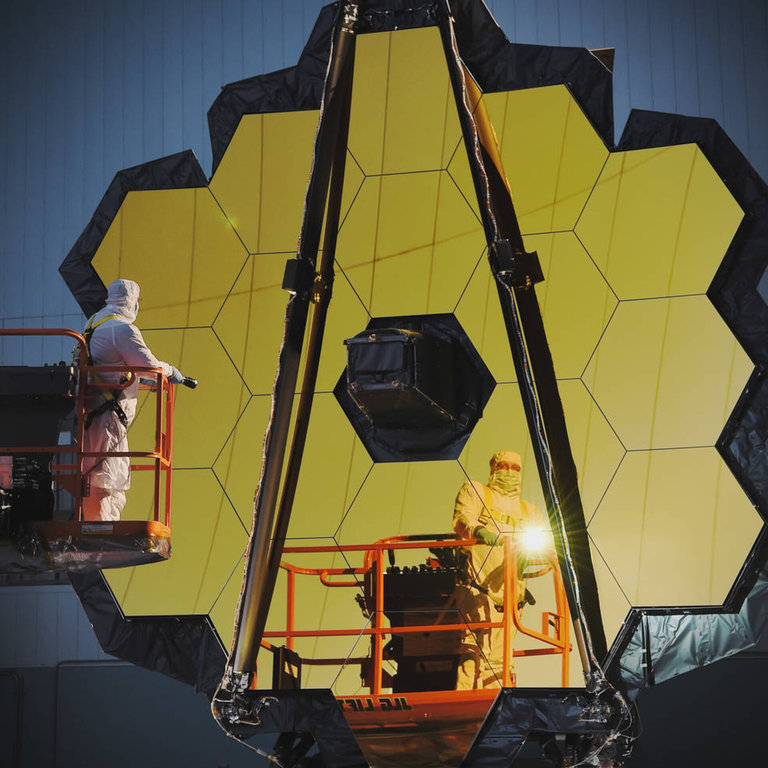

The James Webb Space Telescope:

Image courtesy of

European Space Agency

The Keck Telescope has a diameter of about 10 m. Your eye

has a diameter of about 0.005 m, and can see stars of magnitude 5

by itself.

Q: If you were to look through the Keck Telescope with your eye,

how faint a star could you detect?

Q: How faint are the faintest stars actually measured by the

Keck Telescope? (do a quick search)

Q: Can you explain the difference?

You've undoubtedly heard about the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which started operations in 2022. One can find frequent press releases describing the latest discoveries it has made. But in just a year or two or three, (at least) two other big optical telescopes will join the party -- both of which are reflectors. What do you know about them?

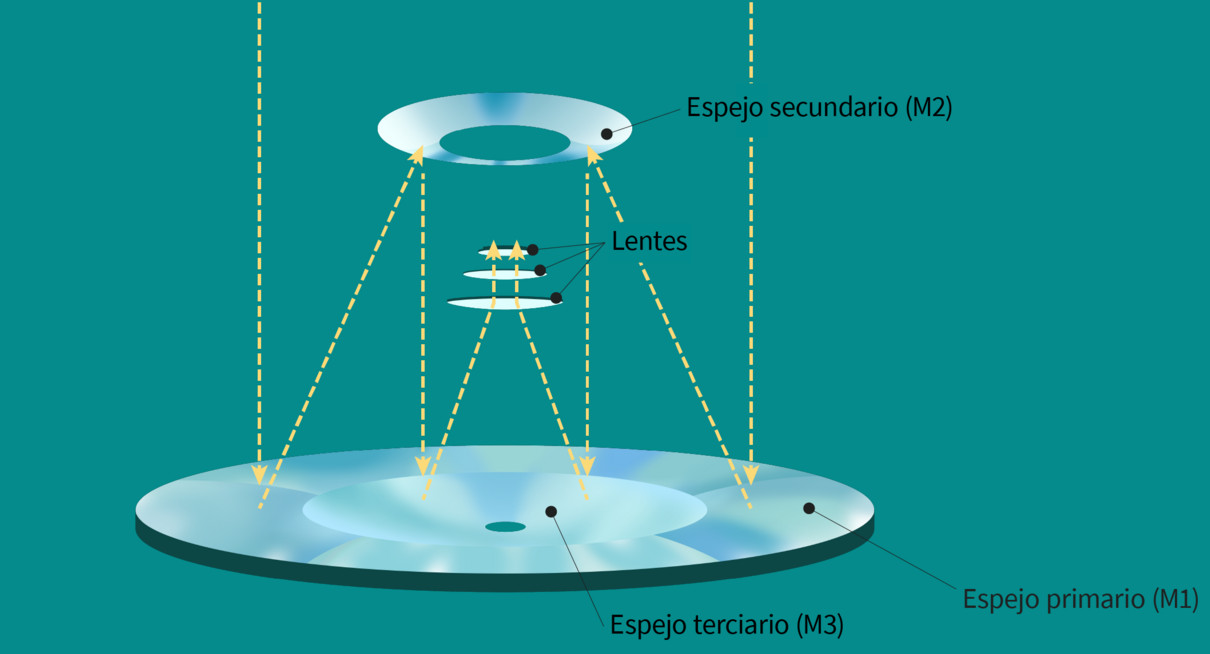

The basic idea is to design a telescope which

The design calls for a primary mirror with a very large central hole, and well as crazy secondary and tertiary mirrors, and a set of strong lenses to correct the images across the wide field.

Image courtesy of

RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/DOE/NSF/AURA

The diameter of the primary is 8.4 meters, that of the secondary 3.4 meters, and that of the tertiary -- which sits inside the primary -- a whopping 5.0 meters. Thanks to this original optical design, it will be able to provide very sharp images over an area about 3.5 degrees in diameter. A very large mosaic camera has been built to take advantage of this field: it has 189 main CCDs and a total of about 3.2 gigapixels.

Image courtesy of

Rubin Observatory/NSF/AURA

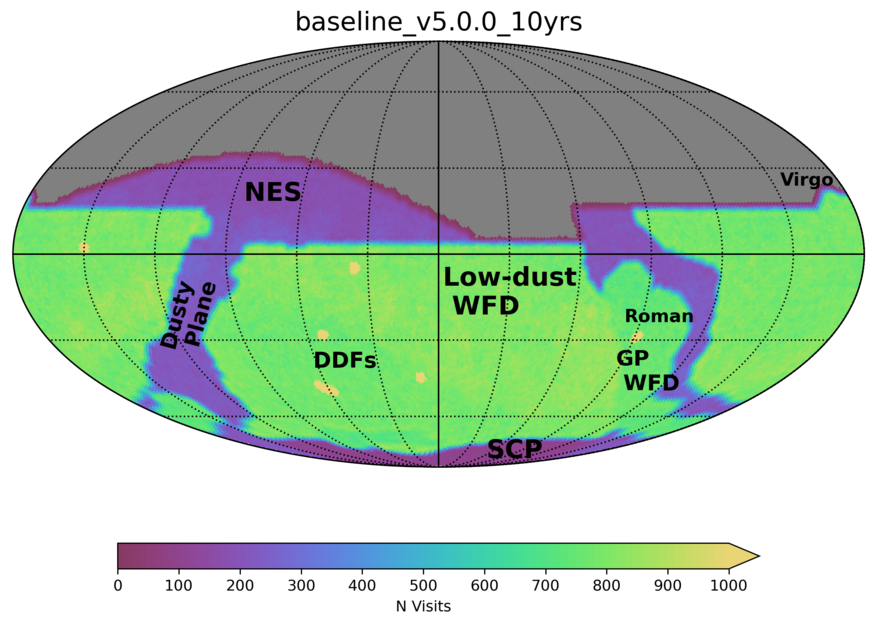

The plan is for LSST to scan the entire night-time sky visible from its location in Chile (latitude -30 degrees) roughly every three nights, with additional observing plans as well. Over a 10-year span, it will accumulate many, many images of large regions of the sky (allowing it to co-add the data and reach very faint limits).

Image courtesy of

LSST

Over the next decade or two, astronomers will have access to several new ground-based telescopes which are larger than any in use currently, and considerably larger than any instruments likely to be put in space during our lifetimes. How will these new, big telescopes improve our ability to study exoplanets?

Let's start by comparing three of the biggest projects.

| Property | ELT | GMT | TMT |

| Operator | European Southern Observatory | Aus, Brazil, Chile, Israel, S. Korea, Taiwan, US | Canada, Japan, India (US) |

| Diameter (m) | 39 | 25 | 30 |

| Collecting area (sq.m.) | 978 | 368 | 655 |

| Location | Atacama Plateau, Chile | Atacama Plateau, Chile | Mauna Kea, Hawaii |

| Altitude (m) | 3046 | 2516 | 4050 |

| Expected start date | 2028 | early 2030s | late 2030s ?? |

In a rather surprising twist, it appears that the largest of the three may be the first one to be completed ...

Figure courtesy of

Cmglee and Wikimedia

... so let's focus on the ELT.

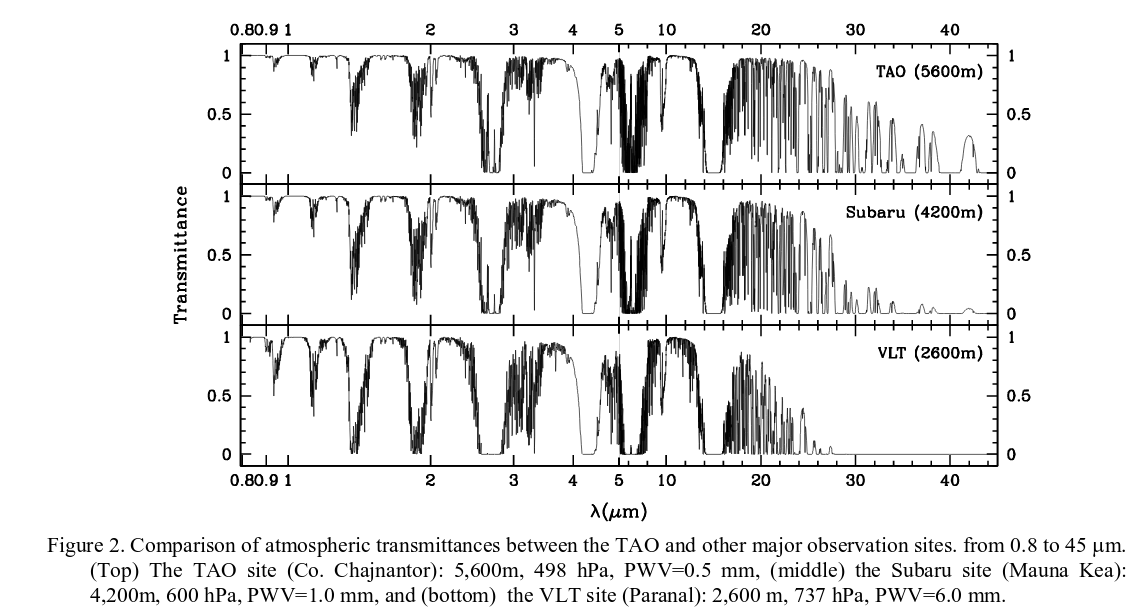

First, let's get the Bad News out of the way: because these instruments must look through the Earth's atmosphere, they are limited to studying only a portion of the near-infrared spectrum.

Figure 2 taken from

Yoshii et al., SPIE 2010

Large sections of the spectrum between 1 and 5 microns are wiped out by lines of (mostly) water vapor, and all wavelengths longer than about 12 or 15 microns are, for practical purposes, impossible to view. There is a window, the "N band", around 8-12 microns, which might be available.

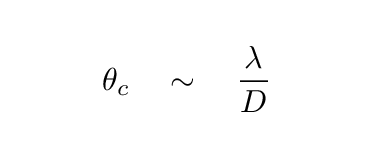

But what about the Good News? This telescope is big, which opens up new possibilities in two different ways.

So, clearly, larger telescopes have higher spatial resolution than small ones. The largest current telescopes are roughly 10 meters in diameter, and a lot of work is done by slightly smaller instruments of diameter 5 or 6 meters. The big new generation of telescopes, with diameters of 25 to 40 meters, will lead to increases in spatial resolution by factors of 3 to 8.

(Yes, of course, use of this diffraction limit assumes that the effects of turbulence in the Earth's atmosphere can be removed; but with adaptive optics, which will be present on all these big new telescopes, infrared observations will come close to the diffraction limit).

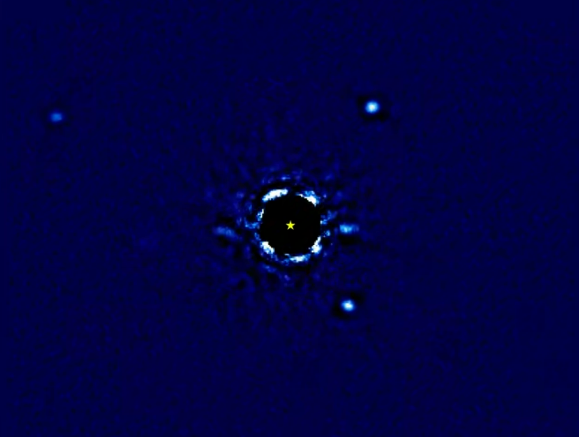

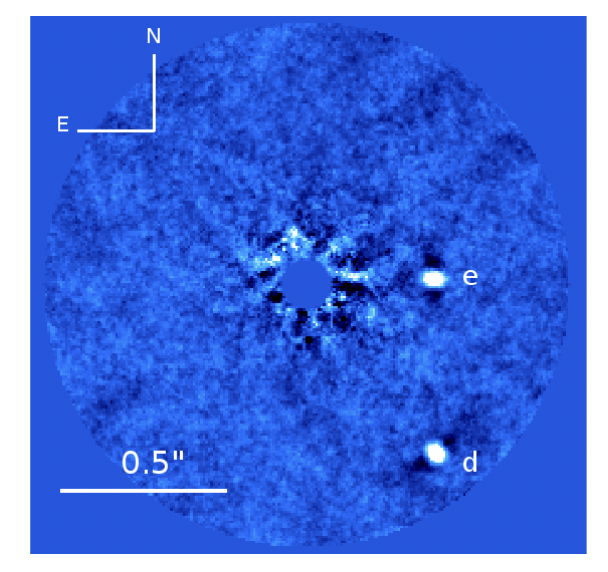

For example, consider exoplanet studies. For example, astronomers who wish to acquire direct imaging of planets around other stars face the problem of separating the light of a very faint point source from the glare of a much brighter, very close star. The picture (and movie) below show planets circling the star HR 8799.

Image and movie of HR 8799 courtesy of

ESO and J. Wang and Christian Marois

This system is relatively close to the Sun, lying only 41 pc away. Despite its proximity, we can't look into the inner regions of the system to check for planets. The innermost of the objects one can see in these images, HR 8799e, has an orbital radius of about 16 AU.

A more recent image of the system was taken with the one of the VLT's 8.3-m telescopes and an adaptive optics system, as described in

The wavelength of this image is λ = 1.63 microns.

Figure 2 taken from

by Zurlo, B., et al., A&A 587, 57 (2016)

The new generation of big telescopes will allow us to explore the regions closer to host stars; in this case, the ELT might detect objects with orbits as small as that of the Earth, or even Venus.

Let's continue to look at the science of exoplanets. Another problem with studying exoplanets is that they are just plain faint: even if we can clearly separate their light from that of their host stars, there just aren't that many photons arriving every second.

To some extent, we can get around this limitation by using the plentiful light of the host star to carry the signal. The technique of http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/exo2024/lectures/transit_spec/transit_spec.html transmission spectroscopy measures small changes in the spectrum of the host star as it passes through a planet's atmosphere during a transit. Smart!

Unfortunately, even this method often runs into problems due to a lack of photons. Spectrographs are not very efficient, as a general rule, due to the complex optics within, which can absorb or scatter a large fraction of the incoming photons. Even the photons that reach the detector have been split into many small groups (based on their wavelengths), and so the number in each spectral bin can be pitifully small. Even JWST, with a diameter of 6.5 m, requires minutes of exposure time to record enough light from a star as bright as mK = 7.2, or HOURS of time for more ordinary exoplanet hosts.

But JWST has a collecting area of only 33 square meters. The next generation of telescopes will have ten times, or twenty times, that area, and so will be able to study exoplanets circling fainter stars. Let's see just how much of a difference this can make. We will compare JWST and ELT.

Q: What is the ratio of collecting areas?

Now, if JWST measures the spectrum of a star, and achieves a particular signal-to-noise ratio, then the ELT could reach the same signal-to-noise ratio for an identical star at a greater distance.

Q: How much farther away could the star be placed and still yield the same S/N when observed by ELT?

The fact that the same results could be achieved for an identical star at a greater distance means that ELT could study stars in a LARGER VOLUME that JWST. If the local density of stars is roughly uniform, then sampling a larger volume means that ELT could study a larger number of stars.

Q: Assuming a uniform distribution of stars, how many more stars could ELT observe than JWST?

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.