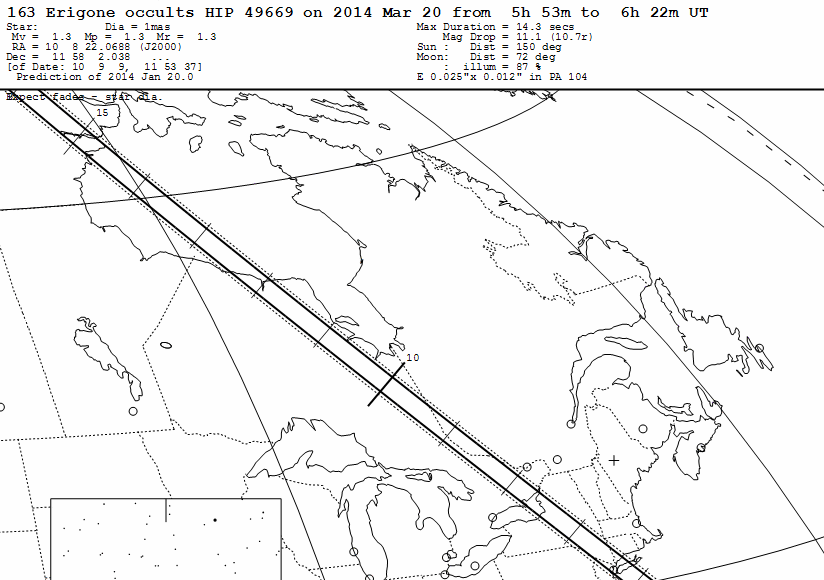

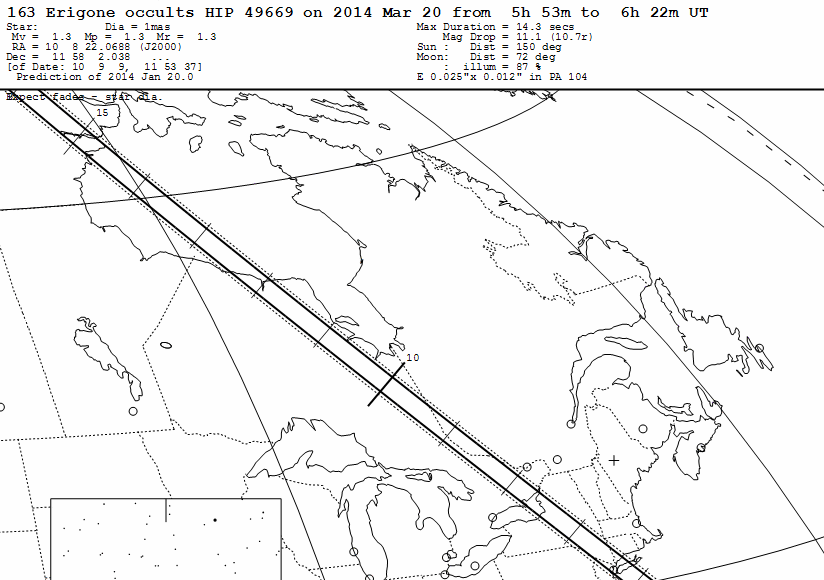

Here in Rochester, on what local date, and at what local time, should we look for the event?

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Our clocks and watches are set to civil time, which is designed to follow the Sun. We call the average time between noon and noon one day, and divide that period into 24 equal hours. It takes roughly 365.25 days for the Earth to revolve around the Sun; in order to keep the calendar in phase with the seasons, we add a leap day every fourth year.

Civil time isn't very useful for astronomical work, but it is the version embedded most deeply into our brains because we use it every day. Therefore, I find it a good idea to include civil times in observing plans, because my brain doesn't function very well late at night. An event which is listed as occuring at 5 AM can be checked simply against my own watch or bedside table.

Most states in the US turn their clocks forward an hour in April, and backward an hour in October, for Daylight Saving Time. The sudden switch makes civil time a very poor choice for any calculations.

For practical purposes, one can think of UT as being the time on clocks in Greenwich, England. In real life, the strict definition is a lot more complicated, but that's irrelevant for us.

Astronomical events are calculated and reported in UT because UT has the same value everywhere. If a variable star is due to enter its eclipse at 5:35 UT, then observers all over the world know when to look. UT is, in essence, a giant clock which can be shared by the whole world.

Observers at different places on Earth must make different corrections to turn their local civil time into UT. Here at RIT,

UT = local time + 5 hours (during Eastern Standard Time)

= local time + 4 hours (during Daylight Saving Time)

That change of one hour due to Daylight Saving Time can be

really annoying.

Here in Rochester, on what local date, and at what local time, should we look for the event?

Suppose that we are studying a variable star which slowly grows fainter and brighter. We record the following:

Tuesday, Jan 16, 2001: faint Wednesday, Mar 21, 2001: very faint Tuesday, Jun 26, 2001: faint Thursday , Aug 2, 2001: medium Wednesday, Oct 31, 2001: bright Thursday , Dec 13, 2001: very bright Sunday, Jan 6, 2002: bright Thursday, Feb 28, 2002: medium Monday, Apr 29, 2002: faint Friday, Jun 7, 2002: very faint

The answer is ... a real pain in the neck to calculate. Our civil calendar has months with different numbers of days, and every fourth year a leap day is added to the end of February. When performing calculations which stretch over more than a single day or two, one must keep track of all these factors.

The Julian Date system (or JD for short) is designed to simplify calculations over long periods of time. Instead of describing a date in terms of

month, day, year

we instead describe it with a single value

number of days since noon, Universal Time on January 1, 4713 BCE

Why that particular choice of a starting date? The most important reason is that it was long, long ago, so that almost any event in recorded history will have a positive value for its Julian Day. That makes calculations extra easy. I you wish, you may read a detailed explanation of this particular choice. The word "Julian", by the way, is derived from the name of the father of the scientist who suggested this system (Julius Scaliger, the father of Joseph Justus Scaliger), not from Julius Caesar.

Thus, instead of "Wednesday, Mar 21, 2001", we could write "Julian Day 2,451,990". Those long strings of numbers can be inconvenient, or hard to remember at times, but look how much simpler they make the determination of period:

2451926 faint 2451990 very faint 2452087 faint 2452124 medium 2452214 bright 2452257 very bright 2452281 bright 2452334 medium 2452394 faint 2452433 very faint

The time from "very faint" to "very faint" again is simply

2452433 - 2451990 = 443 days

Actually, when describing events precisely, one may add the fraction of a day since noon (Greenwich Time) to the Julian Date. For example,

noon UT on March 12, 2002 = JD 2452346

One hour later, 13:00 UT, is 1/24 = 0.04167 of a day later. So we could write

13:00 UT on March 12, 2002 = JD 2452346.04167

When working with Julian Dates over relatively short periods of time -- a few days, weeks or months -- it is often convenient to abbreviate the full Julian Date by omitting the first few digits; after all, those digits are the same in all of the measurements. That is, one could re-write our table of stellar measurements as:

full JD abbrev. JD =

JD - 2450000

2451926 1926 faint

2451990 1990 very faint

2452087 2087 faint

2452124 2124 medium

2452214 2214 bright

2452257 2257 very bright

2452281 2281 bright

2452334 2334 medium

2452394 2394 faint

2452433 2433 very faint

Beware, though: some people shorten the full Julian Date by subtracting an extra half-day (the so-called "Modified Julian Date"). It is very easy to make a mistake of one-half a day when dealing with modified values. It's usually best to quote the entire Julian Date, long as it may be.

Civil time, UT, and JD are all tied to the motion of the Sun. For ordinary human purposes, that makes sense. But astronomers could use a time system which is tied to the stars. The answer: Local Sidereal Time or LST for short.

One way to describe LST is "the current LST is equal to the Right Ascension of a star which is currently at its highest point in the sky." It may help to look at a picture. Let's follow the motion of a star which has a Right Ascension value of 08:00 -- that's eight hours, zero minutes. A few hours after it rises, it is still on the eastern side of the sky:

Two hours later, it reaches its highest altitude in the sky, when it crosses the meridian (a line running from due North to due South through the zenith).

And two hours after that, it is well on its way down towards the western horizon.

We can use the Right Ascension values of stars to define a time system: when a star of RA = 08:00 is crossing the meridian, we say "the Local Sidereal Time is 08:00, or eight hours." Two hours later, a star of RA = 10:00 will be crossing the meridian, and so we'll say "the LST now is ten hours."

The whole point of LST is that it indicates where celestial objects will be in the sky. For example, if the LST = ten hours, then we know

The difference between the current LST and the RA of a star is called the hour angle (or HA for short).

Hour Angle = LST - RA

This is usually measured in hours, and describes how long it has been since the star crossed the meridian. In the series of figures above, the star has

Hour Angle is sometimes used as a substitute for Right Ascension; together with Declination, it uniquely describes the position of a star in the sky. One can also use HA and Declination together to calculate the airmass (which we will discuss in a lecture or two ).

Note that LST is a Local system; an observer in Rochester and an observer in Los Angeles will agree on the UT, but not on the LST.

(LST_in_Rochester - LST_in_Los_Angeles)

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.