Image courtesy of David Nelson

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Just what is an X-ray? There are no exact definitions, but most of the astronomical telescopes which call themselves "X-ray instruments" are sensitive to light within this range:

Energy (keV) 0.1 - 500

Wavelength (Angstrom) 100 - 0.02

Photons of this sort can still penetrate through layers of material, as gamma rays do, but not to the same extent. They have much less energy, so we can in some cases use techniques similar to those developed for optical photons.

Image courtesy of

David Nelson

But since the physical processes which create X-rays and optical photons involve material in very different conditions, we can find and study astronomical objects which would be otherwise completely invisible.

So, what are the methods we can use to build X-ray detectors? Most of the recent devices fall into three categories.

Click on the image below to see an animation, or click here to watch one frame at a time.

Note that the number of initial ionizations depends to some degree on the energy of the incoming X ray. So this sort of device, like a scintillation counter, will measure the energy of the X-ray photon, not just its presence. For example, the ROSAT PSPC had an energy resolution of about 17% at an energy of 6 keV.

Q: What would such an energy resolution in the optical

mean -- say, 17% at a wavelength of 5000 Angstroms?

This is similar to the energy resolution of typical broadband optical filters.

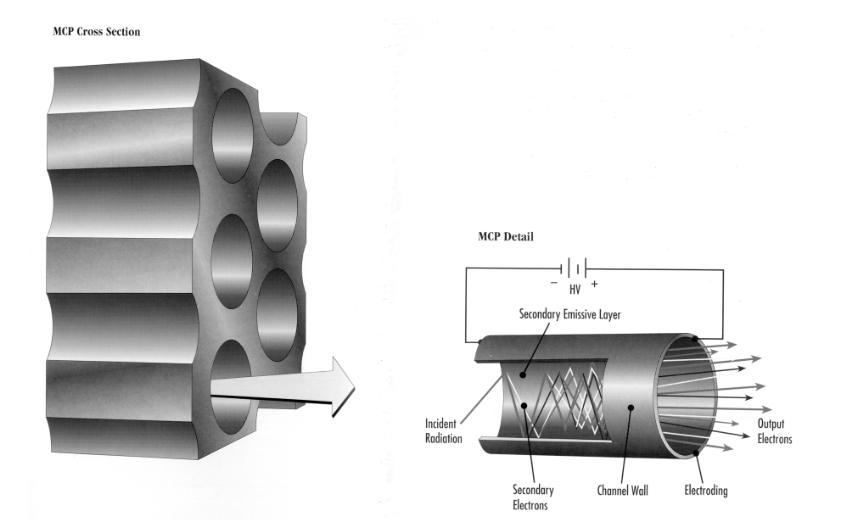

Figure 22.5 taken from

Microchannel plates for photon detection and imaging

in space

by J. Gethyn Timothy

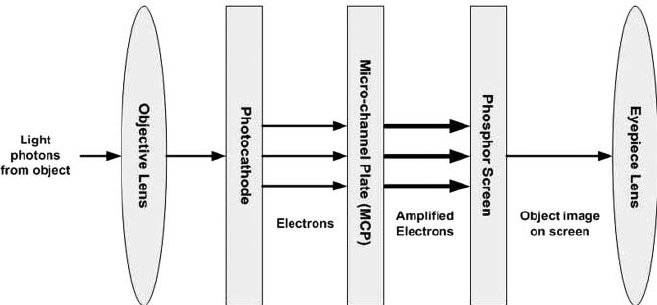

This is very similar to the technology used in night-vision goggles.

Image taken from

Parush et al., Reviews of Human Factors and Ergonomics,

7, 238 (2011)

Image courtesy of

Night Vision Guys and Youtube

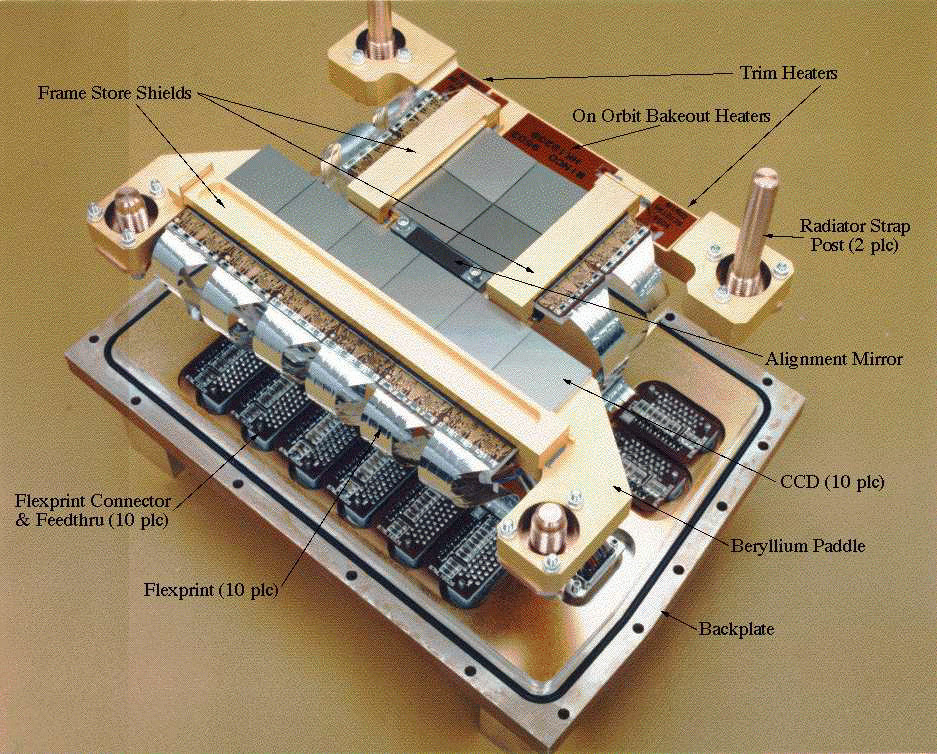

Below is an image of the focal plane of the ACIS instrument on Chandra. You can see 10 CCD chips: the four arranged in a square are used to take images, while the six arranged in a line are used for spectra.

Image courtesy of

CfA and NASA

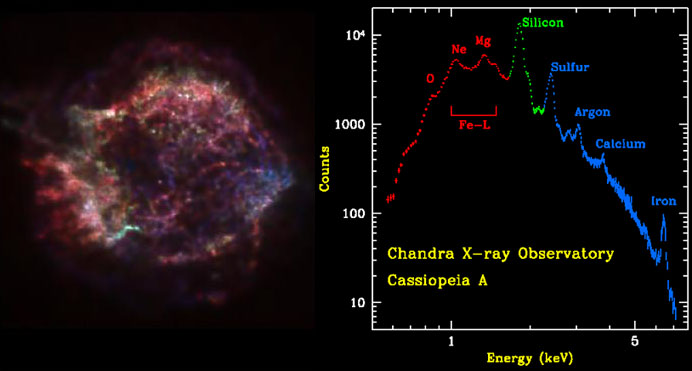

CCDs can be operated in several modes, but one of the common choices for X-ray missions is photon-counting mode. Because X-ray photons arrive so infrequently, one can identify individual events by reading out the chip once a second or so. In essence, one builds up a list of each photon from a source, tagging it with (time, x, y, energy).

If all you need is relatively low spectral resolution, then CCDs can do it all in the X-ray regime!

Image courtesy of

Chandra X-ray Observatory

Those of you familiar with using CCDs in the optical will notice two big differences in this X-ray mode of operation:

A few of the significant X-ray satellites

Let's look in detail at a couple of the recent-ish X-ray satellites which have gathered large amounts of information, to see how they work. I'll choose one from the 1990s (ROSAT) and one from the 2000s (Chandra).

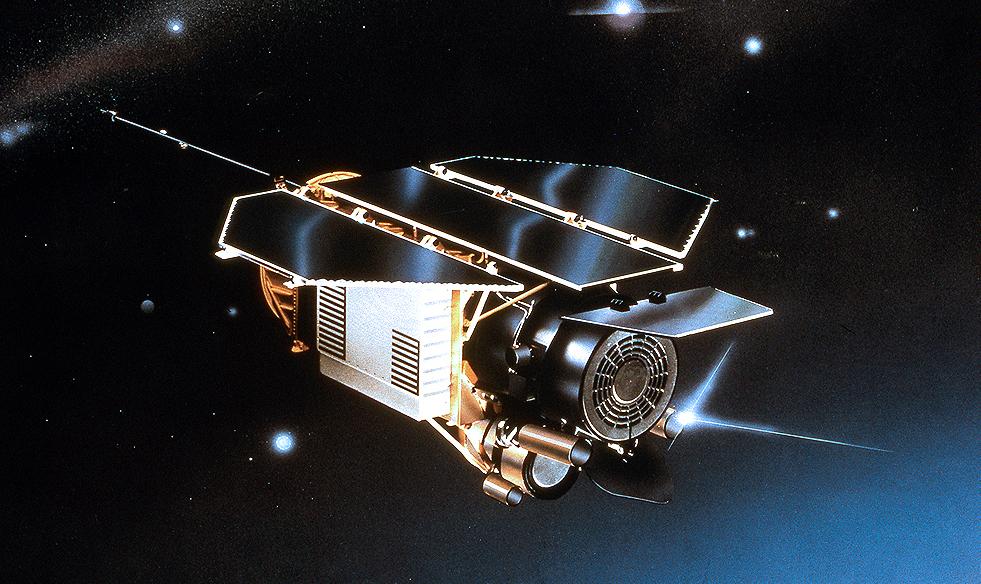

Image courtesy of

the DLR

ROentgen SATellite (ROSAT) was developed under the leadership of the German Aerospace Center, with contributions from the US and the UK. It carried out an important all-sky survey as well as a large number of pointed observations at specific targets. ROSAT was launched in 1990 and made its last observations in 1999.

The instrument was relatively small: the telescope was 85 cm in diameter. The satellite itself was about 3 meters long, but contained several instruments. We'll focus here on just one, the Position Sensitive Proportional Counter (PSPC).

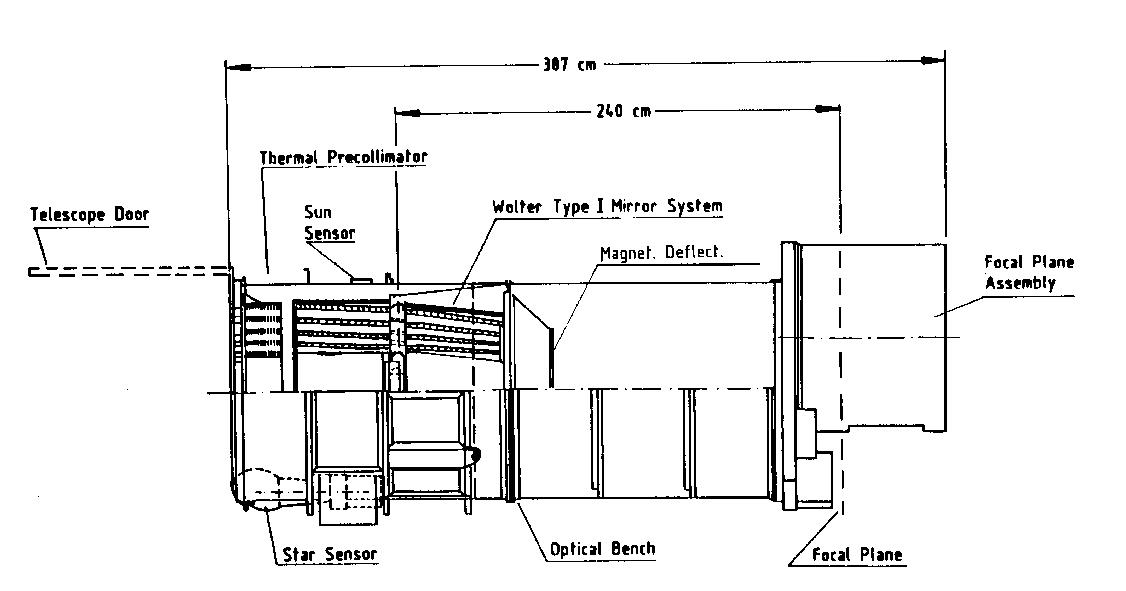

Image taken from the

ROSAT User's Handbook

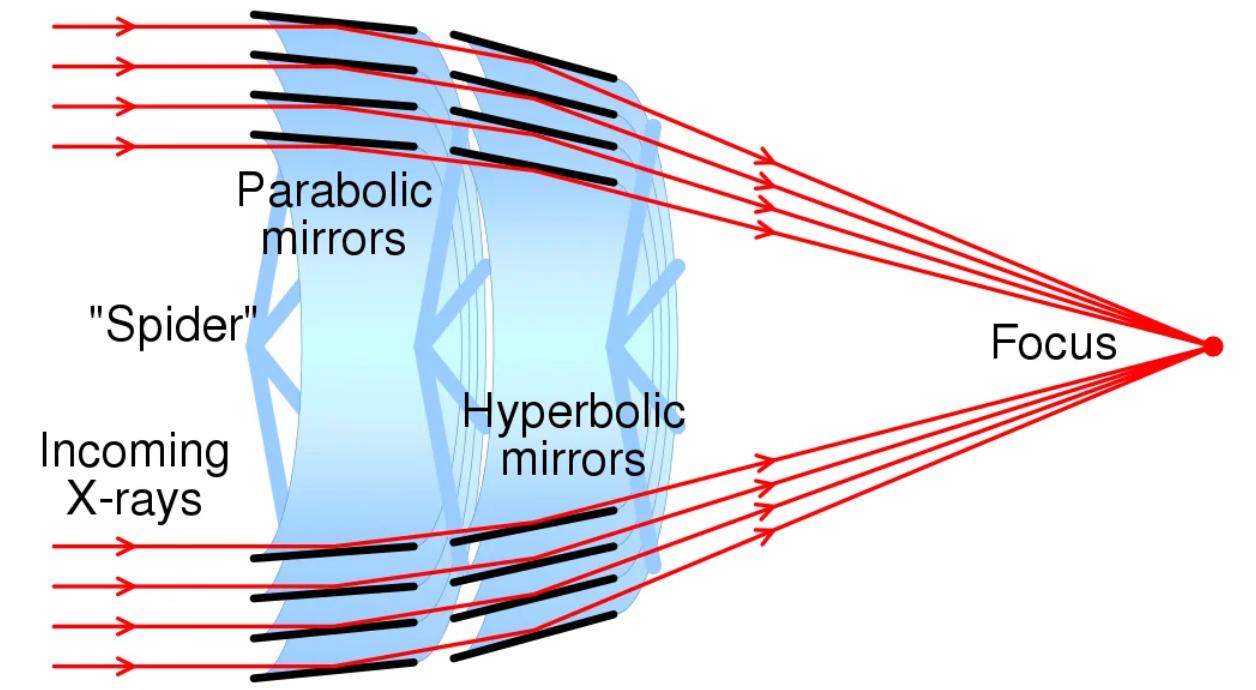

In the diagram above, light enters the telescope from the left, strikes the mirrors near the entrance, and is focused on detectors mounted on the focal plane, at right.

Light strikes mirrors immediately after entering the

telescope aperture.

How does this differ from ordinary telescope design?

For example, how does it differ from the Hubble Space Telescope?

Why is the X-ray telescope designed in this strange manner?

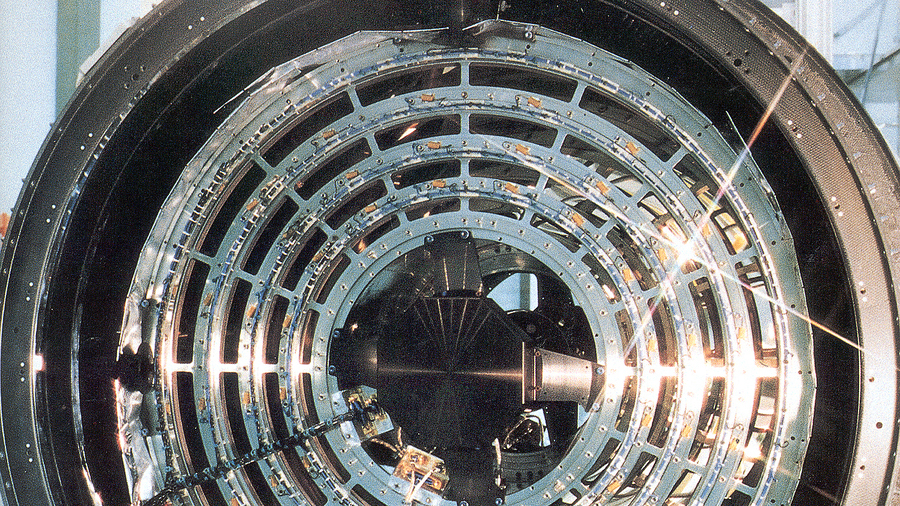

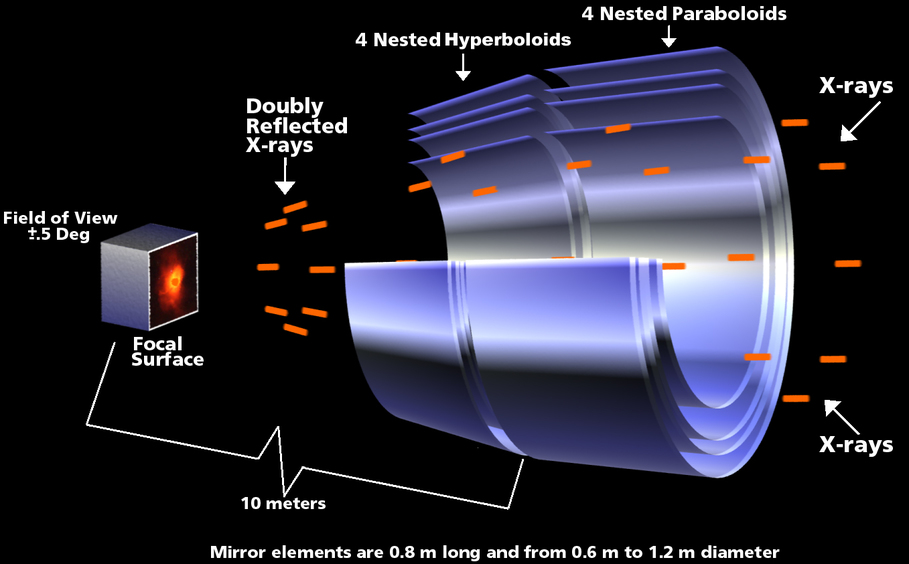

The key difference is the shape of the mirrors. In optical designs, light strikes a mirror at nearly normal incidence (90 degrees from the surface) and bounces nearly straight back. But X rays would mostly go THROUGH a mirror if they hit it at such a direct angle. In order to reflect X rays, one must build grazing incidence mirrors which are tilted nearly edge-on to the target. The picture below shows a star's-eye view of ROSAT; the metal circles are supports for the mirrors, which extend backwards into the telescope.

Image courtesy of

the DLR

Image

courtesy of

Max-Planck-Institut fur extraterrestrische Physik (MPE)

There were four nested "shells" of mirror in two sections: a paraboloid in front, followed by a hyperboloid in back. X rays striking the mirrors at angles of just 1 to 2 degrees would be focused onto the detectors at the far end of the telescope.

Here's a schematic showing the general idea clearly.

Image source unknown, found on

this reddit thread

The XRISM X-ray telescope, launched in 2023, has MANY more mirrors than ROSAT: a total of 203 mirrors in every quadrant, compared to the 4 of ROSAT. Using many mirrors increases the collecting area of the telescope. One can find pictures of these grazing-incidence mirrors for XRISM at

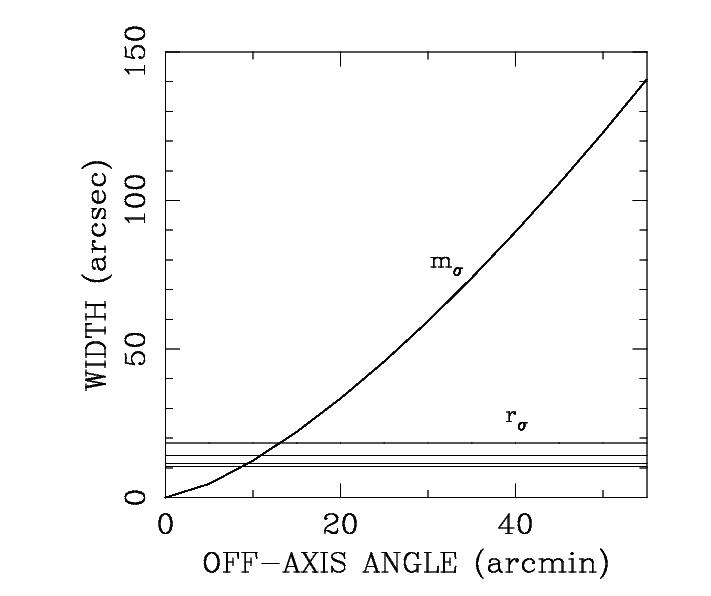

How well did this work? Well, the light was focused into a rather broad Point-Spread Function (PSF); and the size of this PSF grew the farther the source was from the optical axis.

Figure 2.6 taken from

ROSAT User's Handbook

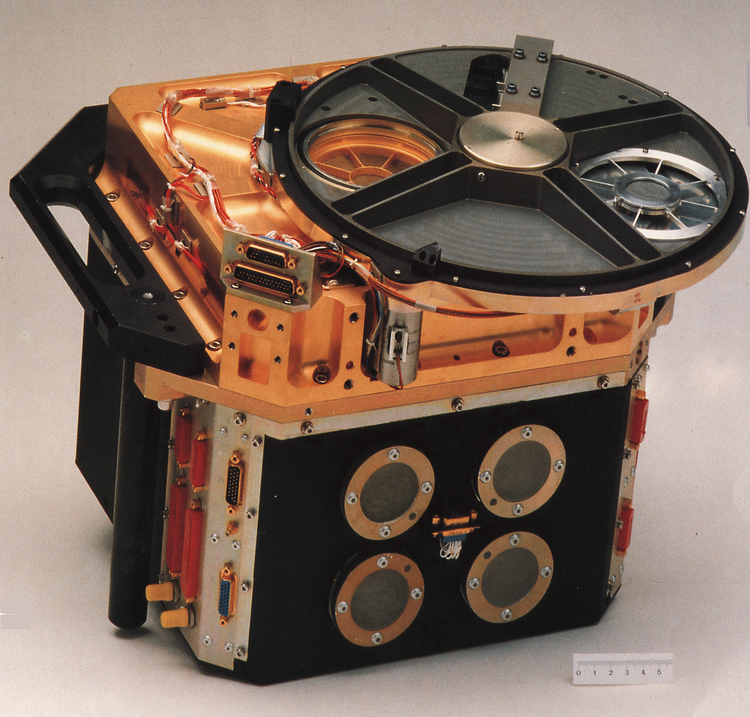

One of the instruments on the focal plane was the Position Sensitive Proportional Counter (PSPC)

Image courtesy of

the DLR

The PSPC consisted of proportional counters behind an octagonal structure. Electrical wires laid out in two perpendicular layers collected the electrons knocked free by X-rays entering the instruments. Each layer of wires provided the location of the X-ray in one direction, so the two working together allowed scientists to pin down the position of each X-ray in the focal plane. The device could measure the energy of each photon to about 30%.

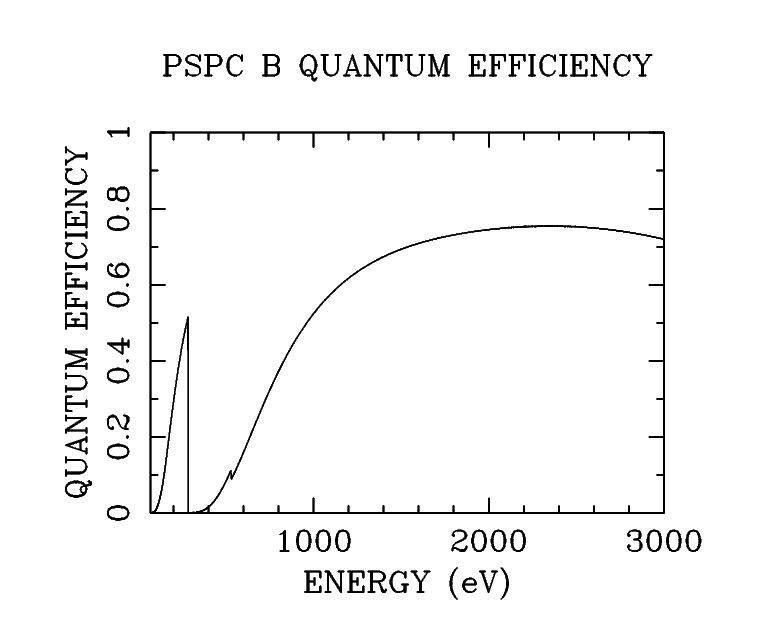

The PSPC was most sensitive to X-rays with energies of a few keV.

Figure 3.5 taken from

ROSAT User's Handbook

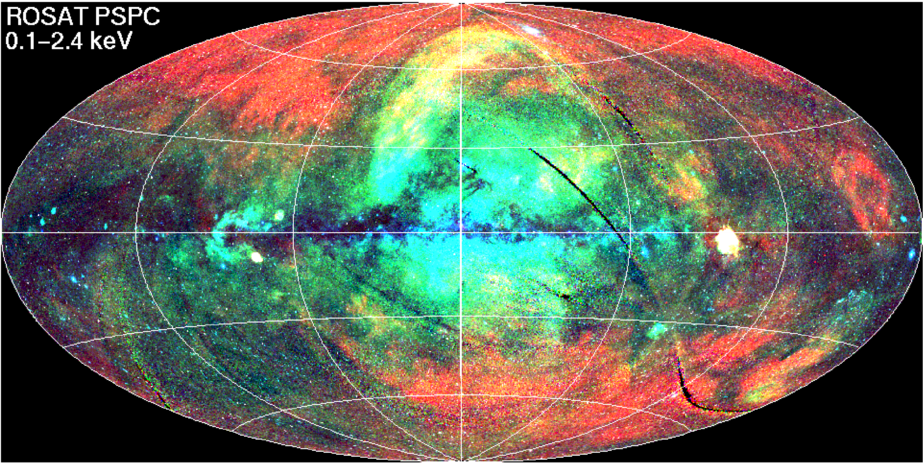

The PSPC was used to create a really good map

of the entire sky in X-rays,

the

ROSAT All-Sky Survey.

Image courtesy of

the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics .

Hmmm Vela X-1?

Q: What does the Andromeda Galaxy look like in the PSPC?

Use the SkyView Query Form

and choose the "PSPC 2.0-deg int" option.

Specify an image size of 600 pixels, and try two fields of view:

3.0 degrees wide

0.5 degrees wide

What do you see?

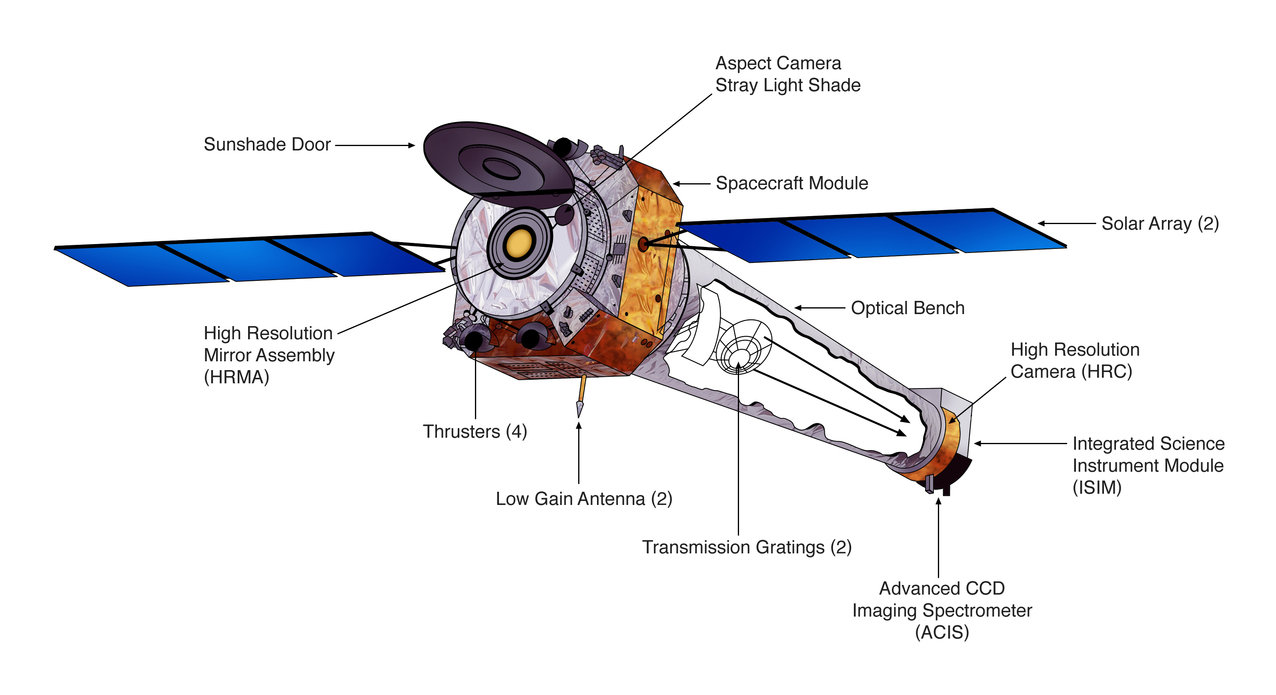

Let's now switch to a more recent X-ray satellite: Chandra, aka AXAF, one of NASA's four Great Observatories, launched in July, 1999, and still active.

Image courtesy of

NGST & NASA/CXC

This is a BIG satellite. The main body of the system stretches about 10 meters from the nested grazing-incidence mirrors to the focal plane.

Q: How was this large satellite carried into orbit?

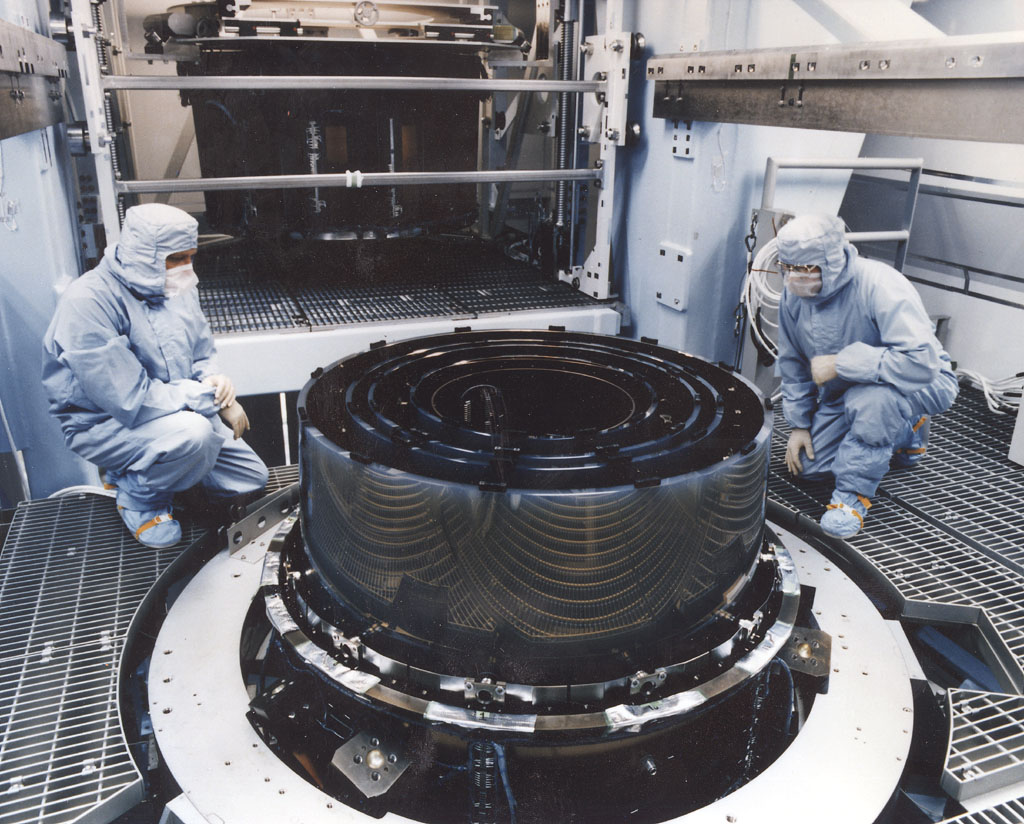

The mirrors on Chandra are similar to those on ROSAT: four pairs of nested mirrors, with paraboloids in front and hyperboloids behind them. The aperture is larger, though: up to 1.2 meters in diameter, versus 0.83 meters for ROSAT. The focal length is also larger, which allows Chandra to sample the sky on a finer scale. These mirrors were made right here in Rochester by Eastman Kodak!

Image courtesy of

Eastman Kodak

Image courtesy of

NASA/CXC/D.Berry

Q: The focal length of Chandra is about 10 meters.

Some of its detectors have pixels about 10 microns in size.

What is the angular scale of each pixel on the focal plane?

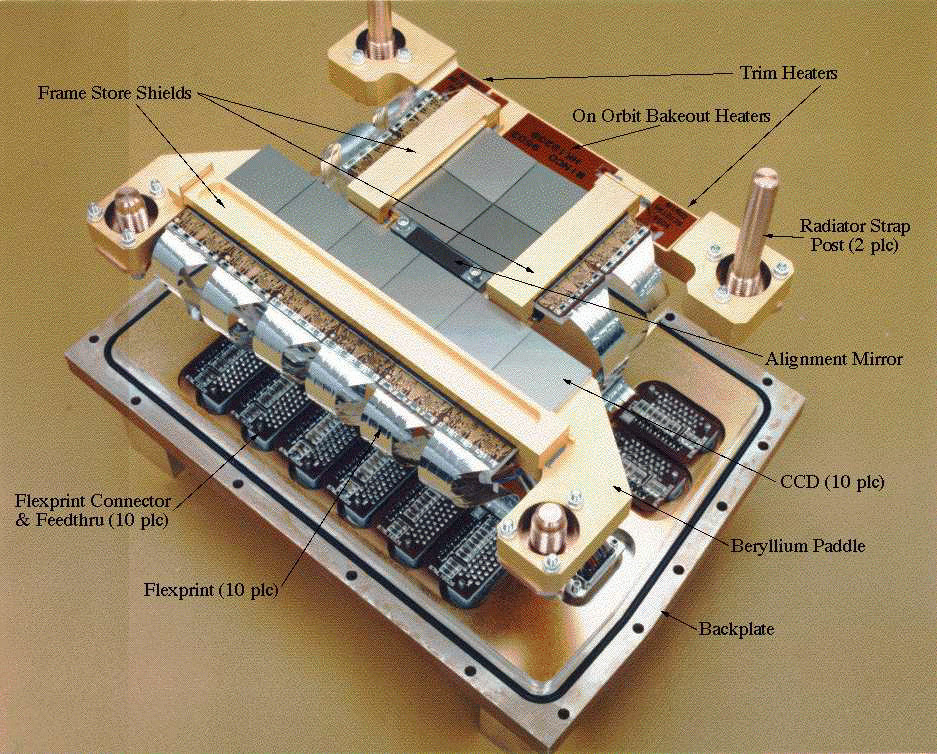

On the focal plane are several instruments. There's the afore-mentioned Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer (ACIS), two arrays of CCDs for both imaging and spectroscopy ...

Image courtesy of

CfA and NASA

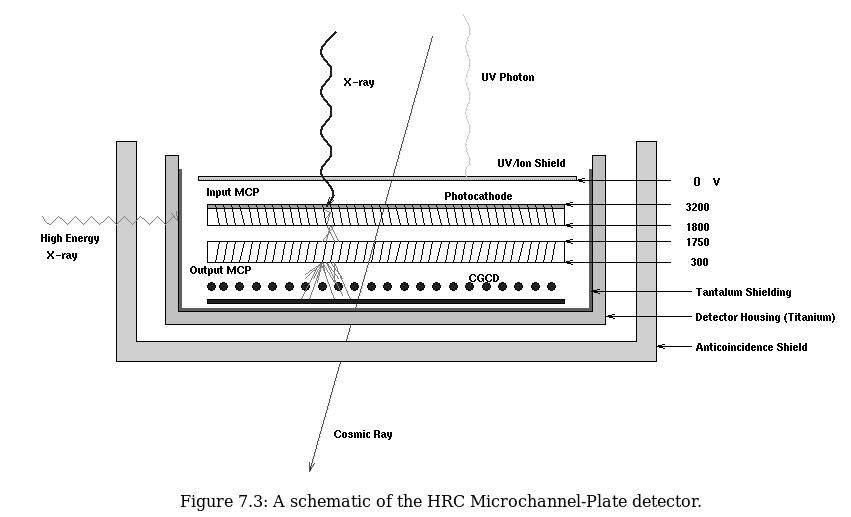

... and there's also the High Resolution Camera (HRC), which is based on a microchannel plate.

Figure 7.3 taken from

Chandra Proposers' Observatory Guide

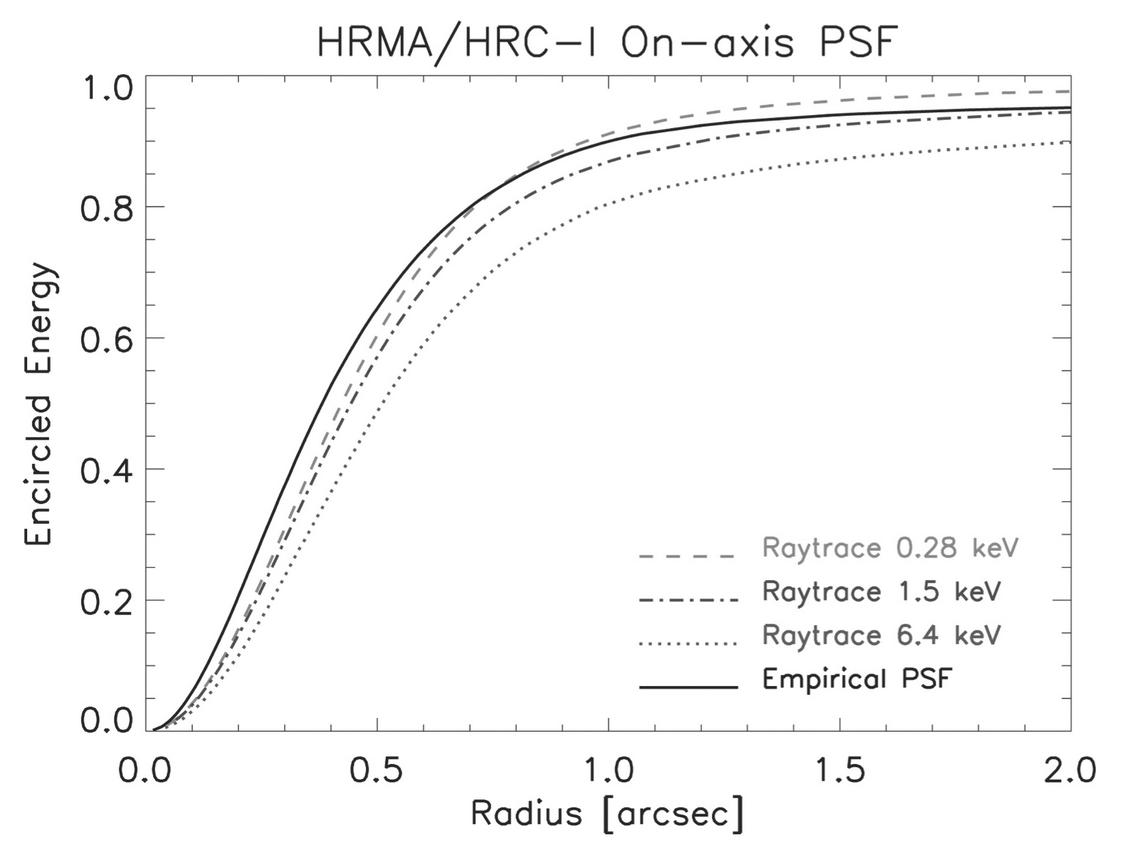

The HRC provides the highest spatial resolution, producing a PSF roughly one arcsecond in size:

Figure 7.5 taken from

The Chandra Proposers' Observatory Guide

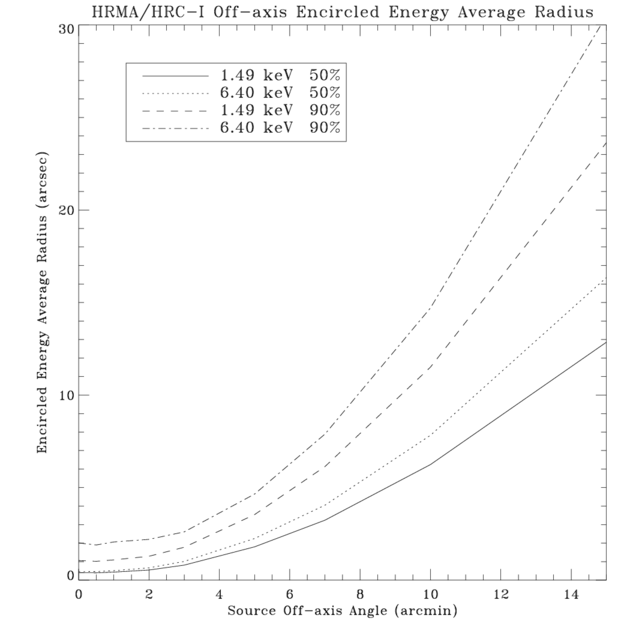

But note that the PSF degrades quite quickly for sources which are off the central optical axis:

Figure 7.7 taken from

The Chandra Proposers' Observatory Guide

The HRC is sensitive to photons with energies between 0.1 and 10 keV. The ACIS has a similar range, though some of its CCD chips (the frontside-illuminated ones) have low quantum efficiencies below 1.0 keV.

Chandra has not carried out a survey of the entire sky; instead, like HST, it moves from one target to the next, often spending very long intervals staring at one region of the sky. Those long intervals are required because each X-ray carries a lot of energy, and so typical sources produce only small numbers of photons each second (or minute).

Q: Look at this week's schedule for Chandra. What is the

typical exposure time for science targets?

Are most of the observations concentrating on

imaging, or spectroscopy? How can you tell?

As an example of Chandra's performance, let's look at M31 again. Compare the image below, which is about 0.5 degrees on a side, with your earlier pictures of M31 taken by ROSAT.

(Here are my versions of the ROSAT images, in case you need them. Or if you are really lazy ... )

Image of M31 taken by Chandra,

courtesy of

NASA/UMass/Z.Li & Q.D.Wang

The (bleak-ish?) future of X-ray astronomy

One of the drawbacks to X-ray astronomy is the cost. There's really little one can do without a satellite in space; yes, sounding rockets have some uses, but they generally don't provide the large amounts of data, nor serve the large numbers of scientists, that a satellite can. The price for the launch alone of a medium-sized satellite is pretty steep: the NuSTAR mission , which has a mass of only a few hundred kg, cost roughly $36 million to launch, with an overall pricetag of around $170 million.

Take a look at a list of the currently active X-ray astronomy satellites, courtesy (mostly) of NASA's "Imagine the Universe!"

| Chandra | July 1999 - present |

| XMM | December 1999 - present |

| Swift | November 2004 - present |

| Suzaku (ASTRO-E2) | July 2005 - Sep 2015 |

| MAXI | July 2009 - present |

| NuSTAR | June 2012 - present |

| ASTROSAT | September 2015 - present |

| NICER | June 2017 - present |

| Spectr-RG | July 2019 - present |

| IXPE | Dec 2021 - present |

| XRISM | Sep 2023 - present |

| SVOM | June 2024 - present |

And when I say "active," I mean "active." Look at the most recent issues of The Astronomer's Telegram, which distributes the very latest discoveries and breaking news.

Q: How many of the eleven most recent telegrams

involve X-ray observations?

Q: How many different X-ray telescopes have contributed

to these recent discoveries?

The next big X-ray mission is

the ESA's Athena telescope,

which is planned for launch in ...

2028 late 2030s.

When I first created this webpage in 2017, the date was 2028, but apparently the schedule has slipped in the past year.This was originally going to be an international collaboration, involving American, European, and Japanese astronomers, but after some troubles, the ESA decided to go for it alone.Update Sep 2019: launch planned for 2031.

Update Sep 2022: mission may be redesigned to cut costs.

Update Sep 2023: launched now planned for 2035

Update Jan 2025: launched now planned for "the second half of the 2030s."

NASA has solicited many concepts for future X-ray missions, but none are currently on the books, as far as I know.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.