Minamoto no Yoshitsune

Historical Periods in Japan

Heian 794 - 1192

Kamakura 1192 - 1336

Muromachi 1336 - 1573

Azura-Muromachi 1568 - 1600

Tokugawa 1600 - 1868

Meiji 1868 - 1912

Yoshitsune lived at the very end of the Heian period;

his brother's ascendancy to Shogun marked the beginning

of the Kamakura period.

It was in the Muromachi period that much of the Yoshitsune

literature was written:

- 'Gunki monogatari' ('war tales')

- are stories based on

real episodes from Japanese history. However,

they are often modified significantly for

dramatic purposes. Although early examples,

such as the 'Heiki Monogatari', portray Yoshitsune

as an active warrior, the later tales emphasize

his tragic nature and cultural sophistication.

'Gikeiki' is a collection of

stories about the youth and fugitive years of

Yoshitsune, written in Muromachi circa 1400

- Noh dramas

-

combine music and singing and dancing to tell

a story.

14 of the 240 Noh dramas in the current

repertoire, such as 'Ataka' and 'Funa Benkei',

tell stories about Yoshitsune

and his followers.

Most Noh plays were written in the Muromachi period.

- 'Kouwaka no mai' dances

-

told stories with a combination

of music and motion, similar perhaps to the

Noh dramas. They flourished in the late

Muromachi and early Tokugawa periods, but

disappeared before the Meiji restoration.

14 of the 44 surviving texts are based on Yoshitsune.

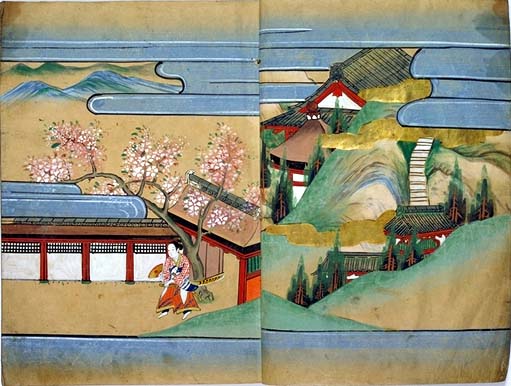

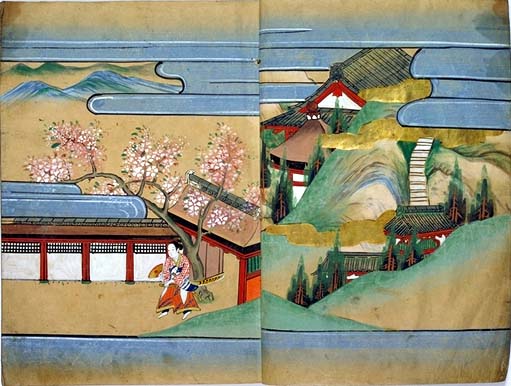

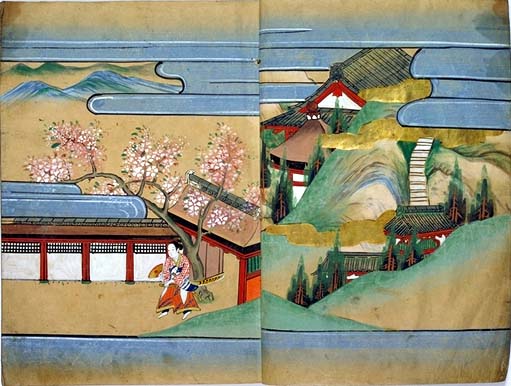

- 'Otogi zoushi' and 'chusei shousetsu'

-

are illustrated

stories, written anonymously and aimed at

a juvenile market. Most were written

in the Muromachi and early Edo periods.

There are 16 'otogi zoushi' about heroes,

and Yoshitsune appears in 8 of them.

Even though in real life, Yoshitsune became famous

through his genius in battle,

in Japanese literature, he appears as a very

different person.

Authors of the Muromachi period looked back to the Heian

times for inspiration. Their ideal men are not rough warriors

striding across the battlefield, but sensitive poets who

mourn the transience of life.

In most of the Japanese literature,

Yoshitsune does things like

- play his flute

- write poetry

- have love affairs

- watch the moon

- muse upon the fleeting nature of man's life

It is his surrounding characters --

Benkei the monk, Shizuka his mistress --

who carry the action.

For example,

- In the Noh play 'Funa Benkei', Yoshitsune and his

party are crossing the sea in a boat when the

angry spirit of Taira no Tomomori appears.

Tomomori was one of the leaders of the Taira

clan whom Yoshitsune's army defeated years earlier.

Tomomori's spirit tries to drag Yoshitsune to the

bottom of the sea. Benkei saves Yoshitsune by

praying to the Buddhist deities.

- In the Noh play 'Ataka', Yoshitsune and his followers,

fleeing the forces of his brother, are stopped at

a checkpoint. Benkei does all talking while Yoshitsune

is disguised as a baggage carrier. The officer of the barrier

grows suspicious of them, so Benkei beats Yoshitsune

to prove that the boy is nothing but a lowly servant.

Apparently,

many Japanese people in the past --

and perhaps today? --

admire tragic figures:

men and women who suffer an unhappy fate,

who are aware of their destiny yet powerless

to change it.

The pathos of these figures has a special

term in Japanese:

mono no aware.

Yoshitsune, due to his noble birth

quick rise to fame, long flight from the hostile

forces and early death,

provides a perfect frame

into which Japanese authors can

place their own invented stories.

References:

- "Yoshitsune: A Fifteenth-century Japanese Chronicle",

Helen Craig McCullough, Stanford University Press, 1966

- "Kouwaka: Ballad Dramas of Japan's Heroic Age",

James T. Araki,

Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol 82, p. 545 (1962)

- Exhibition of otogi zoshi from the Kyoto University Library,

http://edb.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/exhibit-e/otogi/cover/index.html

- Examples of otogi zoshi from the Keio University Zumi project

"http://dbs.humi.keio.ac.jp/naraehon/about/index-e.html"

- 'Funa Benkei' Noh drama description and pictures,

http://www.the-noh.com/en/plays/data/program_003.html

- 'Ataka' Noh drama description and pictures,

http://www.the-noh.com/en/plays/data/program_009.html