If you read the Astronomy Picture of the Day for Aug 27, 2007 , or any newspaper in the past few weeks, you may be wondering, "What do they mean by a big void in the universe?"

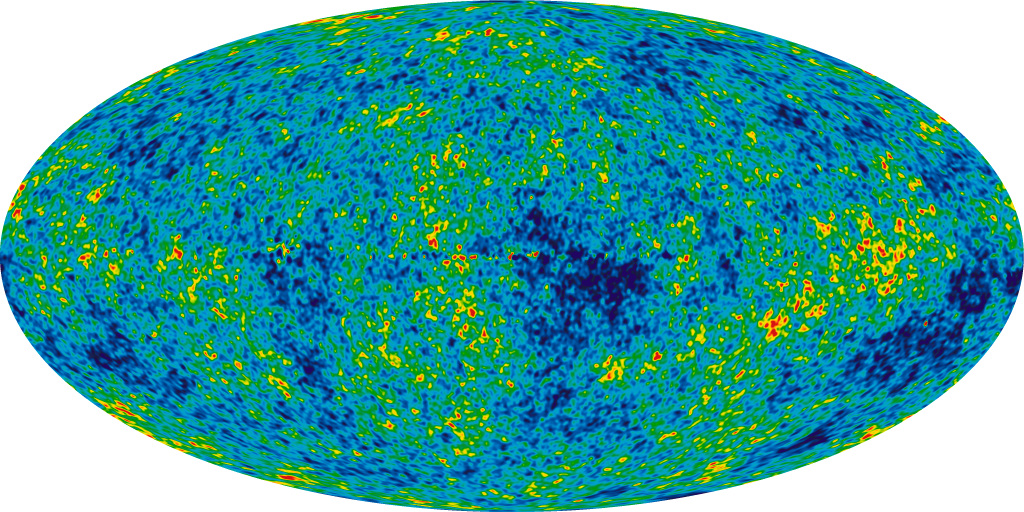

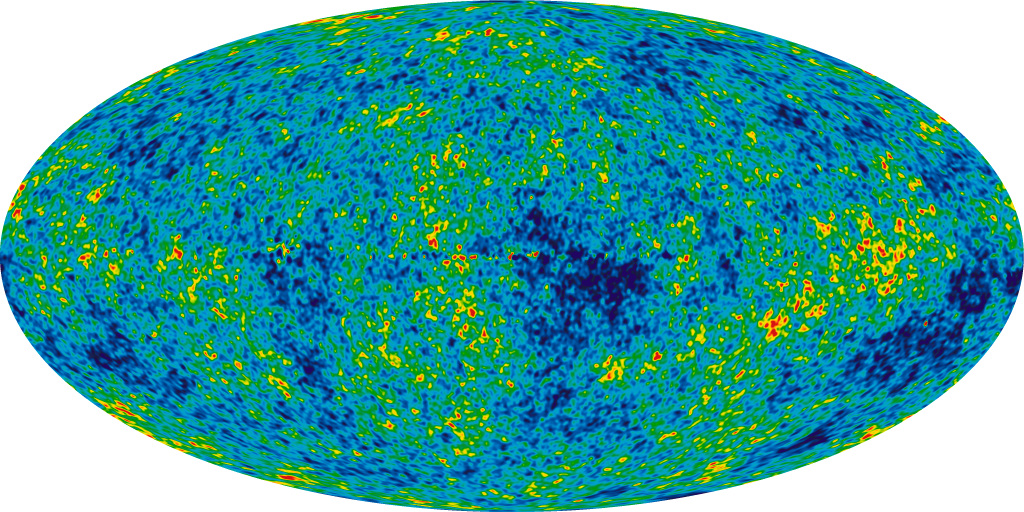

The story starts around 2004, when the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) released a map of the microwave background based on 3 years of measurements.

Scientists studied the tiny fluctuations (shown above with red meaning "slightly warmer" and blue "slightly colder") in the CMB very carefully. For the most part, the fluctuations were consistent with the statistics of ordinary random processes. However, there were a few places in the microwave sky which seemed too warm or too cool to fit into the expected statistical distribution of temperature. One of these, mentioned by Vielva et al., ApJ 609, 22, 2004 , was called "the cold spot."

What could be causing the cold spot? There were (at least) two possibilities:

In 2007, a team of scientists at University of Minnesota tested the second idea. They used a survey by the VLA radio telescope in New Mexico to look for ordinary galaxies in the general direction of the cold spot. They found that at the location of the cold spot, there was much less radio emission from galaxies than usual.

They also counted the number of extragalactic radio sources (galaxies which emit radio waves) in the neighborhood of the cold spot. You can see from their graph below that the number of radio galaxies near the location of the cold spot is much lower than the number of galaxies in other nearby directions.

What does this mean? It suggests that there is a lower-than-average density of galaxies in space along the line of sight to the cold spot.

As microwaves from the CMB fly through most of the universe, they gain a little extra bit of energy via the Integrated Sachs Wolfe effect. The basic idea is that a photon gains some energy as it falls into the gravitational potential well of a galaxy cluster; under ordinary circumstances, it would lose exactly the same amount of energy when it climbed up out of that potential well to leave the galaxy cluster. However, if the universe is expanding, the gravitational potential well of the cluster becomes just a bit shallower as space expands; as a result, the photon doesn't have to climb out of as deep a well as it fell in. It ends up gaining a teeny bit of energy by flying through the cluster.

In a region which has very few galaxies and few galaxy clusters -- like the void pictured above -- microwave photons don't gain this teeny boost in energy as they fly through space. So, compared to all the OTHER microwave photons, the ones which passed through the void appear to have a bit less energy. That makes the CMB in that direction appear a bit colder than usual.

Cosmologists will be spending lots of time studying this particular region of space very carefully, using other sorts of telescopes -- optical, X-ray, infrared -- to see if this region of space really DOES have fewer galaxies than normal. We need to confirm the indications from the radio surveys before we can conclude confidently that there really is a "big void" in this region of the universe.