Movie courtesy of The ESA

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Much of the material herein is taken from the excellent work by Emily Lakdawalla and other writers for the Planetary Society Blog.

Movie courtesy of

The ESA

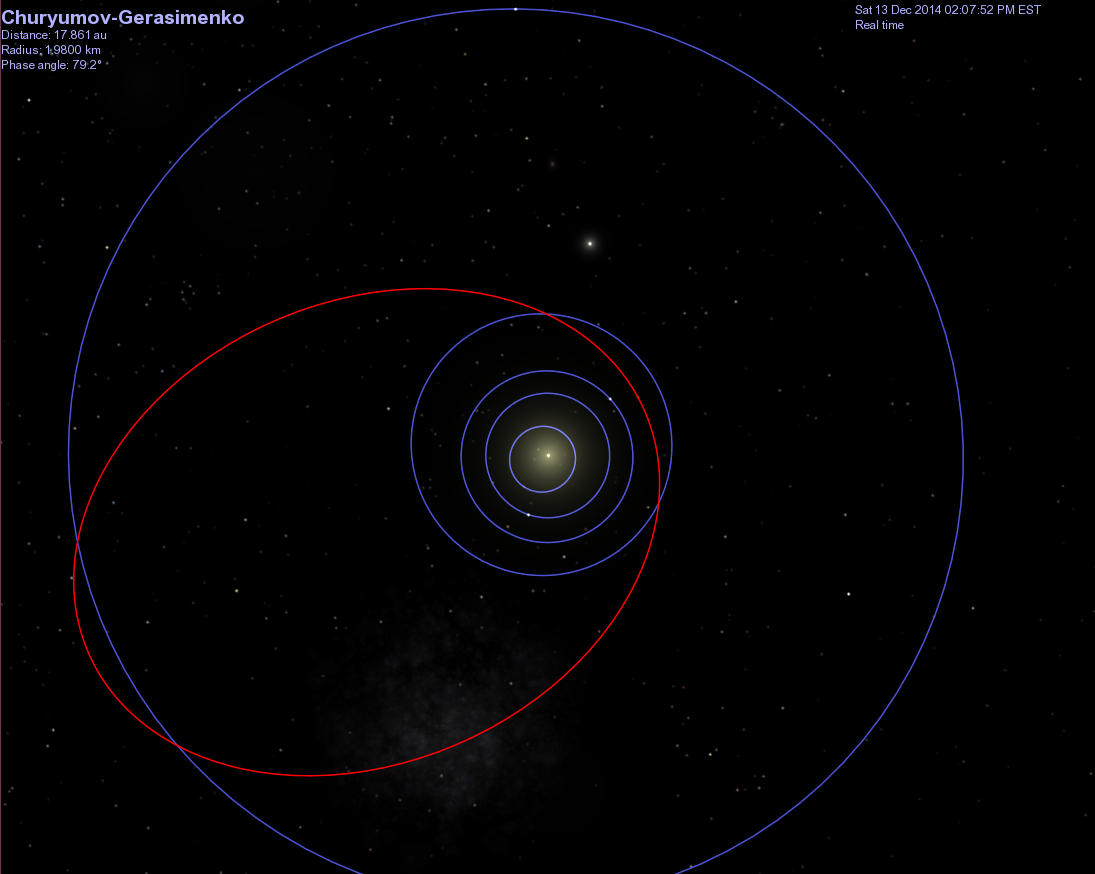

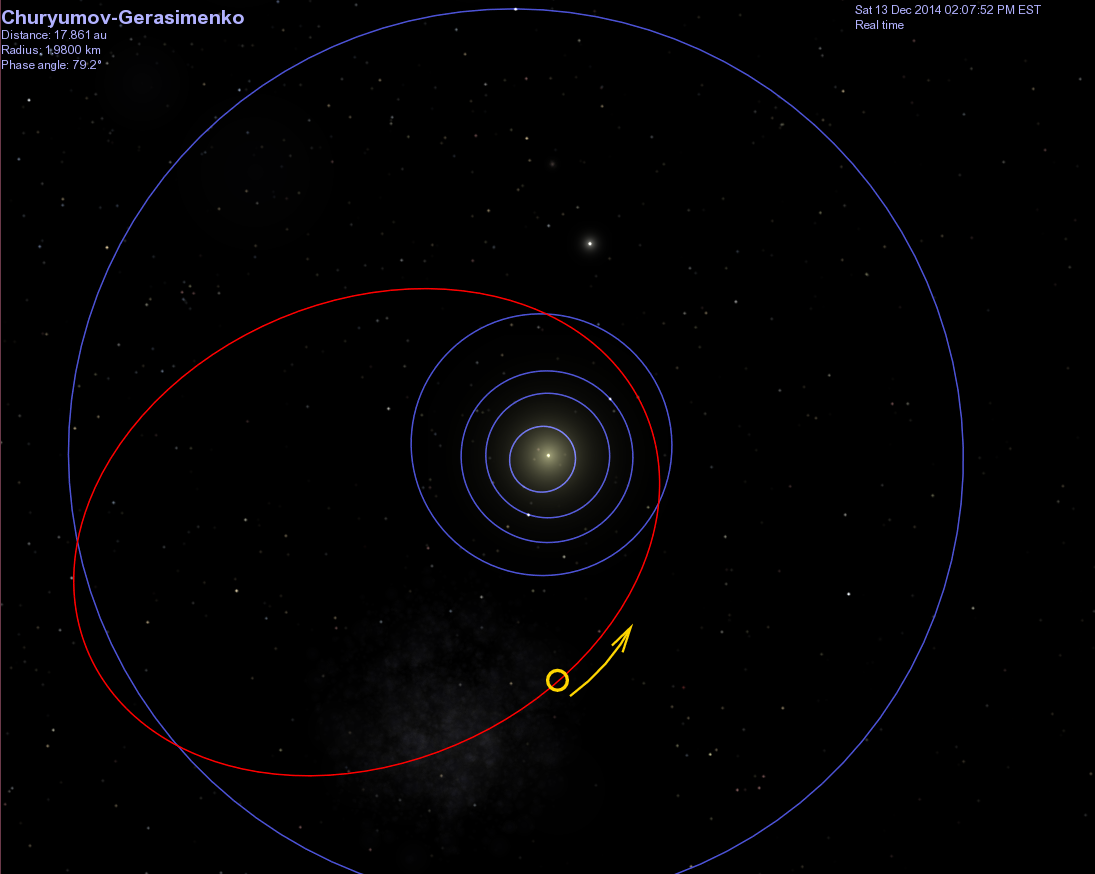

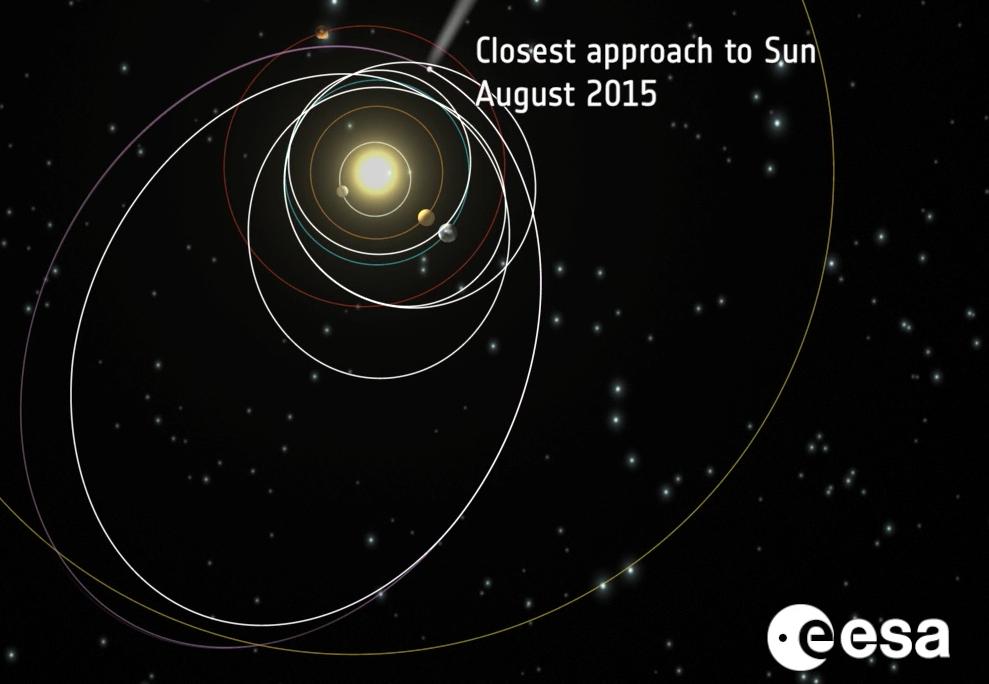

Comet 67P has an orbit that ranges from as far out as Jupiter to a bit closer than Mars. It is always more distant from the Sun than the Earth.

Right now, it is about half-way on the inward portion of its orbit, heading towards the warmth of the inner solar system.

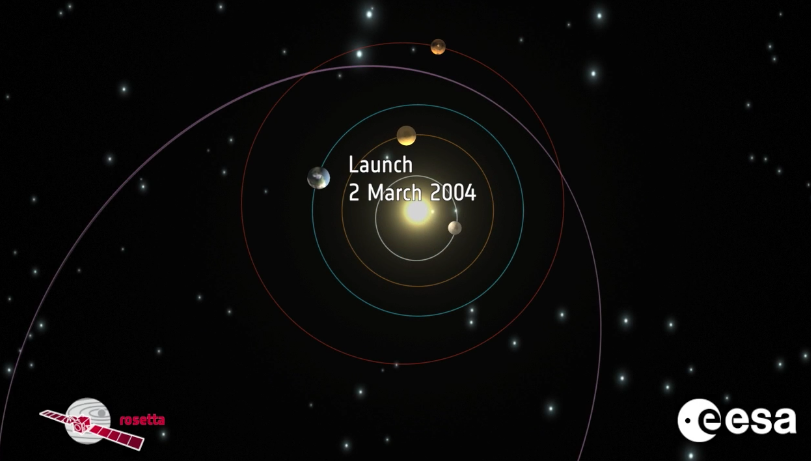

Obviously, Rosetta is there, too. How did it reach this point in space? The answer: in a very roundabout way. Rosetta was launched way back in March, 2004, so it has been travelling for over 10 years.

Why has it taken so long? The European Space Agency team found a way to save lots of fuel by using four planetary flybys to give the spacecraft a series of boosts. This special path meant that the rocket used to lift Rosetta up off the Earth could be relatively small and inexpensive.

Click on the picture below to see a movie of Rosetta's journey.

Movie courtesy of

The ESA

Rosetta is a pretty big spacecraft -- its main body is about the size of a small truck:

.... but it grows much larger when it spreads out its solar panels.

The mass of the spacecraft started out at about 3000 kg, but a lot of that was its propellant. By the time it reached the comet, its mass was only about half its initial value.

Riding aboard Rosetta is the little lander, called "Philae". It's about the size of a deluxe coffee maker:

Image courtesy of the BBC.

It has quite a few instruments of its own.

On Nov 5, 2014, cameras watched as the lander made its approach to the comet. Would it manage to land safely?

The plan was for

The first steps went smoothly:

Image courtesy of

ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

And hours later, the lander touched down ----

---- or so it was thought.

Within a few hours after THAT, however, it became clear that things weren't as expected. After much confusion, it became clear that

the lander had bounced off the surface --- twice

What happened?

So, instead of hitting and sticking, the lander hit the surface and then bounced twice. One big bounce, lasting about two hours, and then a smaller bounce, lasting only about 20 minutes(?). Eventually, the lander settled down onto the surface, but not in a secure manner, and probably not solidly balanced on all three legs.

How could the lander fly so far up above the surface before falling down again? The key is the very, very weak gravity around Comet 67P. The surface gravity there is only about 0.002 percent the strength of Earth's gravity, so a typical adult human would weigh less than one ounce! If you were standing on the surface of the comet, and jump upwards at just about one mile per hour, you would go up -- up -- up -- and never fall back! The escape velocity from the surface is less than 1 meter per second.

Here's a shot of the surface of the initial landing site, taken just a few seconds before the lander touched down and bounced away again. The picture shows a region about 40-by-40 meters wide -- roughly half the size of a soccer field. The big rock at upper right is about 5 meters wide.

Image courtesy of

ESA / Rosetta / Philae / ROLIS / DLR

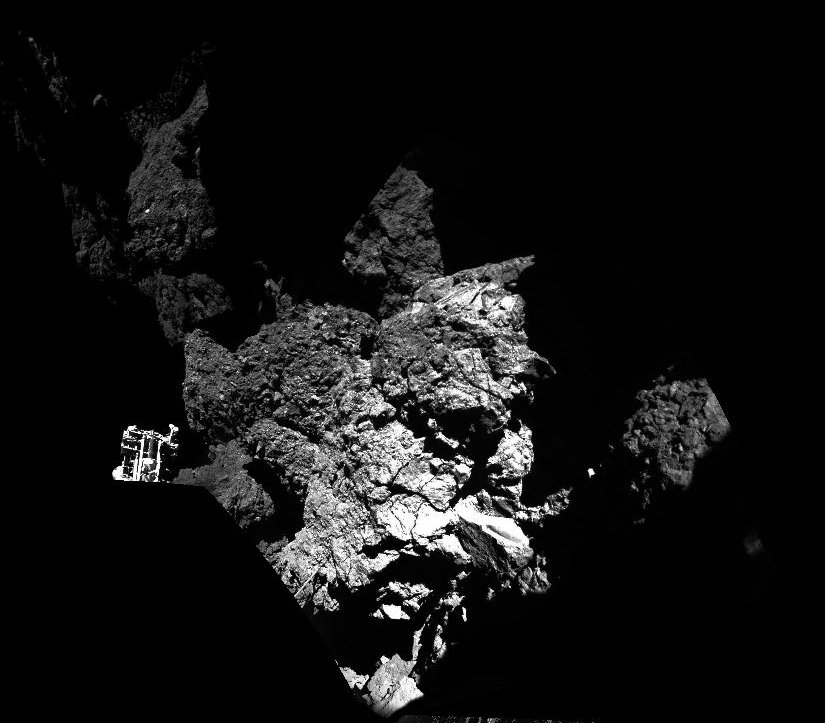

After the bounces, when Philae had finally reached a resting position on the comet's surface, it took this picture with its CIVA camera. The metal structure near the top is one of Philae's feet.

Image courtesy of

ESA/Rosetta/Philae/CIVA

The big problem with this new landing site is that it lies in a shadowy region, so that the spacecraft only gets sunlight for about 1.5 hours of each 12-hour comet day, instead of the roughly 6 hours which was expected. That is, unfortunately, not long enough for Philae's solar panels to recharge its batteries.

What's worse is that the batteries drain during the long night, as the spacecraft tries to keep itself warm.

The result: within just a few days, Philae ran out of power and shut down.

Well, one of the first things we learned, long before Philae took off for the surface, was the mass and density of comet 67P. Rosetta was able to take pictures which can be used to determine the size and volume of the comet, and the subtle changes to its motions caused by the gravity of 67P can be used to estimate the mass of the comet. We now know that the comet has

This tells us that the comet is less like a ball of ice (which has density 1000 kg per cubic meter) than a ball of fluffy snow.

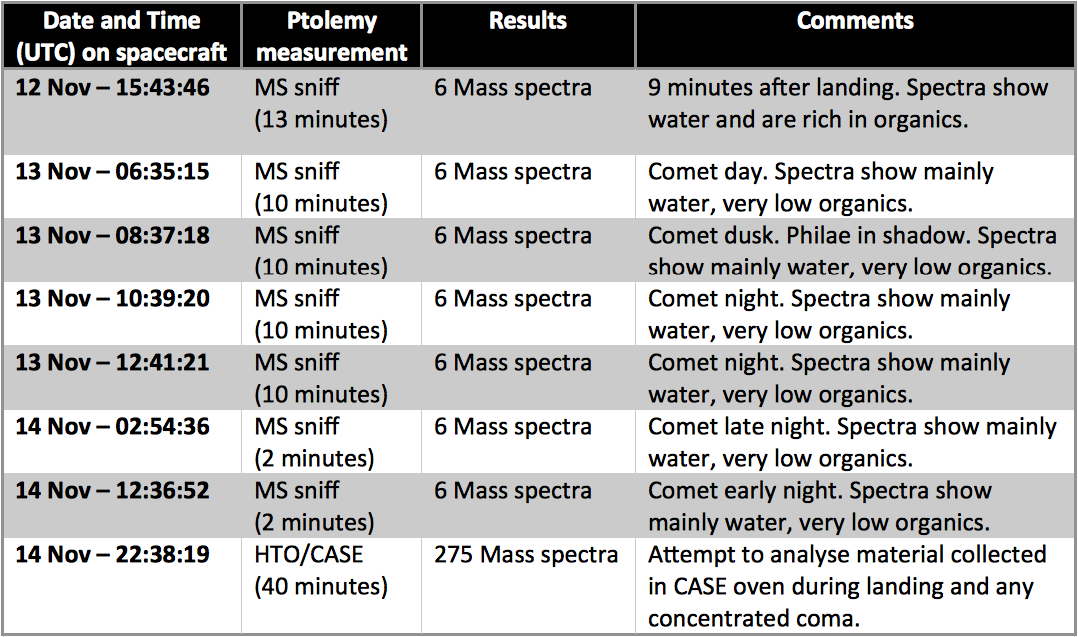

Now, as for the science results from the Philae lander, this talk is just about one week too early.

But some tidbits of information have come out.

The COSAC instrument on the lander was able to sample the very, very thin atmosphere near the comet's surface. The team released a statement which included this sentence:

Cosac was able to ''sniff'' the atmosphere and detect the first organic molecules after landing. Analysis of the spectra and the identification of the molecules are continuing.

Of course, the word "organic" simply means "containing carbon atoms", so this doesn't tell us much.

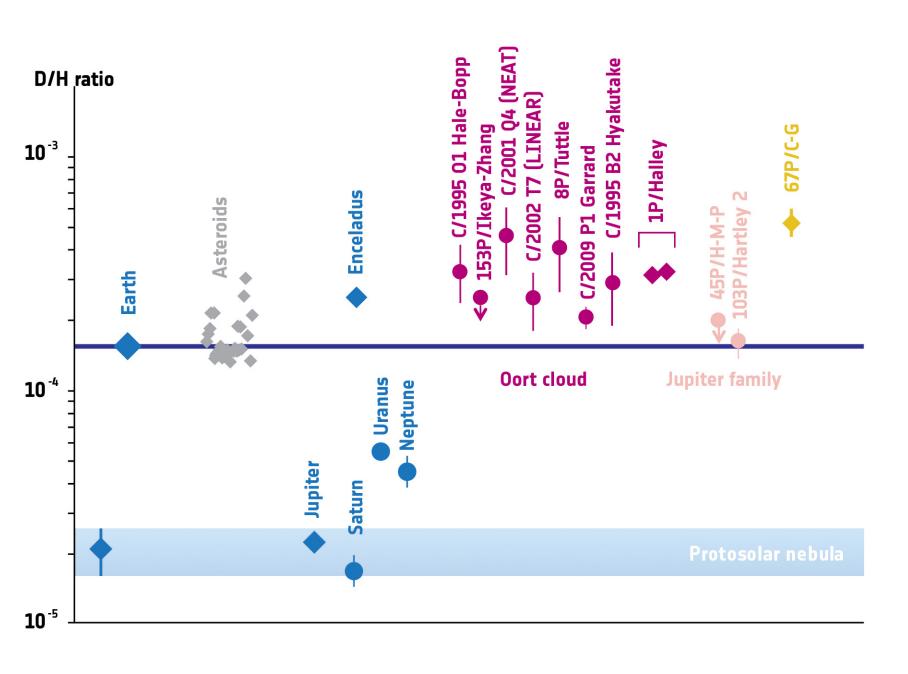

Heavy hydrogen is uncommon: on Earth, only about 1 in 10,000 atoms is the heavy variety. That's similar to the ratio of heavy-to-ordinary hydrogen on some asteroids. Some comets, on the other hand, have a larger fraction of deuterium -- 2 to 4 atoms per 10,000. Comet 67P, it turns out, has about 5 atoms of heavy hydrogen per 10,000 atoms: about four times as many as in the oceans on Earth.

This suggests that the water in Earth's oceans -- which we believe probably did originate in bodies which crashed into the early, very hot, very dry Earth -- did not come from comets like 67P.

Image courtesy of

Kathrin Altwegg et al. 2014

But don't forget: the comet, and Rosetta, and Philae, are all heading toward the Sun: they will reach their closest approach in August, 2015.

As the Sun draws near, the temperature of the comet -- and the Philae lander -- will increase. In addition, the strength of sunlight striking the solar panels on Philae will also increase. It is possible that the lander will "wake up" at some point and start to communicate with Rosetta again. Scientists may yet have a chance to carry out some of the experiments they have been planning for years ....

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.