Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

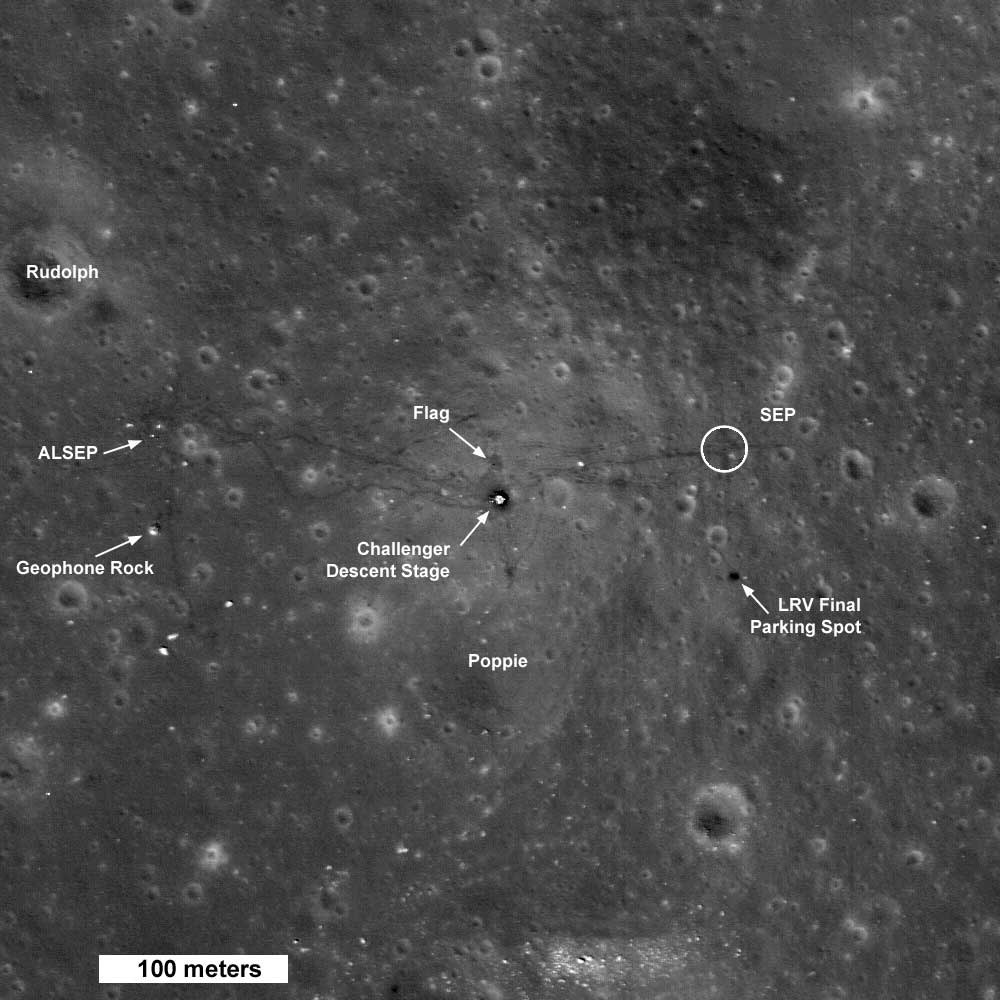

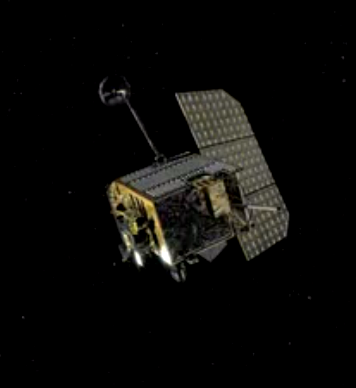

On June 18, 2009, NASA launched the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO for short), a satellite designed to study the Moon from an orbit about 50 km above its surface.

LRO has already acquired some high-resolution images of the lunar surface, and will continue to operate for at least another year or so.

However, the vehicle which launched LRO carried a second passenger, the Lunar CRater Observing and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS). This mission was designed, in part, to give LRO a very interesting target. The goal of LCROSS was to smash an object into the depths of a crater in permanent shadow, so that the debris would rise up out of the shadow and become visible briefly. If there should be any water ice hidden in those dark depths, this mission might reveal it.

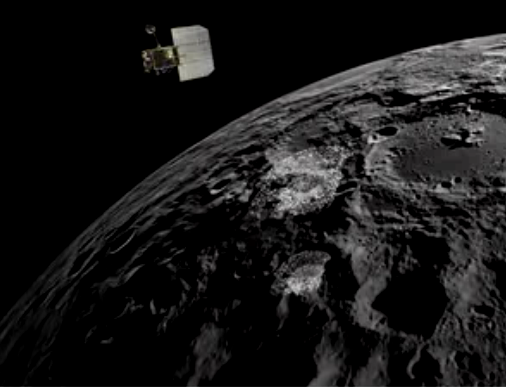

The upper stage of the LRO launch vehicle carried LRO into space.

Then LRO separated from the upper stage ....

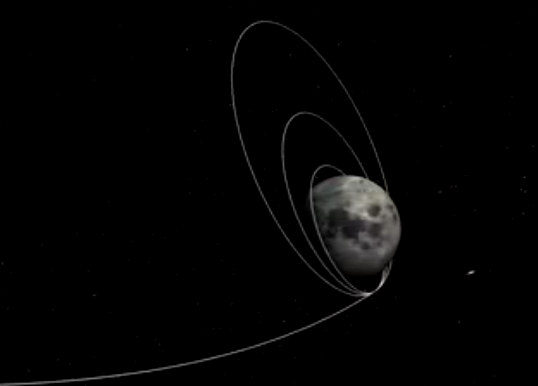

... and gradually made its way into low-Moon orbit.

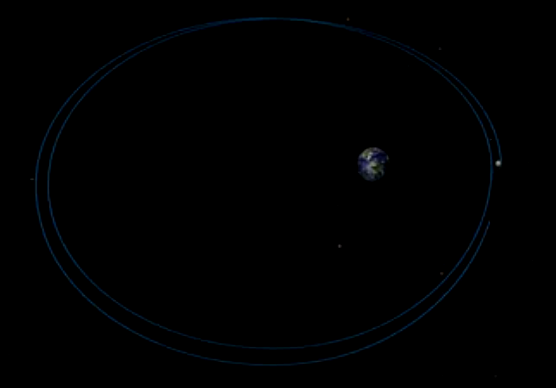

The upper stage, on the other hand, used the lunar gravity (and its remaining fuel) to enter a big, 40-day orbit around the Earth and Moon. After two circuits, the spacecraft headed straight for the South Polar region of the Moon.

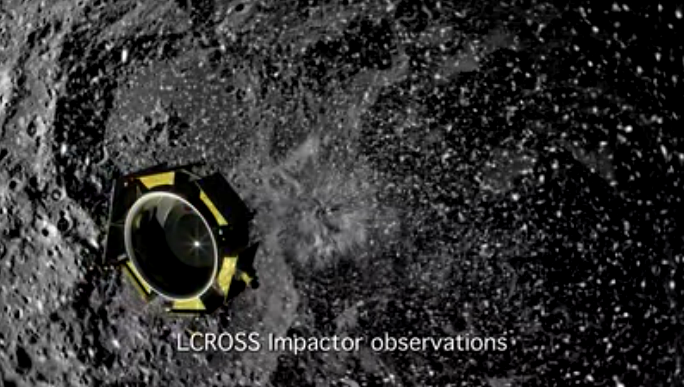

A few hours before the impact, the small LCROSS "shepherding spacecraft" left the upper stage.

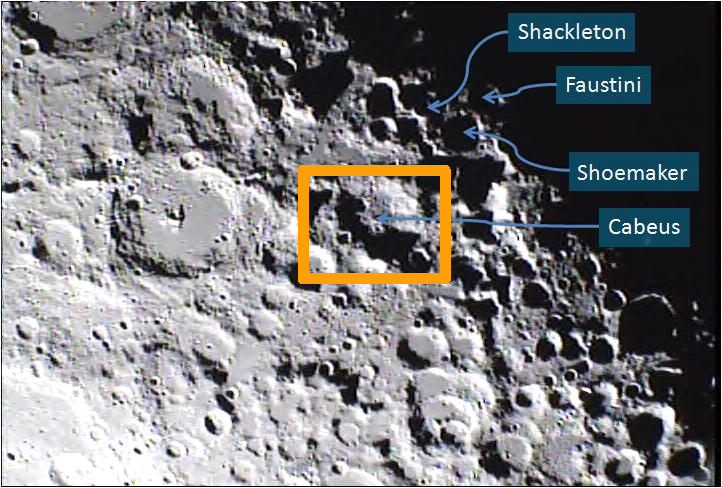

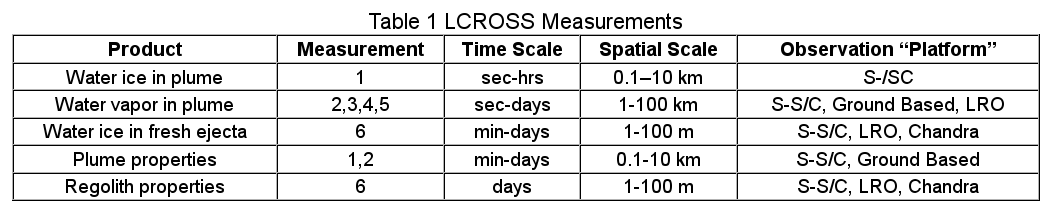

The Centaur upper stage (or "Impactor") led the way as the two items fell down to the lunar surface. Mission control chose the crater called "Cabeus" as the target, since a portion of this crater is always hidden from the Sun.

The impact of the Centaur upper stage, at a speed of around 6000 mph (or about 2500 m/s), threw up a plume of material. The "shepherding spacecraft" had a few minutes to study the region before it, too, struck the surface.

All the while, the LRO spacecraft would be watching from its orbit 50 km above.

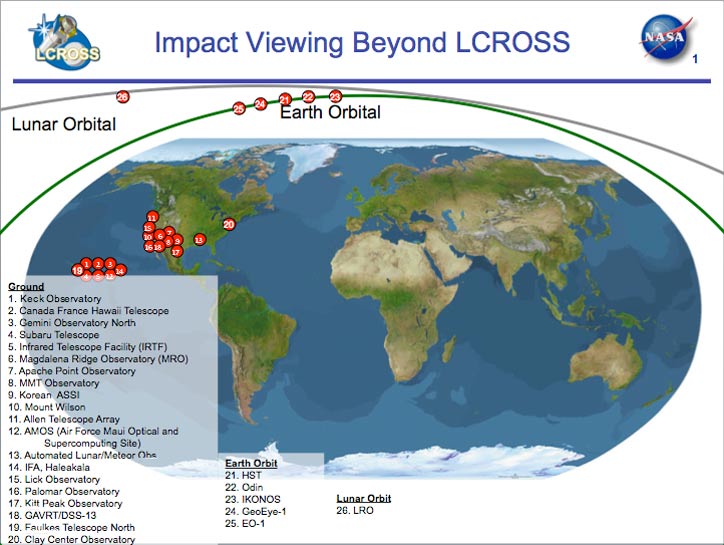

Scientists aimed other space telescopes (among them, HST) and Earth-based instruments at this site as well.

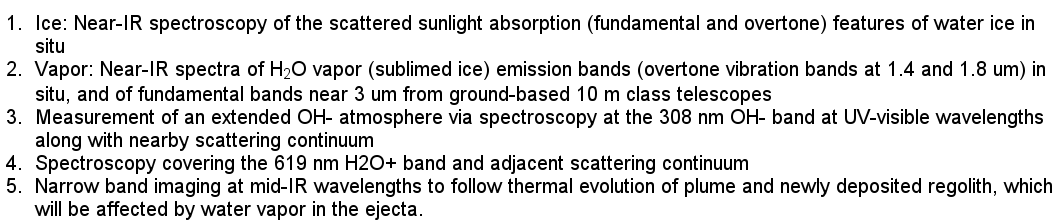

If all went well, material in the ejecta could be studied in many ways:

The short answer is "not very much." That's not really a fair answer, since reports from the main instrument teams have NOT yet been released as of this writing (Nov 5, 2009). I believe that those reports will be made public within a few weeks or months. The LCROSS web site states

The science team is now preparing to present more at the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (LEAG) meeting to be held in Houston, TX, Nov 15-19, 2009 and submit results for peer review.

However, what is clear is that the plume of material thrown up by the crash of the Centaur was not nearly as large or as bright as some had calculated, or as everyone had hoped. Let me re-orient the overview of the Cabeus crater:

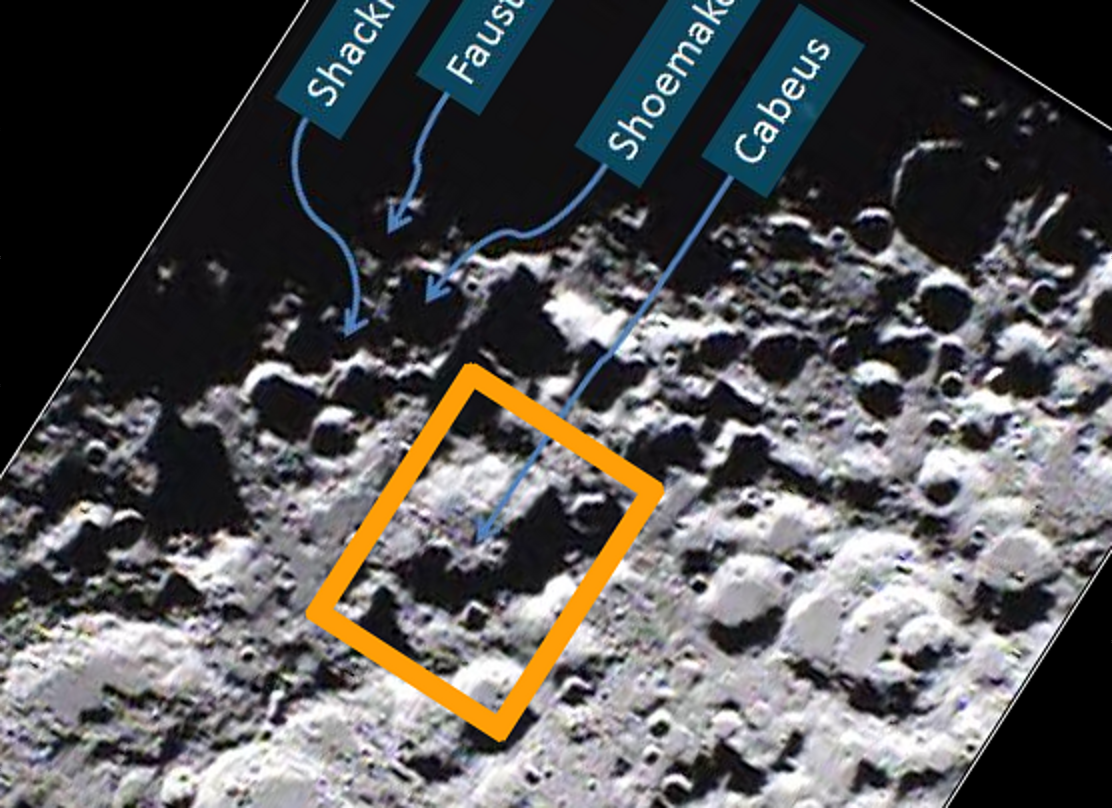

The LCROSS shepherding spacecraft did detect a faint glow in the mid-infrared due to heat generated in the impact.

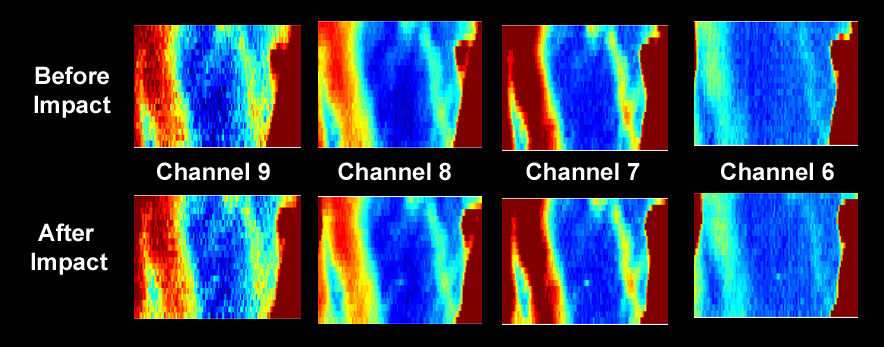

The LRO satellite, flying high above, also detected heat from the impact, using its thermal infrared mapping instrument. The "before" images were taken two hours before impact, and the "after" images 90 seconds after impact.

The real key to confirming (or rejecting) the presence of water in the ejecta is spectroscopy. Unfortunately, none of the spectroscopic data from the spacecraft has been released yet, as far as I can tell. Here are a few comments from Bruce Betts, an astronomer who used the Palomar 200-inch telescope to watch the impact:

Despite beautiful adaptive optics near-IR imaging from Palomar 200 inch, no plume visible, at least not obvious. ... Well, a really fun & interesting night at Palomar, despite the distinct lack of plume-age. Amazine scope and adaptive optics and sensors. ... My sleepy LCROSS summary: no plume, saw thermal flash and thermal crater, got some spectra. Analyses to come in future.

I guess we'll just have to wait for the official release of the technical reports.

Note added Oct 21, 2010:

The first papers have been released! See Planetary Society blog entry entry for Oct 21, 2010 for an overview and for links to the papers in 'Science' magazine.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.