- Universal Time is good for keeping everyone synchronized, no matter where she lives. If you are trying to describe the exact moment when one star began to eclipse another, you don't want to get caught up in time zones.

- Local Sidereal Time is a clock which follows the stars, not the Sun. If I want to know if the Andromeda Galaxy is high above the horizon right now, just tell me the LST.

- Julian Date

counts time in days, rather than in hours or seconds

or minutes. Moreover, it has a starting point --

a time when the JD = 0 -- far, far in the past,

long before any written astronomical records.

That means that just about every astronomical

event will have a positive date, and THAT makes

it very simple to compute the time between two events.

Quick: how many days was it between these two events?

Athletics win World Series Oct 26, 1911 Titanic sinks April 15, 1912 ---------------------------------------------- time between =Not so easy, is it? Try again with Julian Dates:

Athletics win World Series 2,419,335 Titanic sinks 2,419,507 ---------------------------------------------- time between =

But astronomers have a much broader span of time to cover -- the entire history of the universe. You'll hear them use these terms:

- megayears are a convenient unit for discussions of motions of stars in a galaxy, or the lives of massive stars.

- gigayears are a convenient unit for discussions of the lives of stars like the Sun, or galaxies, or the universe.

- Hubble time refers to the expanding universe. One Hubble time is roughly the time it would take for two distant objects to double their current separation, if they continued to move apart at their current rate.

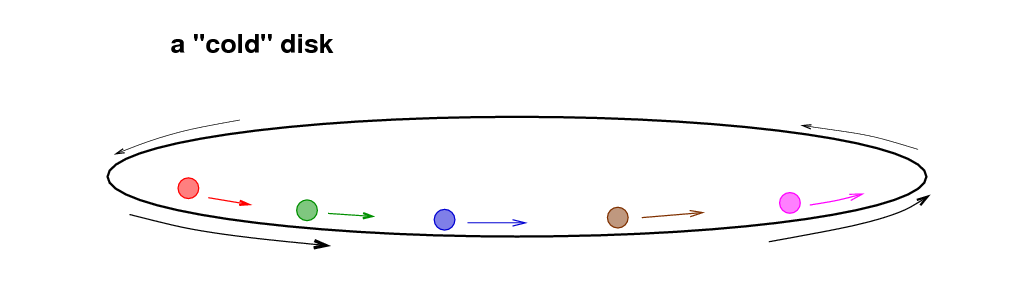

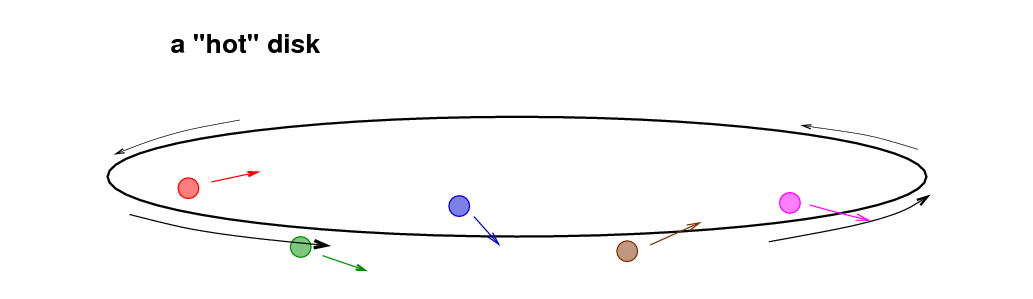

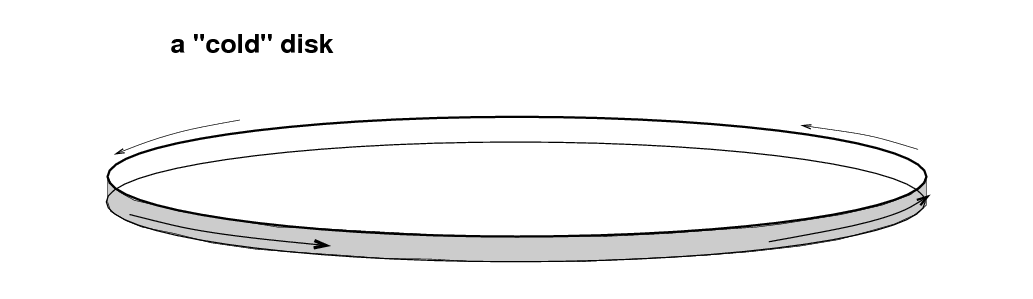

- crossing time

is the time it takes for an object to move

from one side of its orbit to the other.

Q: What is the crossing time of Jupiter?

- relaxation time has nothing to do with Jimmy Buffet, alas. It describes the time it takes for objects in a cluster (could be a cluster of stars, or a cluster of galaxies) to swap energy with each other enough times to homogenize the group's orbits.

Space is big. You just won't believe how vastly, hugely, mind- bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it's a long way down the road to the chemist's, but that's just peanuts to space.

Q: Who wrote this?

the answer

As a result, astronomers have devised a set of units which are reasonably well matched to commonly encounted distances in space. Among them are the

- parsec: a typical distance between stars in our galaxy

- kiloparsec: roughly the size of a small galaxy, or the distance between arms in a big galaxy

- megaparsec: roughly the separation between galaxies

Why don't astronomers use light-years? Well, the light-year is roughly the same size as the parsec, and if we used both, we'd have to remember how many light-years are in one parsec (and vice versa). Remembering is hard, so we don't bother.

Sometimes, astronomers describe the distance to an object in an indirect manner. There are good reasons for the following approaches, but it can be really frustrating at first glance.

- distance modulus (m - M)

is an indirect way to express the distance to an object.

The absolute magnitude M is the magnitude an object

would have if we placed it exactly 10 parsecs

away from the Earth.

The apparent magnitude m is the magnitude that

we actually measure.

For example, consider two Sun-like stars, which produce exactly the same amount of light, and hence the same absolute magnitude M = 4.34 . Alpha Centauri is our closest stellar neighbor, and so appears very bright in our sky; HD 6818, which is much farther away, appears too faint to see without a telescope.

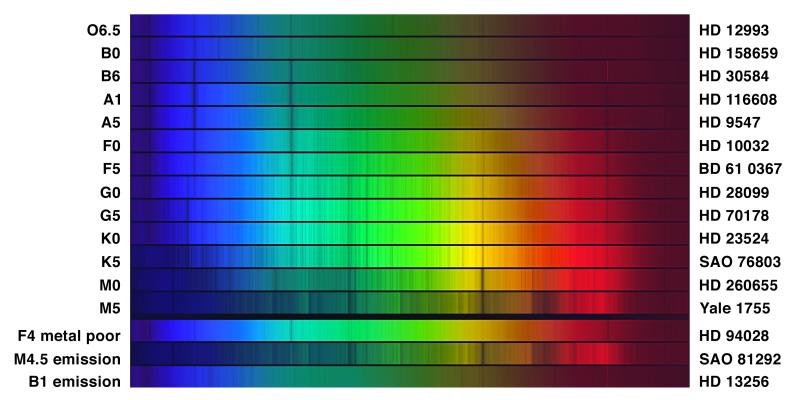

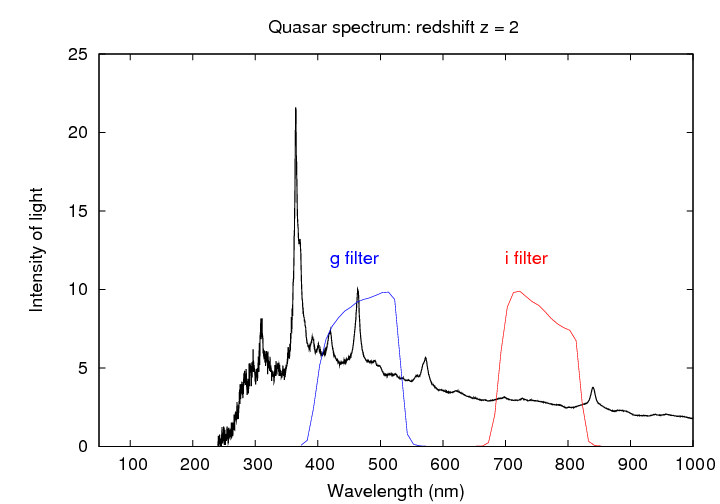

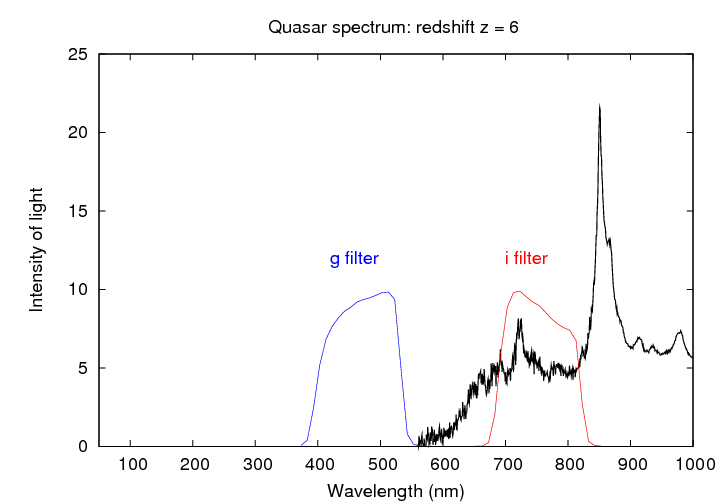

Name Abs mag M distance (pc) App mag m (m - M) Alpha Cen 4.34 1.34 -0.01 -4.35 HD 6818 4.34 101.3 9.37 +5.03 - redshift is often used to describe the properties of very distant objects -- galaxies and quasars. We can actually measure redshift, based upon the appearance of absorption or emission lines in the spectrum of an object. Converting this measurement to a distance, however, depends on the model of the universe one adopts.

- solar masses

(by far the most common). Our Sun has a mass of 1 solar mass,

which is often written as a little circle with a dot in

the middle:

Most stars have masses between 0.01 and 100 solar masses, so this is a very convenient unit for individual stars.

Galaxies are made up of billions or trillions of stars, so one might expect astronomers to devise a unit like the "galactic mass" --- but we haven't. This is one case (see another below) in which astronomers do use scientific notation. When we write the mass of the Milky Way or the Andromeda Galaxy, we end up with something like 1012 solar masses.

- Earth masses and Jupiter masses

when discussing planets.

Ten years ago, when the only planets we could

detect were very massive,

the standard was Jupiter masses,

In recent years, as our ability to detect smaller planets -- and the amount of $$ available to study them -- has increased, astronomers more and more often talk about Earth masses:

The Milky Way Galaxy, for example, has a luminosity of

roughly 200 billion

![]() .

.

Why don't astronomers create a unit which represents the luminosity of an entire galaxy? If they did, they wouldn't have to keep including factors like 1011 when talking about galaxies, or 1013 when talking about quasars.

Why don't they? Beats me.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.