Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Optical Telescopes II: Refractors

In the late 1800s, the refractor was King:

the largest telescopes in the world were the

36-inch at Lick Observatory

and the

40-inch at Yerkes.

But around the turn of the century,

astronomers decided that they needed as much

light-gathering power as possible in order

to measure spectra and detect faint stars

and galaxies on photographic plates.

Reflectors could be made larger than refractors,

so the tide turned, and

mirrors with larger and larger diameters

took over.

George Ellery Hale

was the driving force

behind the construction of a series of

very influential instruments:

For most of the twentieth century,

refractors fell out of the mainstream of

professional astronomical research.

But in the past 20 to 30 years,

they have made a strong resurgence,

as a result of three factors:

- exoplanets

- You've heard about exoplanets, right?

They have been a pretty hot commodity in the

astronomical community since

the first exoplanet was found in 1995.

One of the cheapest and most efficient ways to

find (and characterize) exoplanets is via

the transit method.

All it takes is the ability to measure the light from a star

to a tenth of a percent or so (in other words,

to the millimag level).

But since there are so many stars in the sky,

in order to find the rare transit events,

one must measure thousands or tens of thousands

of stars at a time.

Which brings us to ...

- (automated) wide-area surveys

-

There are a LOT of stars in the sky: in rough numbers,

| Mag |

Approx. Number of stars |

| 5 |

2000 |

| 6 |

6000 |

| 7 |

18,000 |

| 8 |

52,000 |

| 9 |

190,000 |

| 10 |

450,000 |

| 11 |

1,300,000 |

Q: Where can one find these numbers?

A: Try the "Search" tab at the Gaia Archive

In order to check them all for exoplanets -- or for

other interesting properties --

it makes sense to use an instrument which has a

wide field of view,

so that you can measure hundreds or thousands

of stars in a single image.

The same is true if one is searching for

rare transient events,

such as GRBs, SNe, or the optical counterparts to

gravitational wave sources.

Starting in the late 1980s,

astronomers started to combine wide-field telescopes,

electronic cameras,

and computer-controlled motors in order

to carry out surveys of large sections of the sky

in an automated manner.

I enjoyed

dabbling in the early days of automating telescopes

myself ...

- professional sports

-

A connection between football and astronomy?

Sports Illustrated cover for Jan 24, 2011

Yes!

Photographers who cover sports need lenses with two

key properties:

- long focal length (to bring the action close)

- small focal ratio (to put lots of light in each pixel

and enable short exposure times)

Well, these are exactly the same major concerns of

astronomers.

But since there are many more professional sports photographers

than astronomers, and since their newspapers and

magazines and websites will pay them well to get

good pictures,

some of the major lens makers have created

lenses which meet these needs and are not

too expensive.

This article

might give you some idea for the lenses

commericially available.

Q: What are the typical prices for these lenses?

Let's go through one example to see how this works.

We begin with a lens, of diameter D

and focal length L.

The focal ratio of the lens is

On the other end of the camera is a detector

with pixels.

The relationship between a pixel's physical size p

and its angular size α on the image plane

is simply

Now, some typical numbers for astronomical instruments of interest,

as you will see eventually,

are

- CCD pixel size is typically p = 10 microns

- telescope diameter might be D = 4 inches = 100 mm

That might sound like a small telescope, but it's a pretty

darn big lens.

One can use this information to compute the angle subtended by

pixels in a telescope, and the solid angle covered by each pixel.

Lens Diam D focal ratio focal length pix ang size pix ang area

(mm) f L (mm) (arcsec) (sq. arcsec)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

100 2.5 250 8.25 68.07

100 5 500 4.12 17.02

100 10 1000 2.06 4.25

100 15 1500 1.38 1.89

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

So, in general,

- short focal lengths correspond to big pixels on the sky

- long focal lengths correspond to small pixels on the sky

Q: Which is better: a short focal length, or a long focal length?

Well, the only real answer is "It depends on what you are trying to do."

For example,

suppose you are trying to make the best measurements possible

of the BRIGHTNESS of some stars.

We'll discuss this in a future lecture, but one way to compute

the signal-to-noise ratio in the measurement of a star with

an electronic detector looks like this:

where

N(star) is the number of electrons from the star

which fall within the aperture

N(backpp) is the number of electrons Per Pixel

due to the sky background

N(thermpp) is the number of electrons Per Pixel

due to thermal effects

R is the readout noise per pixel, in electrons

npix is the number of pixels in the aperture

In certain situations,

the limiting factor in the measurements becomes the noise due to

background or thermal effects in the detector.

In such cases,

spreading the light from a star over a large number of pixels

will lead to a larger amount of noise.

So, in SOME situations,

a larger focal ratio,

and longer focal length,

creates much smaller pixels,

spreading out the light from an object over many pixels.

If we are fighting against sources

of noise --

such as background light or readout noise

or dark current --

which affect each pixel independently,

then we will lose the

signal-to-noise battle as the light of our target

is spread out over many pixels.

In other words,

a short focal ratio

means big pixels,

and, in SOME situations, big pixels mean

a higher signal-to-noise ratio in short exposures.

Q: What happens if we make the focal ratio _too_ small,

and the pixels get _too_ big?

Yes, if the pixels are so large that they cause

neighboring stars to blend together,

we won't be able to measure the light of each star properly.

In an ideal case, astronomers who want to detect and measure

one particular type of celestial object can design

a set of lenses and detectors which provide the best

signal-to-noise ratio for their project.

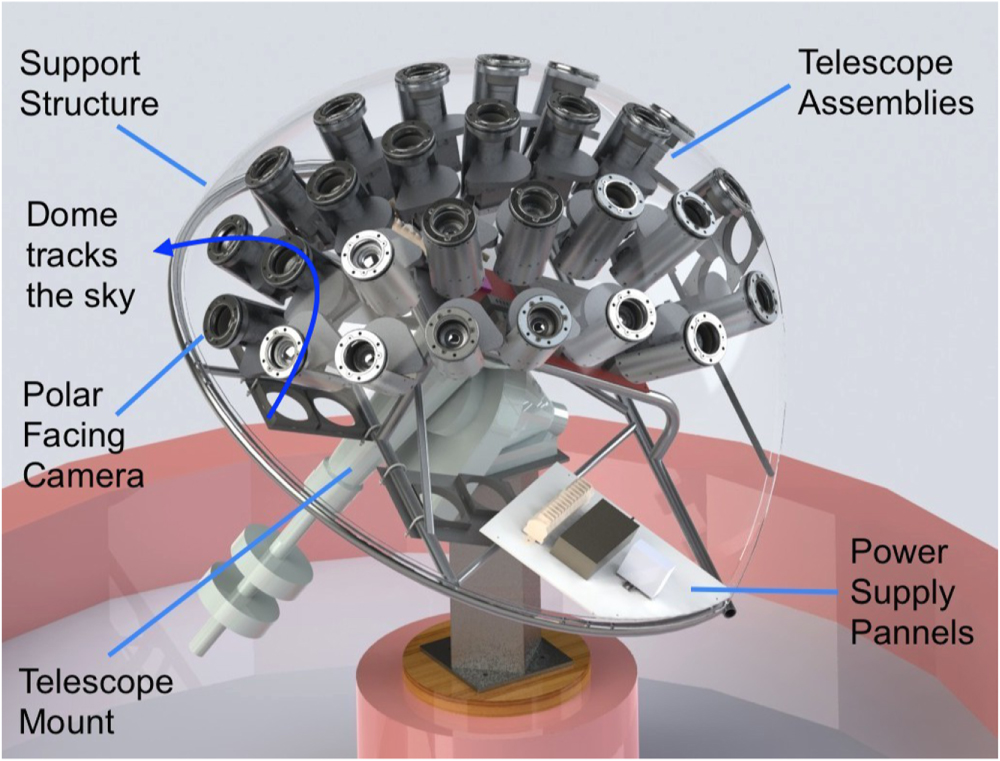

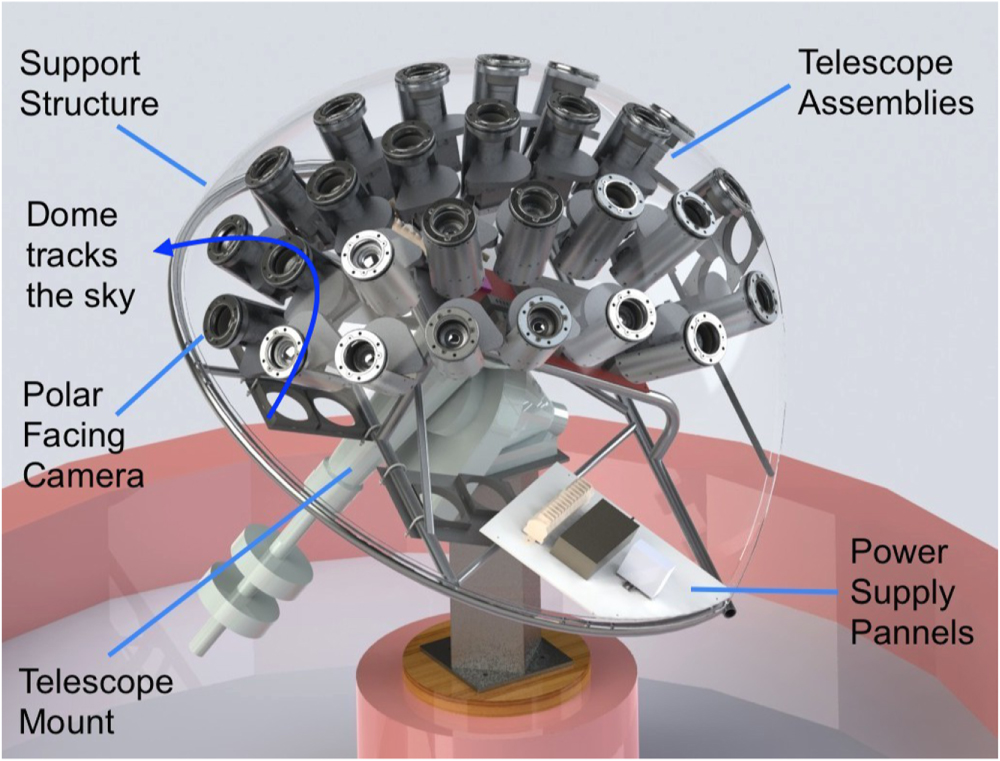

One ambitious project uses a LOT of small refracting telescopes

to take pictures of (almost) the entire sky, all at once.

The first phase of this project was based on

Evryscope:

- 23 camera lenses with 85 mm focal length at f/1.4

- each detector covers an area of about 24x16 degrees

- all placed on a single equatorial mount to track the stars

- a single "snapshot" covers roughly 8000 square degrees

Figure 2 taken from

Ratzloff, J. K., et al., PASP 131, 075001 (2019)

Figure 1 taken from

Ratzloff, J. K., et al., PASP 131, 075001 (2019)

One attractive feature of the device is its relatively low cost.

For example, the optics are all available off-the-shelf.

Q: How much does each of the Evryscope's camera lenses cost?

(look for Canon 85 mm f/1.4)

Q: How many lenses does the Evryscope have?

Q: What's the total "optics" cost?

The main science goal is to detect

relatively bright transient and variable

objects.

The key here is to cover a LARGE AREA on the sky.

The scientists running Evryscope recently published a paper

describing the results of one small region of the southern

sky, after only about 8 months of observations:

The scientists who built Evryscope have now moved

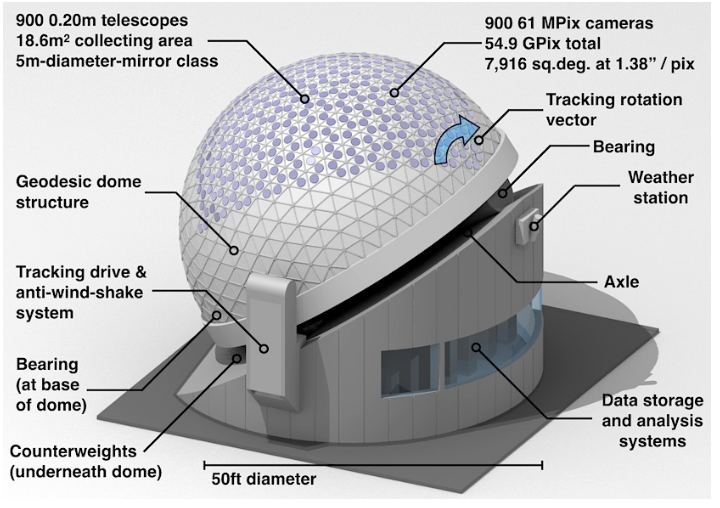

to a larger, more sophisticated instrument:

ARGUS.

Figure 1 taken from

Law, N. M., et al., PASP, 134, 035003 (2022)

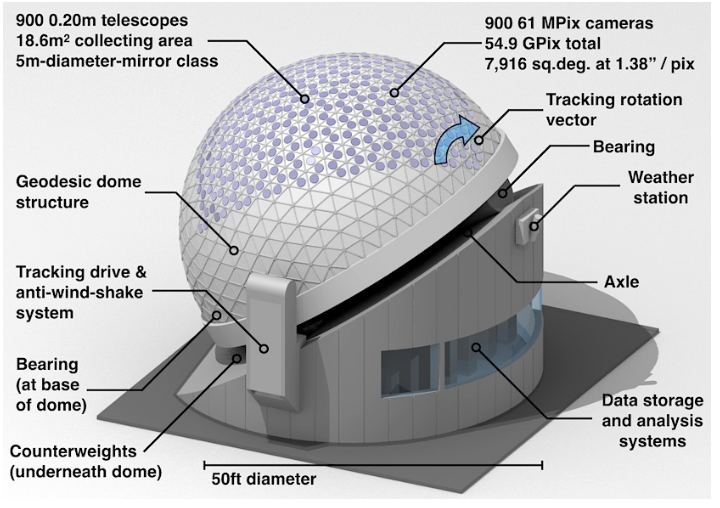

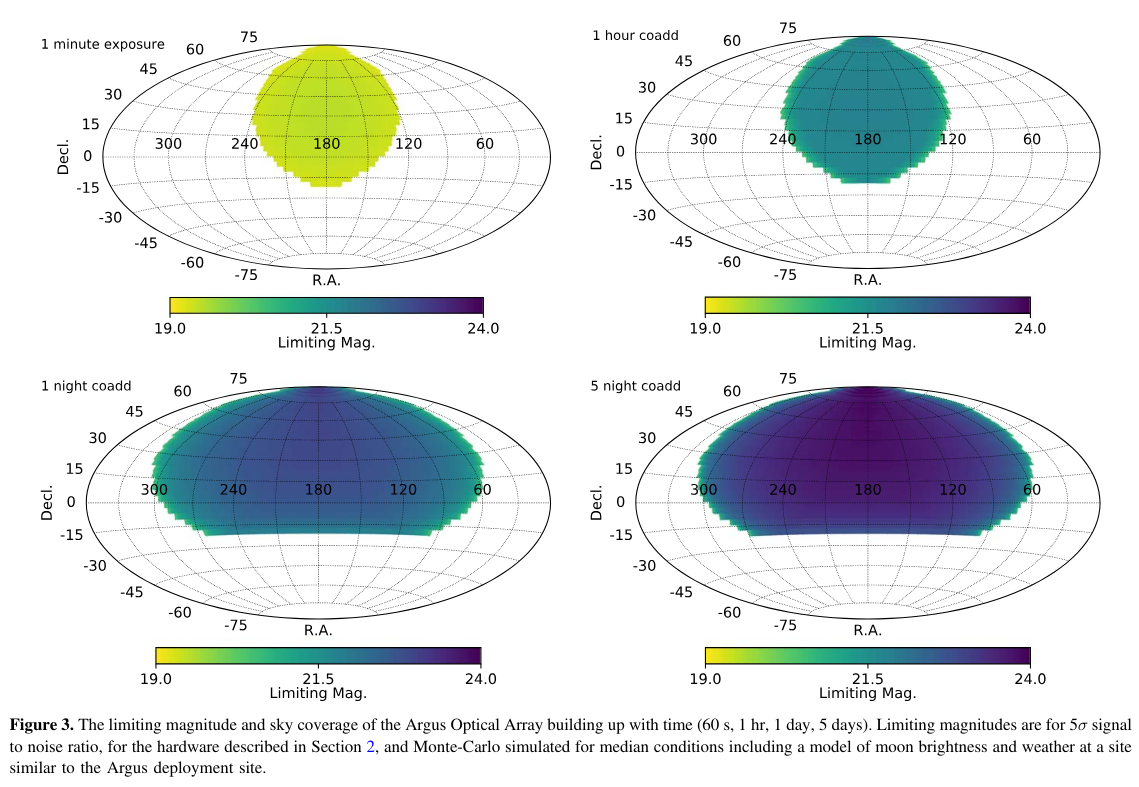

This combination of telescopes and detectors will be able

to reach much fainter stars.

By coadding images over the course of a night,

Argus may be able to measure stars of magnitude 24!

Figure 3 taken from

Law, N. M., et al., PASP, 134, 035003 (2022)

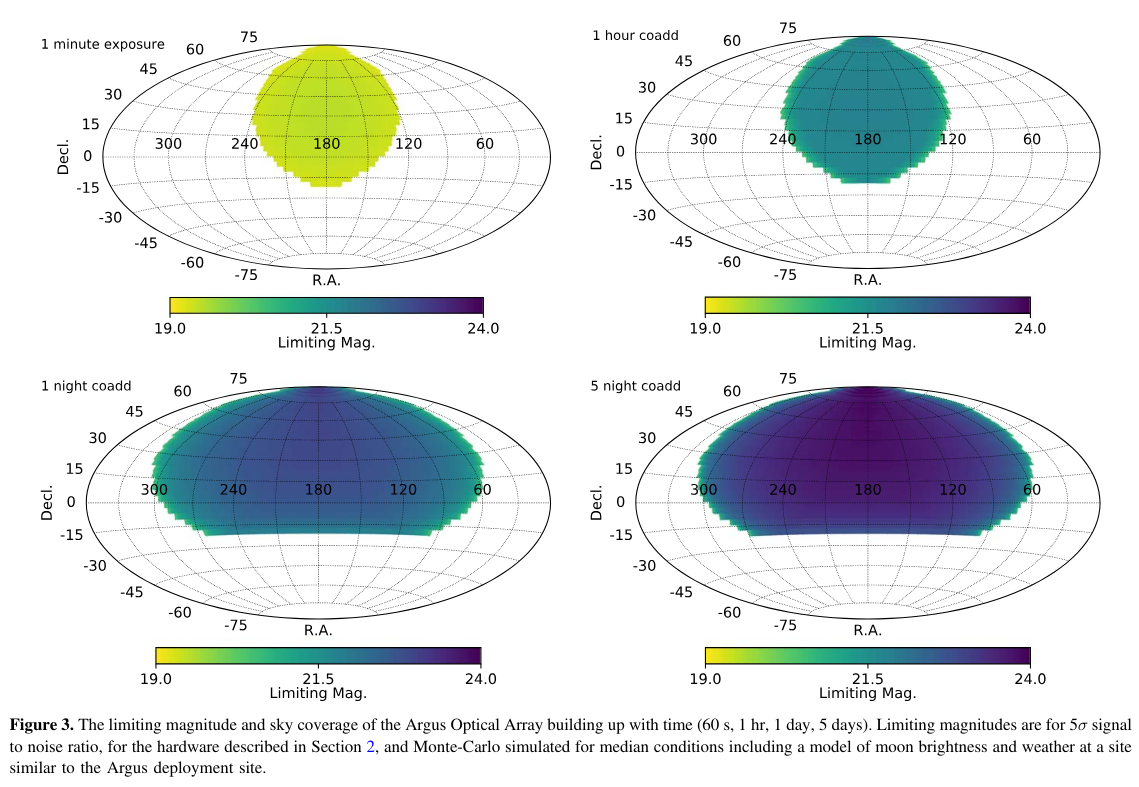

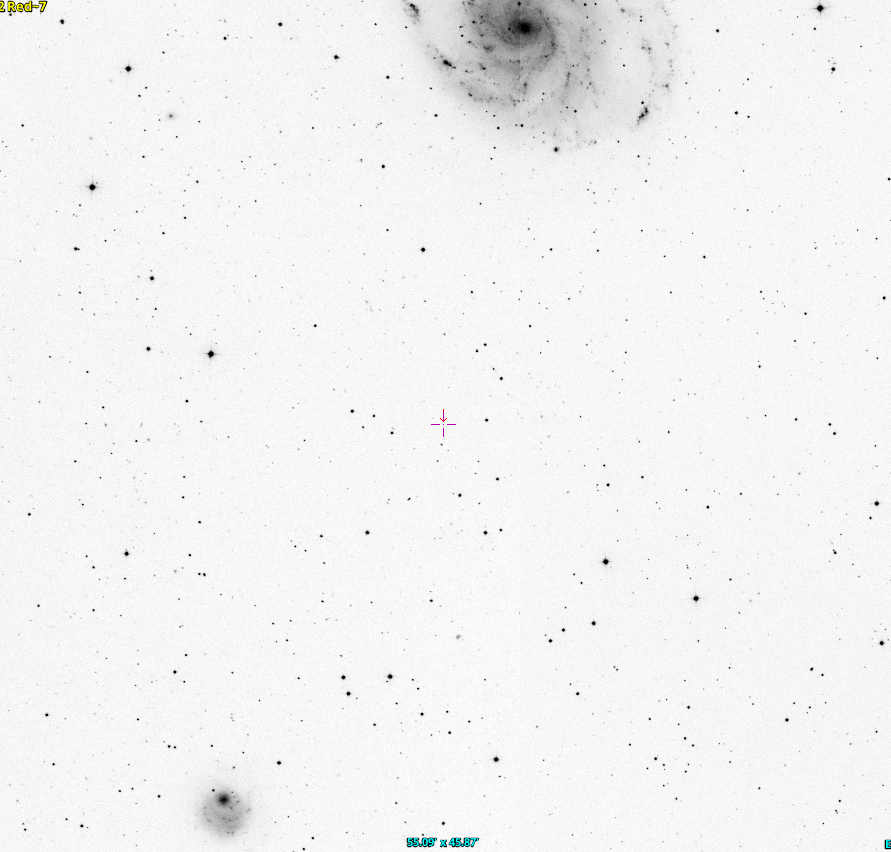

Another new refractor-based instrument has a different goal:

detecting low-surface brightness galaxies.

These are galaxies in which the starlight is spread out over

a large area on the sky, which makes them blend into the

background sky brightness.

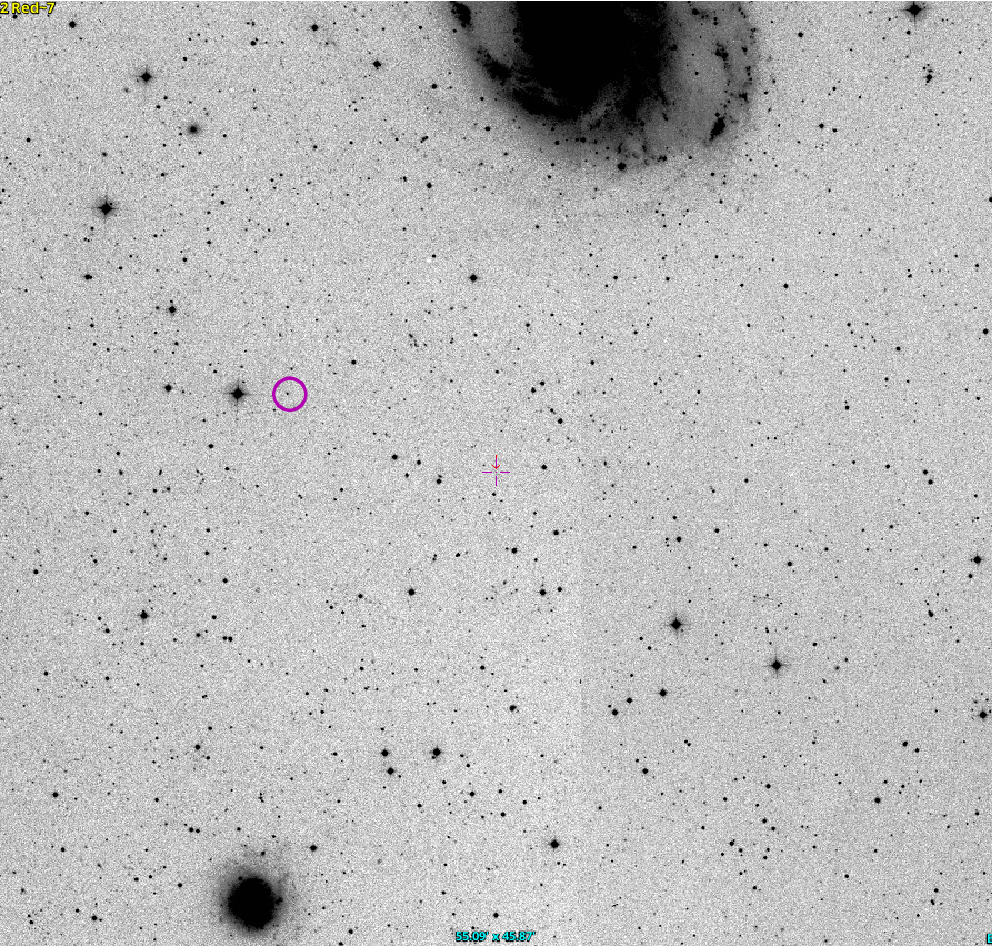

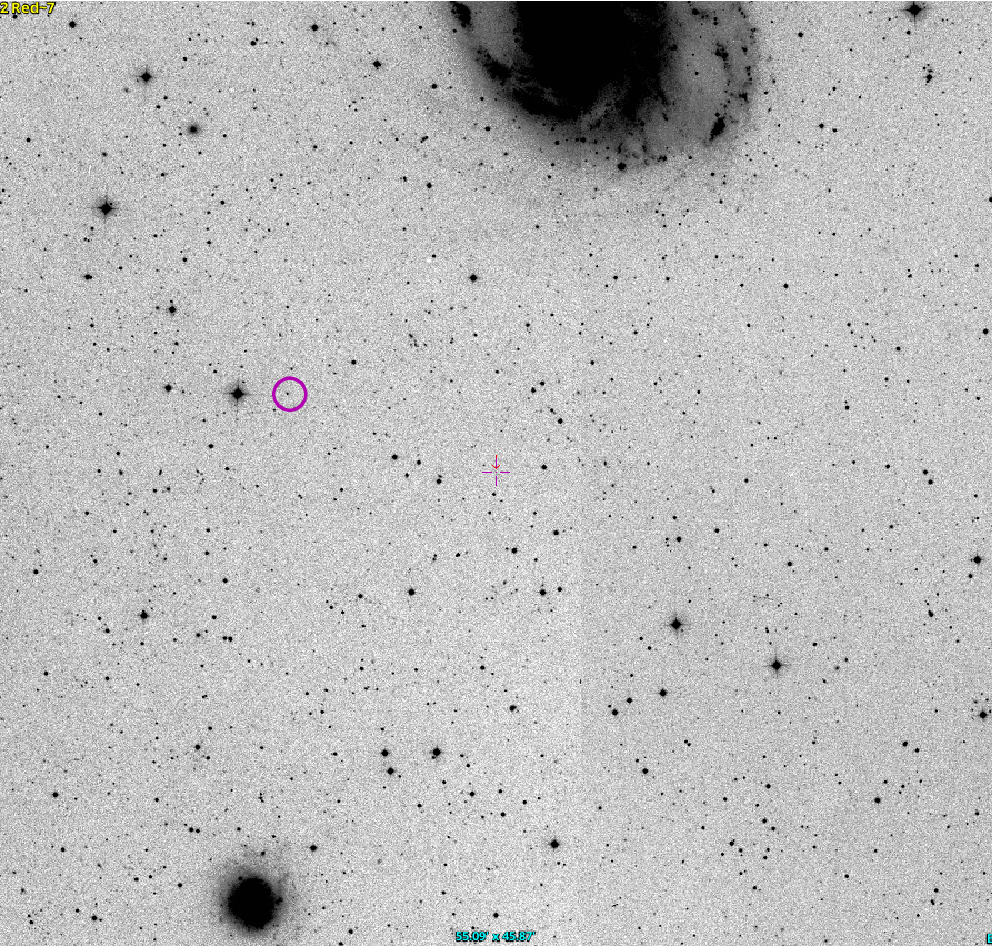

For example, consider this region near the big, bright, spiral

galaxy M101.

The crosshairs are at location

RA = 14:03:49.4 Dec = +53:59:20

Do you see a galaxy somewhere NEAR the crosshairs?

Perhaps you could use

AladinLite

to look for it.

Here, I'll help. This is the same region of the sky,

but with the contrast increased.

I'll also circle a star which has roughly the same magnitude

as the galaxy we are seeking.

Do you see it now?

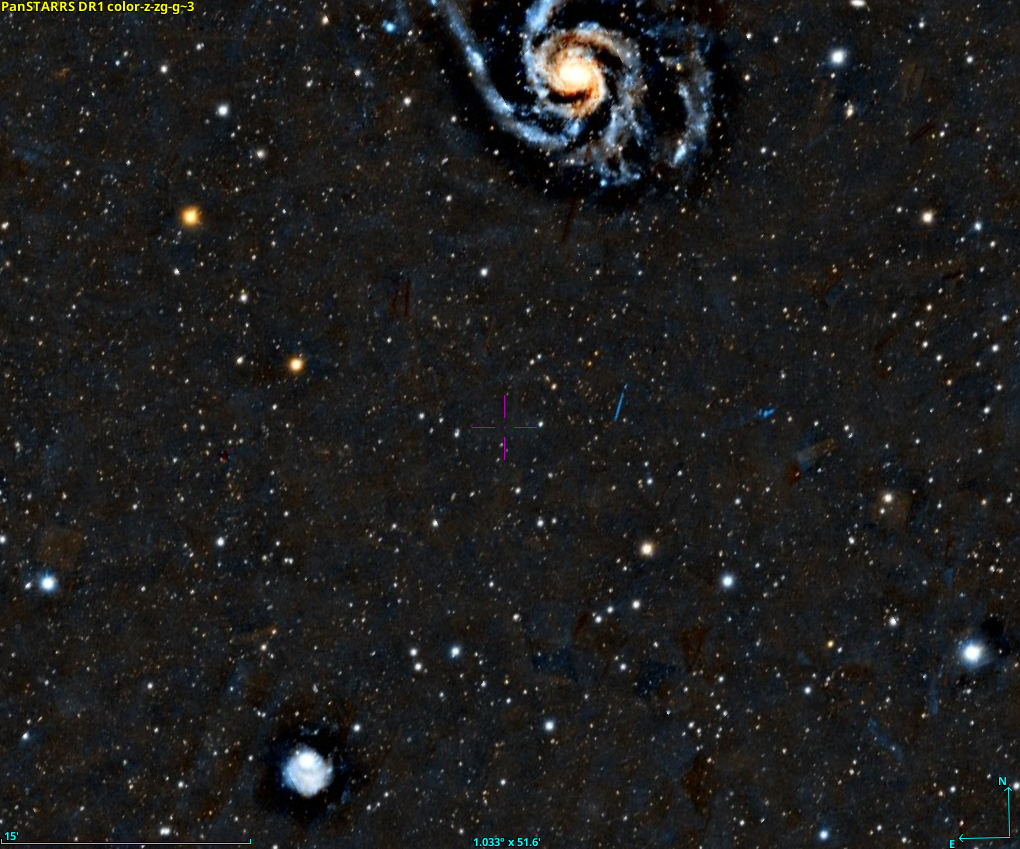

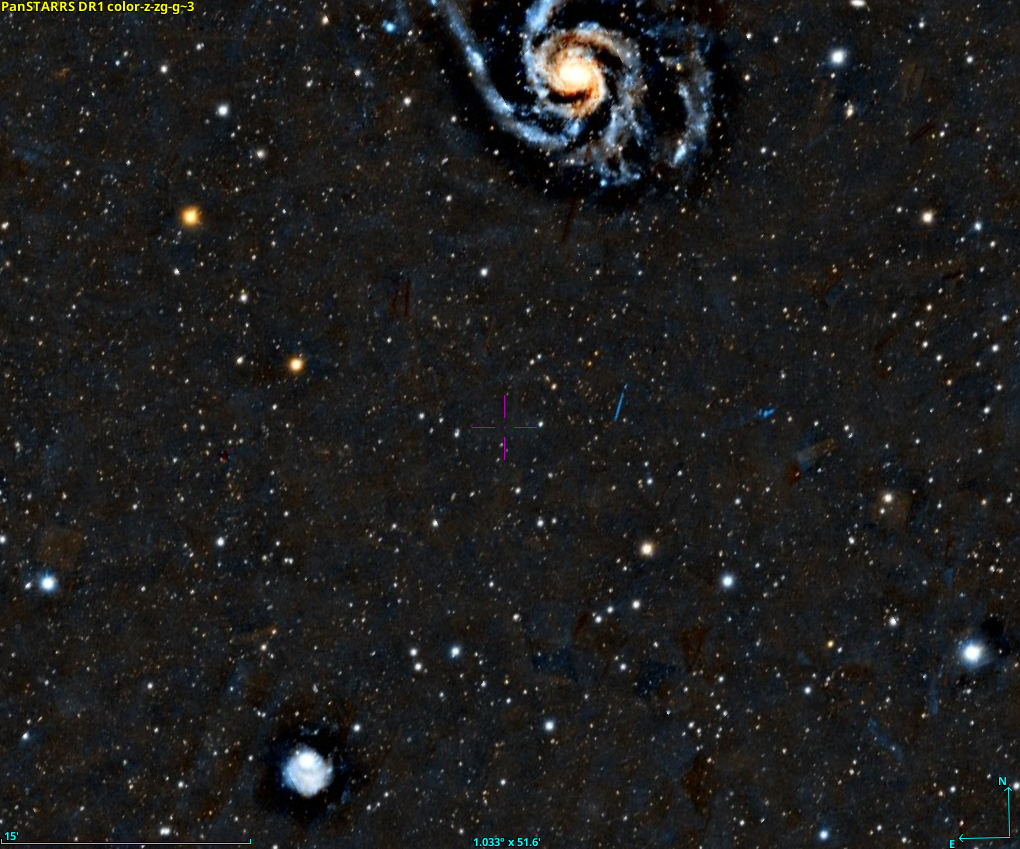

Here, let's try a color composite from the Pan-STARRS survey.

Does this help?

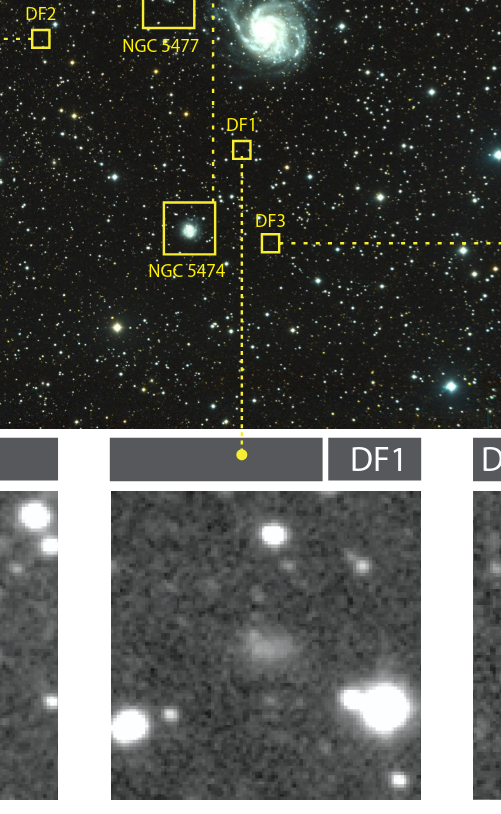

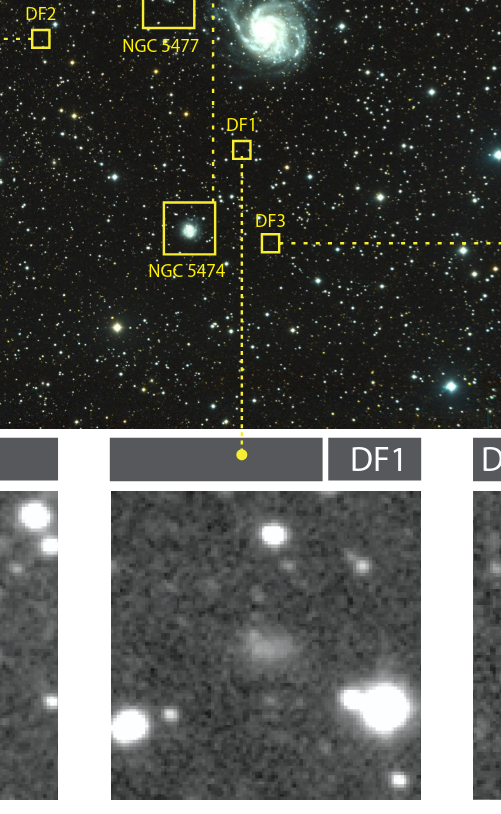

Well, if you can't find it, here's a chart

from the paper

The Dragonfly Nearby Galaxies Survey. III. The Luminosity Function of the M101 Group.

Note the box labelled "DF1" near the center of the figure,

just below the big galaxy M101.

There's a zoomed-in closeup at the bottom.

Taken from Figure 6 of

Danieli, S., et al., ApJ 837, 136 (2017)

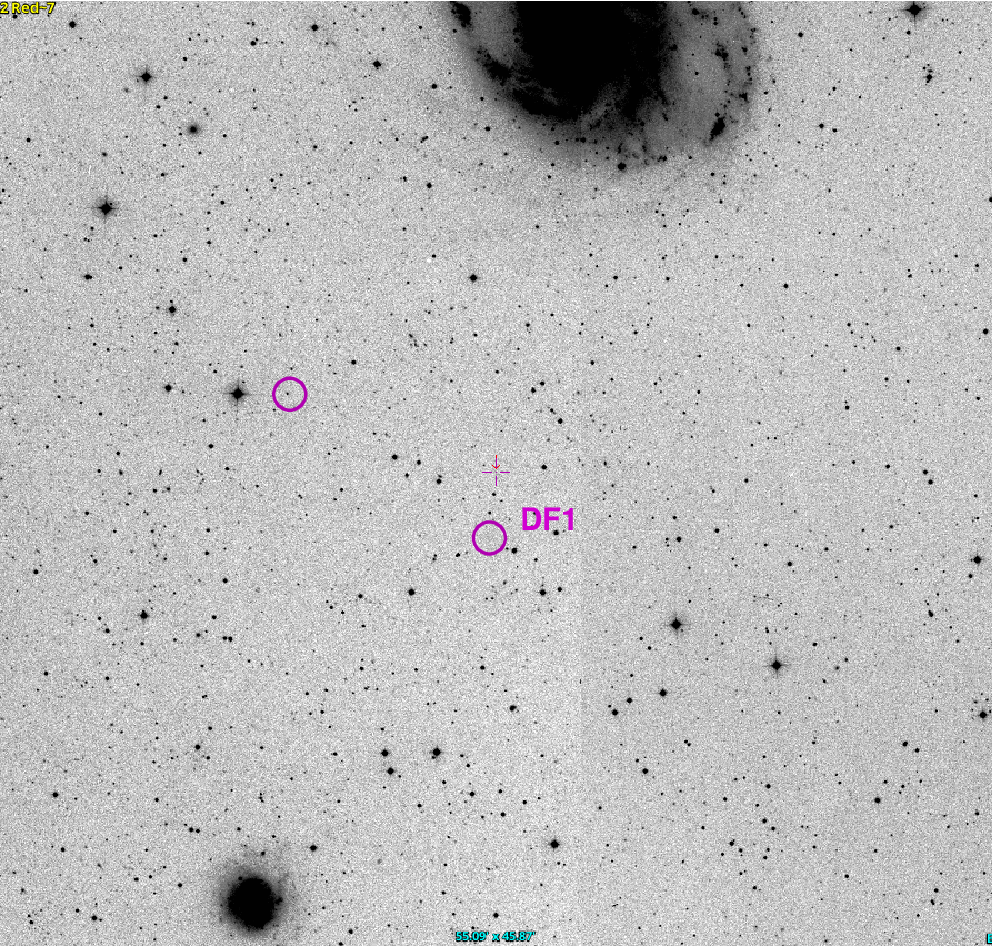

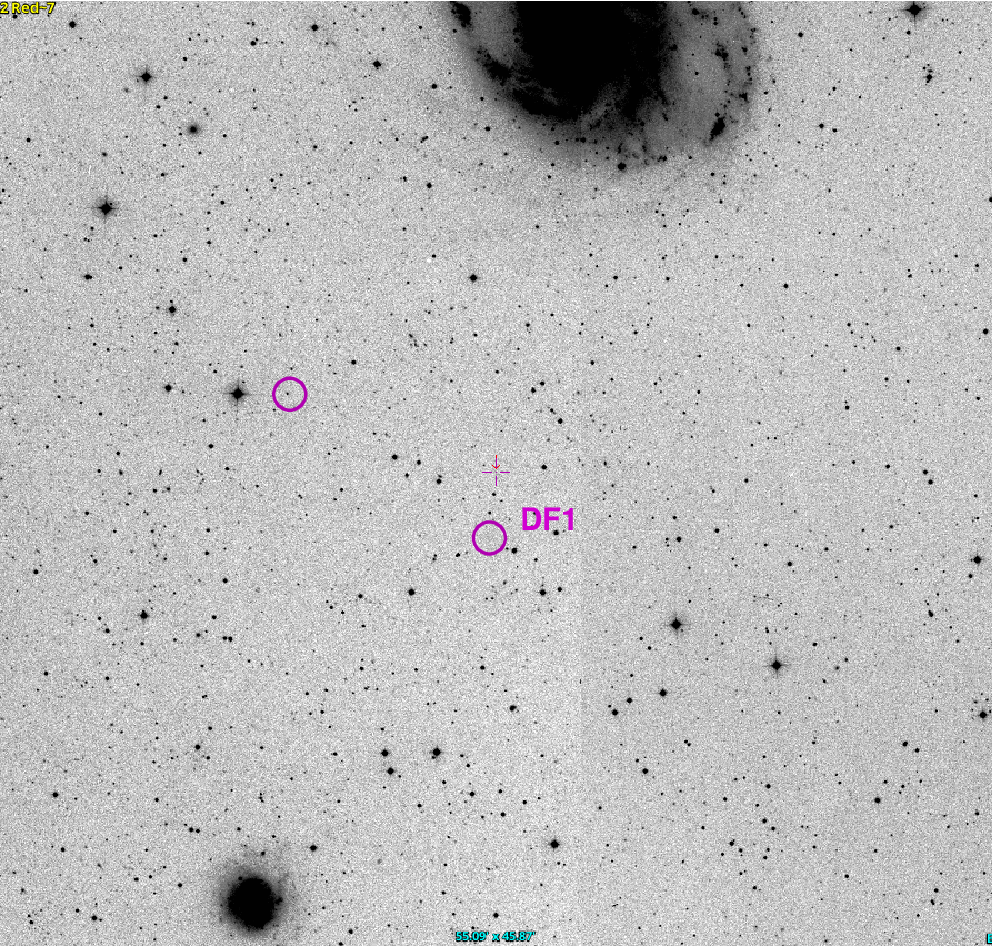

Here it is in the original DSS image:

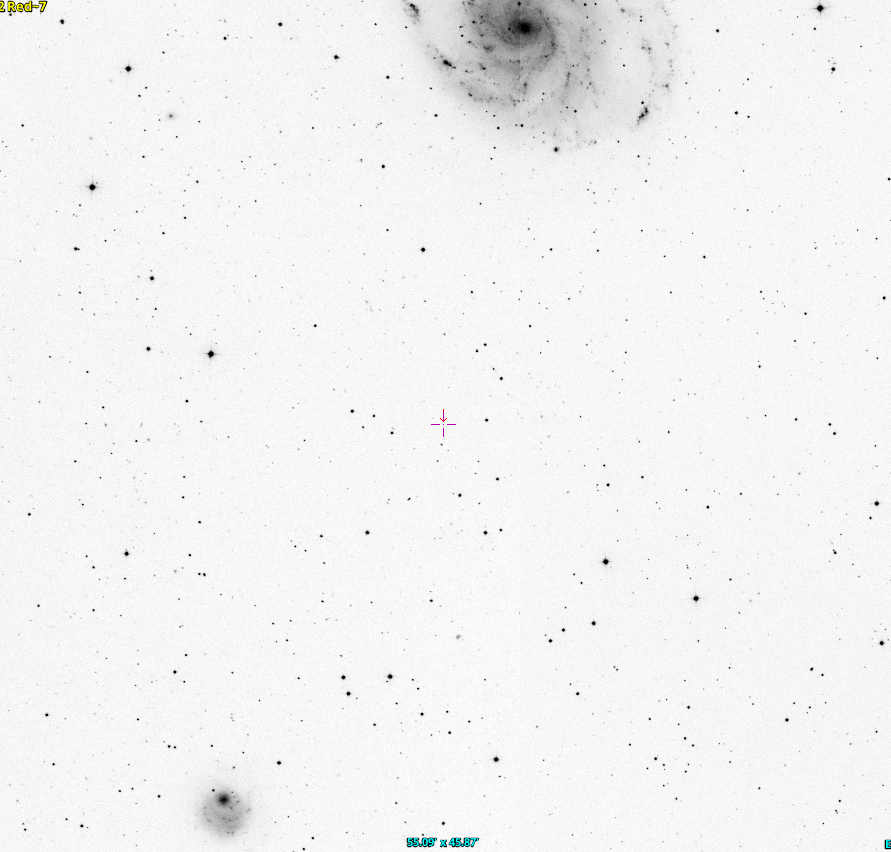

The challenge of detecting these objects with very low surface

brightness is to separate their light from that of the

background.

It turns out that using relatively large pixels helps:

the fewer pixels over which a galaxy's light is spread,

the smaller the contribution from readout noise and dark

current.

One must also perform very, very careful image reduction

and calibration.

The Dragonfly Array was designed to combine the images

taken by 10 telephoto camera lenses, all staring at the

same region of the sky.

Image courtesy of the

Dragonfly Telescope gallery

A later upgrade increased the number of lenses:

Image courtesy of the

Dragonfly Telescope gallery

This instrument has been so successful at finding

low-surface-brightness galaxies that

its builders

at the University of Toronto and Yale

have decided to help it morph into

MOTHRA!

Mothra appears courtesy of

Toho

Whoops, sorry. Wrong Mothra.

This is just PART of the new instrument --

one of 30 fork-mounted components.

Image courtesy of

Dragonfly Telescope website

Though the instrument is still under construction,

it promises to be a ... significant upgrade in

complexity and capabilities:

Dragonfly is evolving into the Modular Optical Telephoto Hyperspectral Robotic

Array (MOTHRA), with 1140 telephoto lenses spread over 30 large fork mounts at

the Obstech observatory in Chile. The upgraded array will be equipped with

ultra narrow-band tilted interference filters, a technology pioneered by the

Dragonfly Spectral Line Mapper. Upon completion, MOTHRA will be the equivalent

of a 4.7m aperture f/0.07 refractor with an R=800 integral field spectrometer

and a 9 square degree field of view.

For more information

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.