Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Two-body relaxation I: small perturbations add up

We'll make use today of several techniques for simplifying

complicated calculations.

- dividing a problem into limiting cases

- the impulse approximation

We'll also revisit a calculation that you've probably

seen in other classes:

Stars often appear in groups,

sometimes nested within other, larger groups.

Astronomers have identified several different

varieties of stellar clusters.

- Open star clusters

-

Open clusters consist of several hundred to several thousand stars,

usually very young -- from less than one million to

several tens of millions of years old.

One often can find variations in the density

of stars from place to place in an open cluster.

Image of NGC 6705 courtesy of

Encyclopaedia Britannica

The picture below shows both an open cluster,

M35, on the right,

and a much more compact object on the left.

Image of open cluster M35 and globular cluster NGC 2158 courtesy of

Astronomy Picture of the Day,

Evan Tsai

and LATTE: Lulin-ASIAA Telescope

- Globular clusters

-

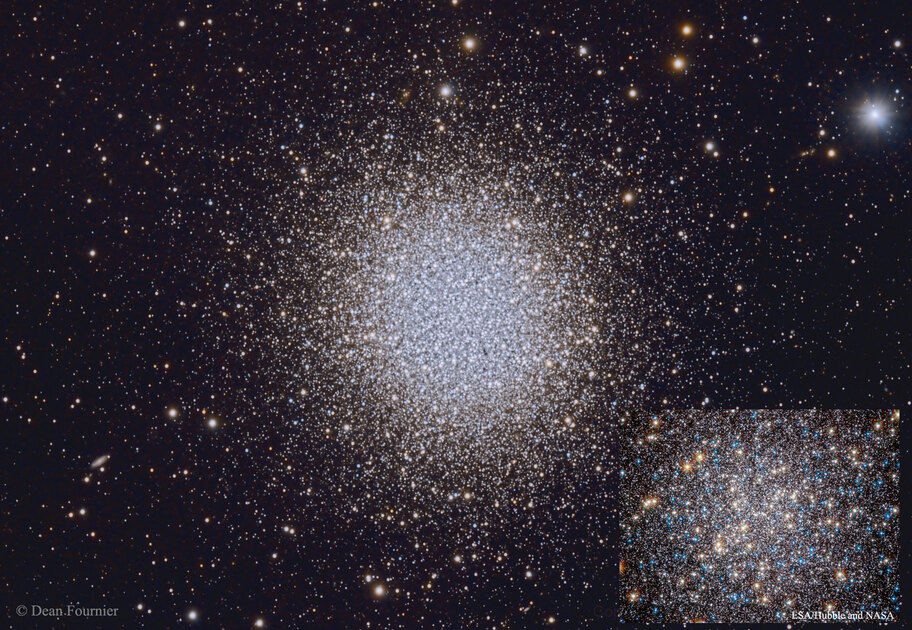

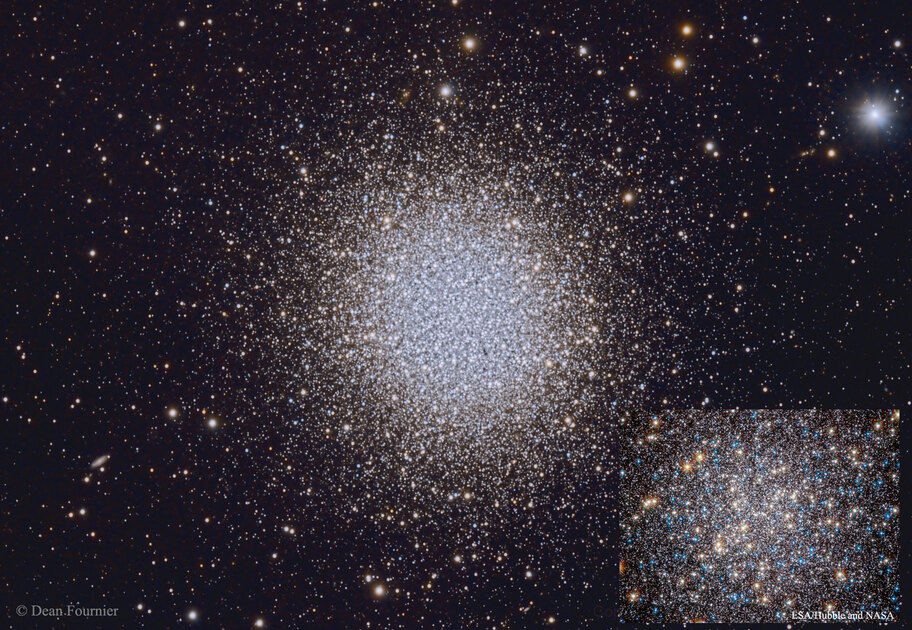

That compact object was a

globular cluster:

a dense collection of hundreds of thousands to millions

of stars,

all relatively low-mass and old (billions of years in age).

Globular clusters appear much less "lumpy" than open clusters,

and far more symmetric.

Image of M13 courtesy of

Astronomy Picture of the Day and

Dean Fournier;

Inset: ESA/Hubble & NASA

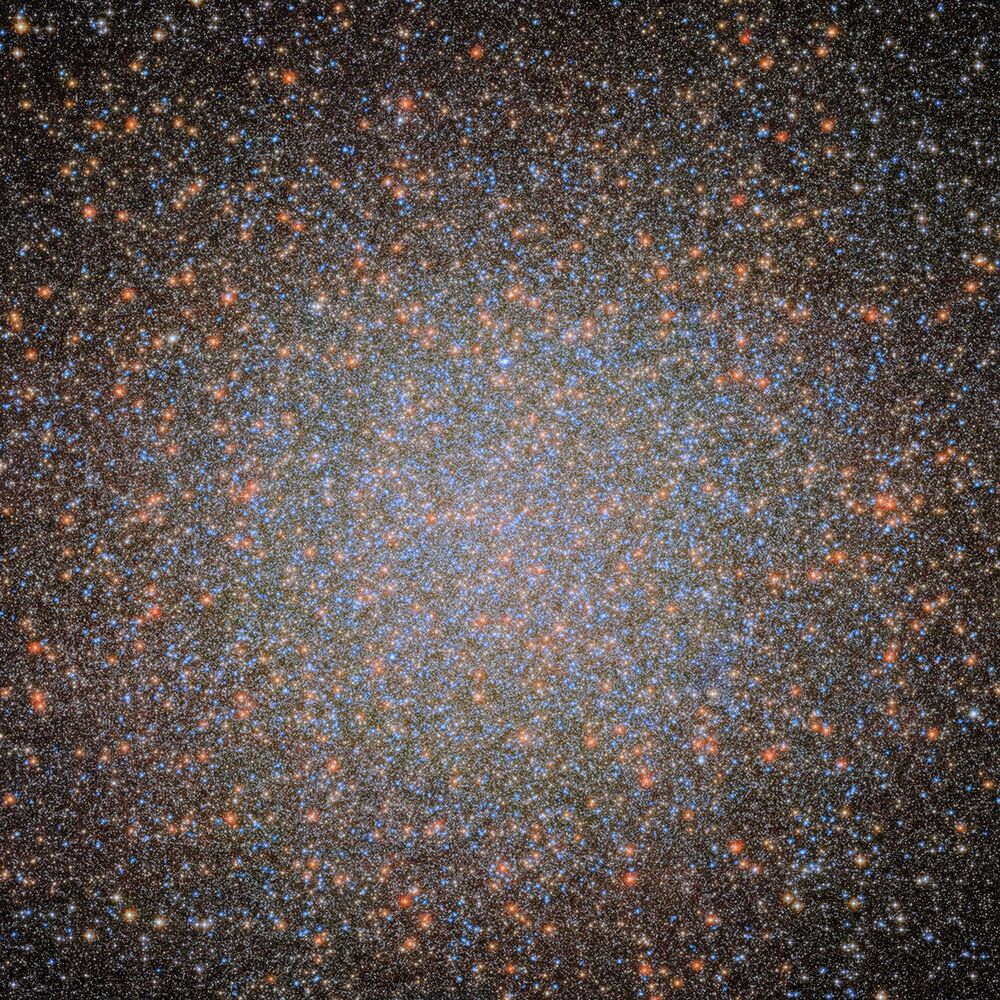

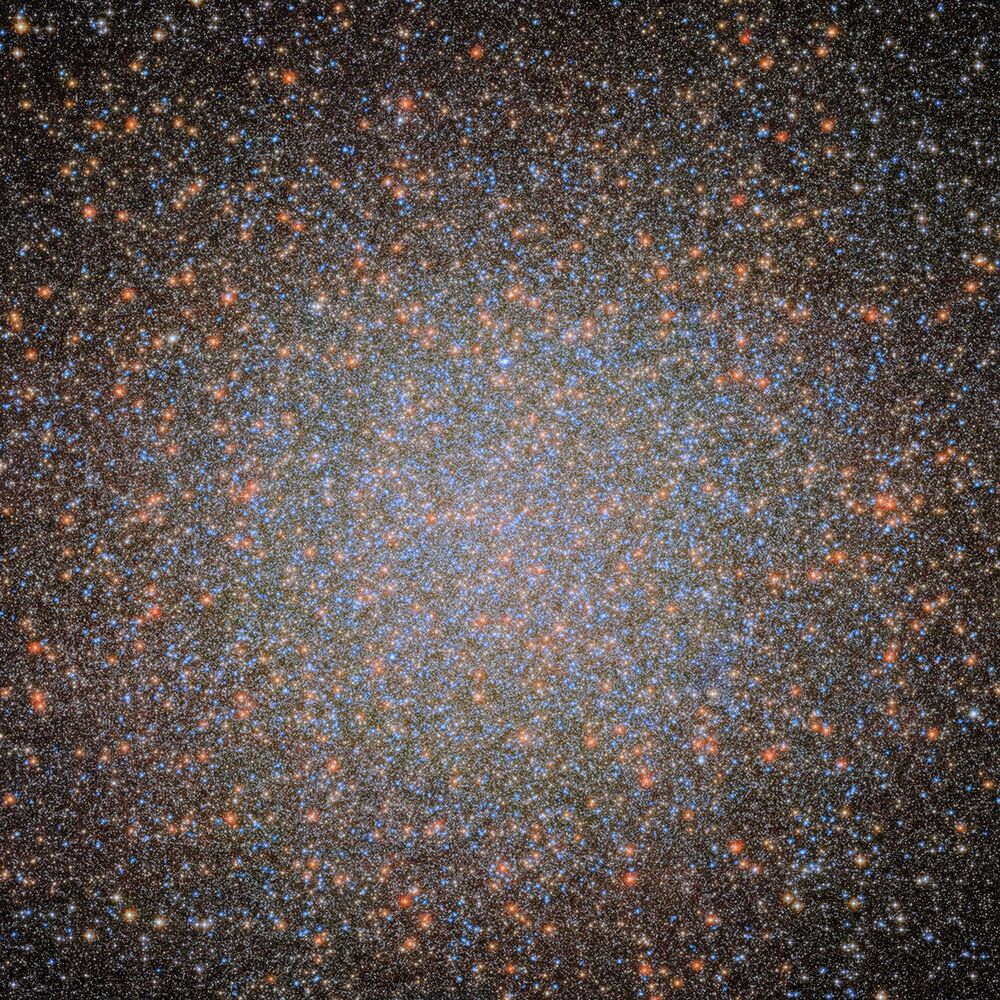

Image of M2 courtesy of

Astronomy Picture of the Day and

D. Williams, N. A. Sharp, AURA, NOAO, NSF.

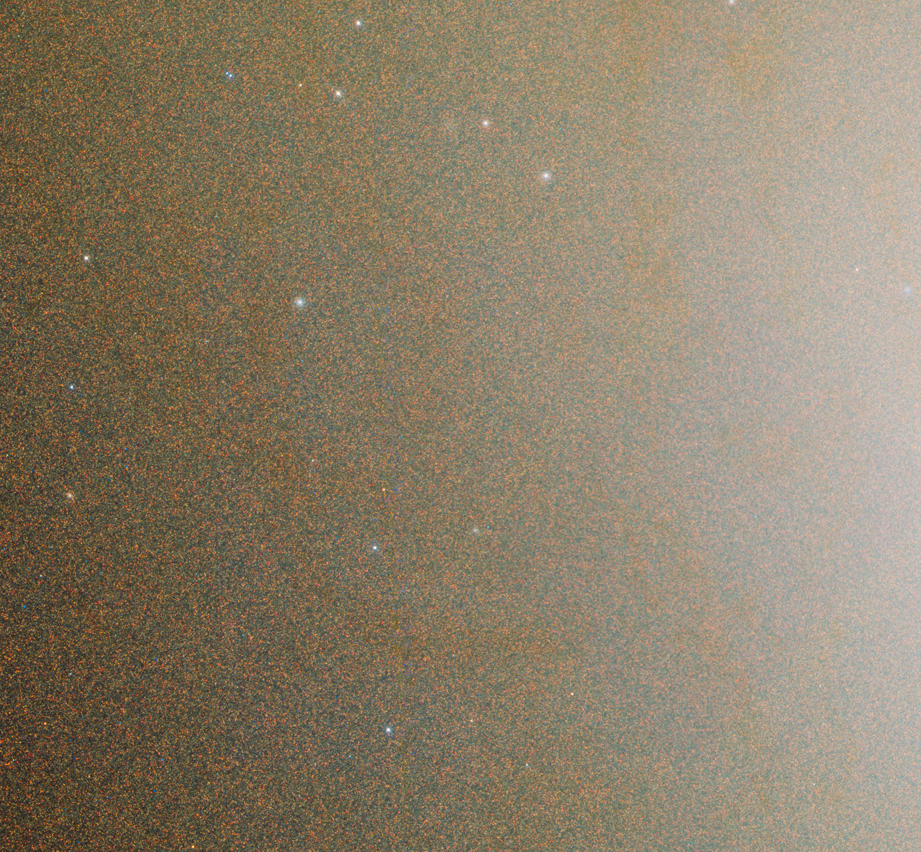

Image of omega Cen courtesy of

ESA/Hubble, NASA, Maximilian Häberle (MPIA)

-

- Galaxies

-

The dense bulge of the Andromeda Galaxy

is much, much larger than a globular cluster ...

but shows a similar uniform appearance

(at least from our very distant vantage point).

Image of M31 courtesy of

NASA, ESA, Benjamin Williams (UWashington), Julianne Dalcanton (UWashington)

Image of M31 (cropped section) courtesy of

NASA, ESA, Benjamin Williams (UWashington), Julianne Dalcanton (UWashington)

The goal today is to try to understand why relatively

young, low-density collections of stars show

"lumps",

but older, high-density clusters appear much smoother

and symmetric.

The answer will turn out to depend on the

nature and number of gravitational interactions

between the stars in the cluster.

We can break those interactions into three possibilities:

- direct physical collisions -- SMASH!

- close encounters creating strong gravitational perturbations

- very distant encounters with weak gravitational nudges

Which of these categories will turn out to be the most important?

The Sun has been revolving around the center of the Milky Way

Galaxy for a very long time.

It is surrounded by billions of other stars making similar

journeys.

What are the chances that, at some point(s) during its lifetime,

the Sun might collide -- really run into -- another star

in the disk?

Clearly, if that WERE to happen,

it could have catastrophic consequences for both stars

and for any planets around them.

Can we estimate the probability of such a collision?

First, note that since almost all the stars in the disk are moving

in roughly the same direction as they orbit the center of the Galaxy,

the relative speed of two stars is not their orbital speed

(around 200-250 km/s), but rather the velocity dispersion

in the disk.

That's a much smaller value, which could make a difference

in any calculations.

Let's adopt a typical value for the measured velocity dispersion

in the solar neighborhood:

- relative velocity v = 25 km/s

Next, if we ignore effects of gravitational forces between

the stars for the moment,

and compute the cross-section for interaction based on the physical

size of the stars -- as if they were tennis balls --

then we can make use of the same

mean free path

approach that we have used in the past.

Let's assume that both stars are identical to the Sun,

so we can adopt the solar radius to compute the cross-section.

The density of stars n locally is easy to estimate

now that Gaia exists:

simply visit

the Gaia archive

and count the number of stars within, say, 20 pc of the Sun.

I did so -- the result is shown below.

- solar radius r = 6.96 x 108 m

- density of stars n = 0.074 stars/pc3

Q: One pc = 3.08 x 1016 m. What is the density of

stars per cubic meter in the disk?

Q: Compute the mean free path of stars in the disk. Express

your result in meters.

My answers.

That sounds like a very large distance indeed.

How long would it take for such a collision to occur?

Well, we're assuming that the relative speed of stars

in the disk is about v = 25,000 m/s,

so ...

Q: What is the typical time between head-on collisions for a

star in the disk?

My answers.

Well, that's orders of magnitude longer than the Sun's lifetime

of about 5 billion years, and also orders of magnitude

longer than the age of the Universe.

It's safe to conclude that stars in the disk are unlikely

to suffer a head-on collision with another star in the disk

over any timescales of interest.

We've eliminated actual physical collisions as "improbable",

so we can move on to another case:

a close encounter, in which the two stars come close enough

to exert very strong gravitational forces on each other.

If we can quantify what we mean by "close encounter",

then perhaps we can also figure out how frequently this sort

of event might occur.

Let's use ENERGY as the quantity to help us define what "close encounter"

means.

Before the encounter, the two stars,

each with mass m and some random velocity of order v,

are very far away from each other.

At this time,

the total energy of the two-star system is

At the moment of closest approach,

on the other hand,

each star will have some new velocity v',

and the gravitational energy term will become important:

Let's define "close encounter"

to mean

the magnitude of the gravitational potential energy

becomes (at least) half of the total energy of the system.

In other words,

Q: Can you solve for the distance Rmin required for

a "close encounter"? Provide an answer in symbolic form.

My answer

Now, if we continue to assume that each star is identical in properties

to the Sun,

and has velocity equal to the velocity dispersion in the solar

neighborhood,

we can compute the value of this Rmin in real units.

Q: What is the value of Rmin in meters? In AU?

Q: How does it compare to the physical size of the Sun?

My answers.

Okay. The maximum distance for a "close encounter" is

considerably larger than it was for a "physical collision."

Does that mean that the Sun may have experienced one or more

of these strong perturbations during its lifetime?

Q: Compute the mean free path of the Sun for "close encounters."

Q: What is the time between such encounters?

My answers.

So far, we've ruled out direct collisions and "close encounters"

with other disk stars

as significant contributors to the trajectories of stars

in the Milky Way.

What's left?

Nothing but distant encounters, in which the gravitational forces

must be significantly weaker.

On the other hand, there will be many of them;

could there be enough for the accumulation of their minor

perturbations to amount to significant changes in a star's motion?

Let's find out.

In reality, there are small forces between the Sun and every other

star in the Galaxy, all the time, pulling in many different

directions.

It would be madness to try to deal with all those forces at once.

Therefore, we'll simplify things in the following manner:

- we'll consider the force due to a single star, as it passes

the Sun at a somewhat-closer-than-usual distance

- we'll employ the impulse approximation

to estimate the size of its gravitational influence

during this encounter

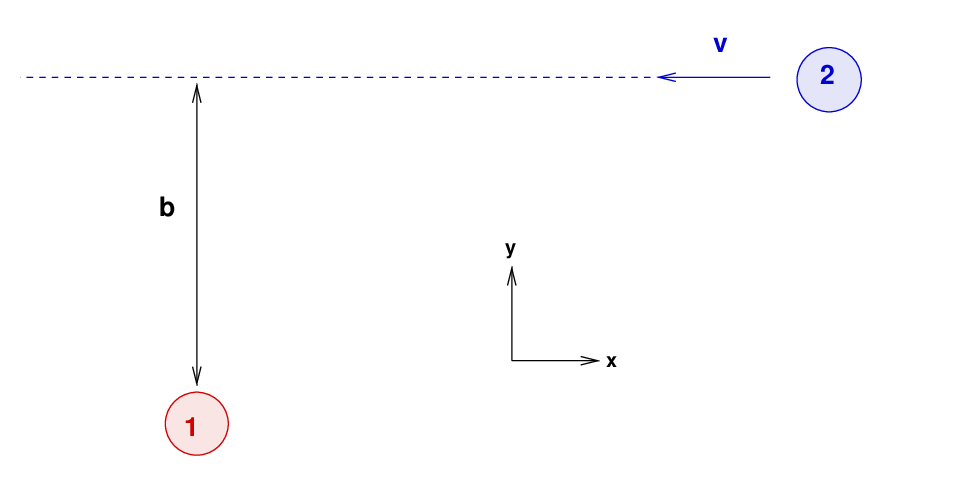

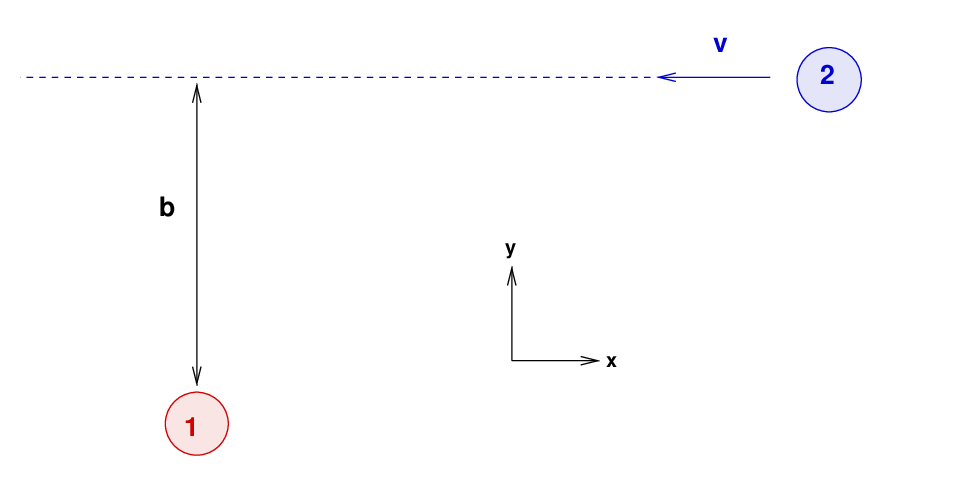

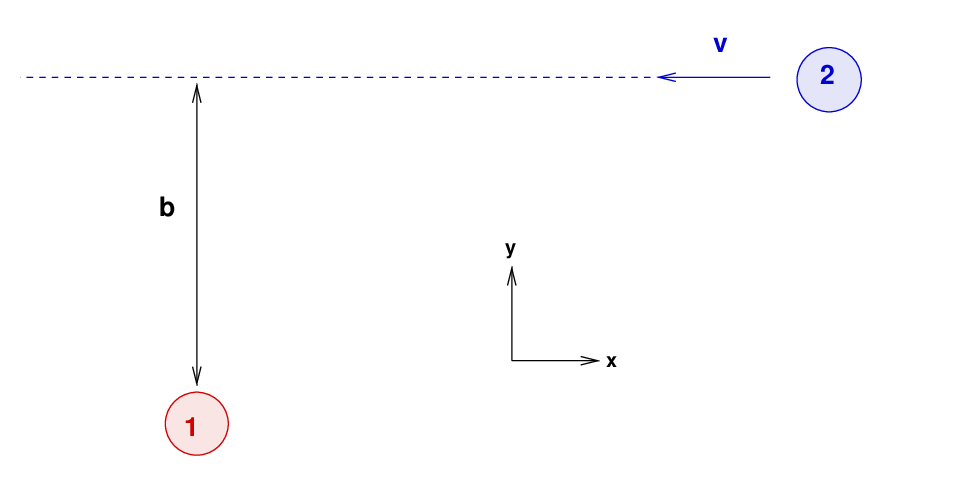

Here's a picture of the situation.

Star 2 moves past star 1 on a path which would -- if there were no

gravitational perturbations -- reach a minimum distance b.

The name for this hypothetical closest approach is impact parameter.

The goal is to determine the motion of star 1 which results

from the force between the two.

In real life, there would be a continuous gravitational force

pulling star 1 -- changing in size and in direction as

star 2 moves from right to left.

The

impulse approximation

states that one can find an approximate value for the

interaction in the following manner:

- assume that the force acts only during a brief period

- assume that the force has a constant size and direction during

that brief period

How shall we choose the period and the size of the force?

We don't have to be "perfect" -- we simply need to make

approximations which are good enough to yield a final

result within a factor of 2 or 3 of the actual, carefully-integrated

calculation.

Q: What would be a reasonable time for the duration of the force?

(Hint: use dimensional analysis to find some combination

of factors which produces a value with units of time)

Q: What would be a reasonable size for the force which acts during

this brief period?

(Hint: look at the picture)

Right. These are reasonable assumptions:

During this brief encounter, the force on star 1 is directed

in the positive y direction.

We can see from symmetry that any force in the x direction

must be zero.

As you may recall from your first-year physics courses,

the product of "force" and "time" is called

impulse,

and the impulse applied to an object is equal to the change in the

object's momentum.

That means

Q: Solve for the size of the change in the y-velocity of star 1.

Exactly.

Let's pause for a moment to examine our result.

We have an expression for the change in a star's velocity

as a result of some small gravitational force from

a distant, passing star.

Fine.

But how distant must the interloper be in order for our

approximations to be valid?

One way to address this question is to look at one of our

assumptions:

- assume that the force has a constant size and direction during

that brief period

If that's the case, then the actual distance between the two stars

ought to remain close to its value before the encounter;

in other words, the actual distance should remain very close

to b in our diagram.

We have just calculated that, as the star 2 passes,

star 1 will gain velocity in the positive y direction

and move toward its visitor.

How far will it travel during the encounter?

Well, distance travelled is just a combination of

velocity and time.

Now, in order for our assumption that the distance between

the two stars has a minimum value of b,

the displacement of star 1 towards its visitor --

PLUS the displacement of star 2 towards star 1, which will have

the same size --

must be very small compared to that initial separation.

Q: Estimate the minimum separation bmin which is

consistent with our assumptions. Assume that all stars have

the mass of the Sun, and move with the local velocity

dispersion.

m = 1.99 x 1030 kg

v = 25,000 m/s

My answer.

You should find that the minimum impact parameter

for weak interactions,

bmin,

is considerably larger than the maximum distance at

which strong encounters can take place.

That's good:

our methods are consistent with each other.

Stars passing at large distances will impart a small perturbation.

But how often will these little nudges occur?

- there must be more stars which pass at very large distances ....

- ... but the gravitational forces from those distant stars

will be much weaker

How often will the relatively nearby (but still distant) encounters

occur, and how will their relatively strong (but still weak)

contributions compare to those of the more distant visitors?

The first order of business is to figure out how frequently

encounters will occur, as a function of the

impact parameter b.

We'll use a slight variation on the good ol' mean free path

technique to quantify things.

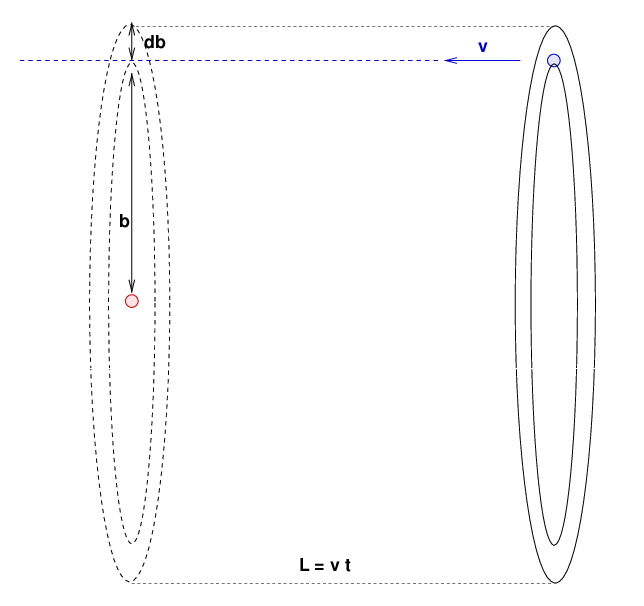

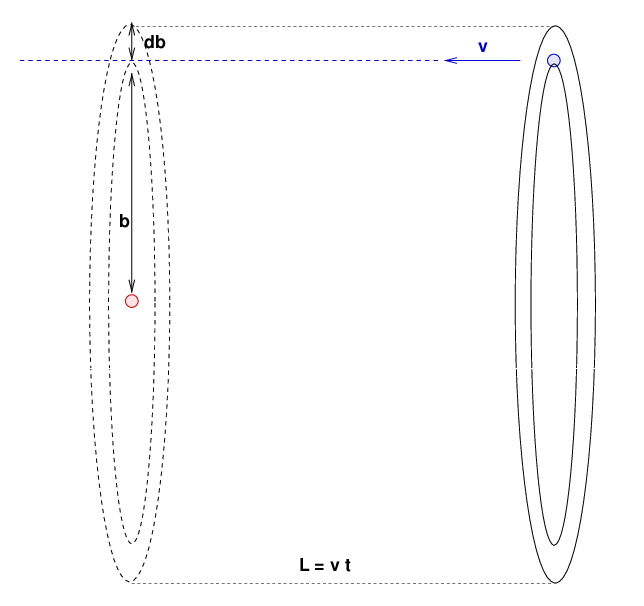

Consider stars which pass at impact parameters in the

range from b to b + db.

These can happen along a thin ring which has

inner radius b and outer radius b + db,

as shown in the diagram below.

Suppose we count all the encounters which occur in this

narrow range of impact parameters

over some period of time t.

The volume of space which is swept out

by this thin ring is a hollow cylindrical shell

which has volume

The number of encounters over the period t

within this narrow range of distance is

this volume multiplied by the density of stars in space, n.

At this point,

it ought to be clear that we will have to integrate over a wide

range of impact parameters b

in order to sum up all the perturbations due to weak

gravitational encounters.

However, there's a problem.

As the diagrams above make clear,

within each narrow range of impact parameter

lie stars at all locations around a circular ring.

Some will pull the target star up, some down, some to the left,

some to the right.

If we simply add up all the teeny-tiny displacements

in a proper vector sense,

we will end up with a net value of zero.

Whoops.

Or -- is that right?

It's time for a brief digression. Don't worry, it will all

make sense when we've finished.

Q: You are locked in a large room, 50 feet square. At the center

of the room is a zombie, sitting in a chair. You run to

a corner of the room and stand motionless.

The zombie stands up, unsteadily, and takes one step forward.

He loses his balance, spins around, and slowly takes another

step forward -- in a random direction. Again, he sways and

spins before taking a third step -- in another random direction.

Will the zombie reach you after taking a large number of steps?

Or will you survive, because the average position of the zombie

will be zero?

Do you recognize this problem?

It is often called a

random walk,

and crops up frequently in situations involving

many particles interacting with each other.

It turns out that, yes, the average value of the zombie's

displacement after N steps will be zero,

that doesn't mean that he will still be close to the chair.

His typical distance away from the chair will grow

with time,

but more slowly than one might expect.

The proper way to combine a set of randomly-oriented

steps is to look at the value of

the SQUARE of the displacement.

After a large number N of steps of size dx, the average value

of the zombie's distance from the chair will not be zero, but instead

√(N) dx.

Okay, now back to the stars and gravity.

What we need to do is to figure out the little change in

velocity

Δvy

due to one distant encounter at the impact parameter b,

and then add up the SQUARES of these

little changes over all distances.

Adding up the contributions of all the weak encounters

during some time period t

becomes an integral:

This may look scary,

but we can pull all the constant factors outside the

integral, which leaves a relatively easy problem:

Q: Can you perform the integral and write down the result?

Exactly.

At first glance,

this result looks as if it might lead to a crisis:

the if the upper limit of the integral --

the maximum impact parameter of passing stars --

happens to be infinite,

then the integral doesn't converge.

Oh, no!

Fear not.

The universe is not full of a uniform density of stars throughout

all of space.

For any particular gravitationally bound system --

a galaxy, or a globular cluster, or an open cluster of stars --

we simply need to estimate the minimum and maximum distances

for interacting stars.

Moreover, even if we don't know the EXACT size of the

system,

making a small, or even not-so-small, mistake when

choosing a value for the upper (or lower) limit

will probably not lead to a terrible result.

Because the function is logarithmic,

its output isn't very sensitive to small changes

in its input.

Q: Consider a star like the Sun, in the disk of the Milky Way Galaxy.

What is a reasonable value for bmin?

What is a reasonable value for bmax?

My answers.

Astronomers often use the symbol

Pick several different values for both limits

and calculate the value of

How large a difference does the exact value of the limit make?

We've worked our way through many steps in this derivation,

but we finally have a quantitative statement about the

accumulated effect of many small perturbations to the motion

of a star in the Milky Way.

In particular, we have an expression which describes

the overall sum in the quantity

|Δvy2|.

The question is -- when does this change become "significant"?

When does the motion of the star deviate enough from its original

trajectory that it becomes impossible or at least difficult to retrieve its

original velocity?

We will choose the following criterion:

when the accumulated changes have an amplitude which

is equal to the original trajectory's value of

v2.

With this choice,

we can replace the left-hand side of our integral

expression with the original velocity squared:

Q: Re-arrange this equation to solve for the time it takes

for the accumulation of weak gravitational perturbations

to change a star's velocity "significantly".

Very good.

Astronomers have a special name for this duration:

the relaxation time.

If a system of stars is allowed to interact with itself

for this period of time,

then the velocities of the stars will take on a

form known as a Maxwellian,

and any "lumps" or "voids" in the spatial distribution

will disappear into a more uniform arrangement.

Note that the value shown here may differ from values found

in other sources by factors of 2 or 4,

due to slightly different assumptions made during the

derivation.

Those factors aren't very important --

the goal here is to find an order-of-magnitude

estimate for the timescale over which

a self-gravitating system of many objects

will "relax."

Q: What is the relaxation time for stars in the disk of the Milky Way

Galaxy? Use the same values we've adopted earlier,

and choose your own limits to compute Λ.

- Looking for illustrations of random walk processes?

- What's the probability of two stars colliding directly?

There are many ways to approach this problem,

so considering several is a good idea.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.