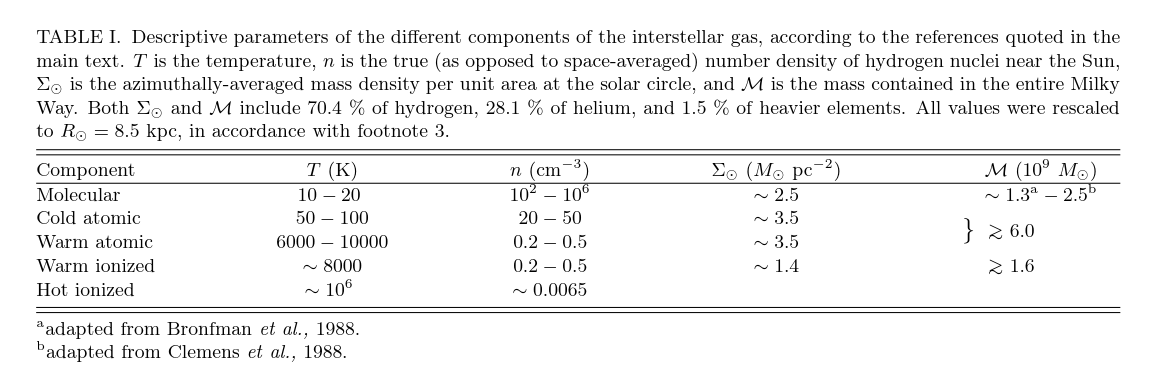

Table 1 taken from Ferriere, K. M., Reviews of Modern Physics, 73, 1031 (2001)

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

The topic today is how giant clouds of cold molecular hydrogen (H2) can contribute to the birth of new stars.

Table 1 taken from

Ferriere, K. M., Reviews of Modern Physics, 73, 1031 (2001)

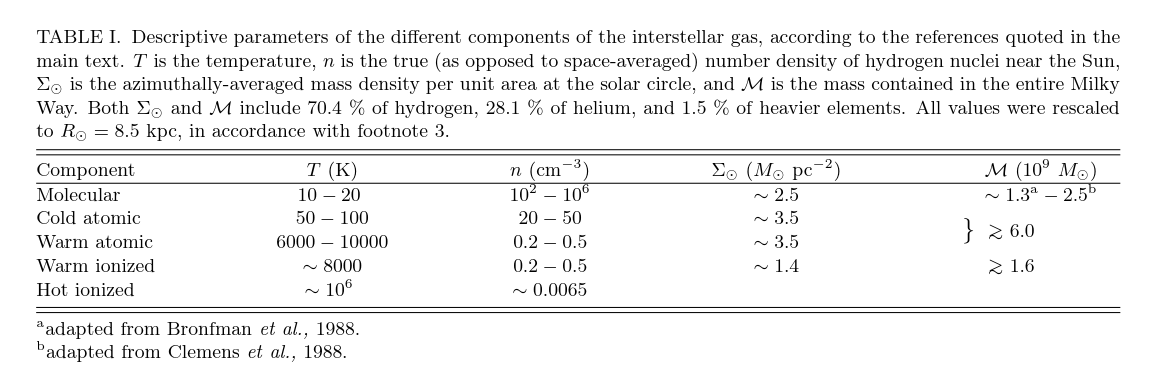

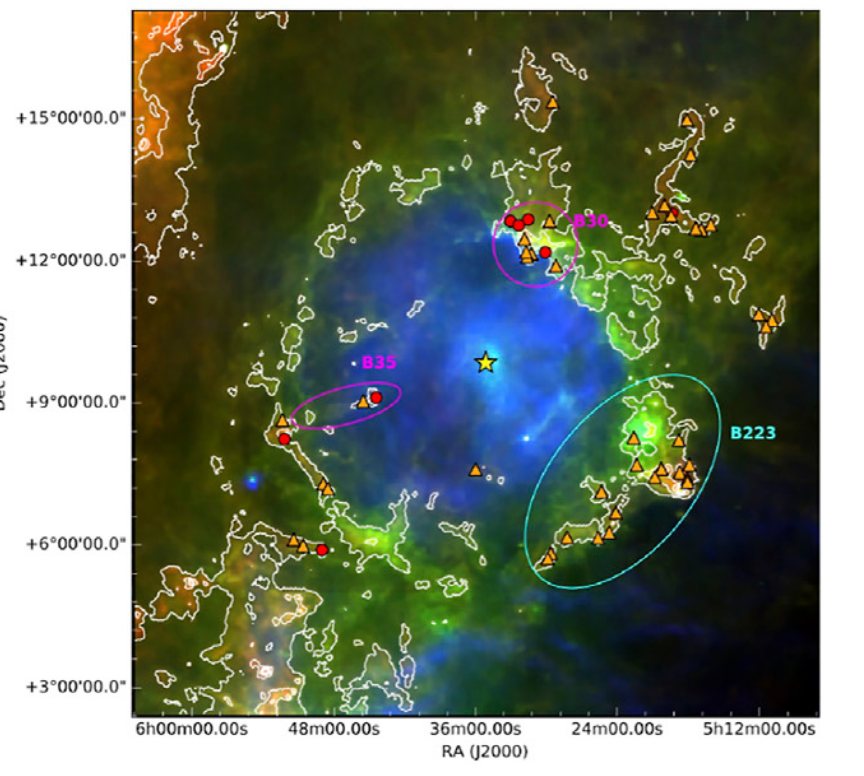

Astronomers have long noted the close connection between giant molecular clouds (GMCs) and regions of star formation. For example, consider the familiar constellation of Orion. On the left is an optical image, showing the bright stars marking the Hunter's shoulders and knees and belt, as well as the glowing gas of the Orion Nebula. On the right is a radio image of the same region of the sky, showing emission of CO -- which serves as a tracer for the presence of molecular hydrogen. Note that the Orion Nebula and its hot blue "Trapezium" stars appear within one of the brightest areas in the CO map.

Figure 1 taken from

Sahu, Liu, and Liu, Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences,

8, 672893 (2021)

The distance to the Orion Nebula and its associated molecular clouds

is roughly 450 pc.

Q: Using the angular size of "cloud A" in the right panel above,

calculate the linear size of that GMC. Is the term "Giant"

a good description?

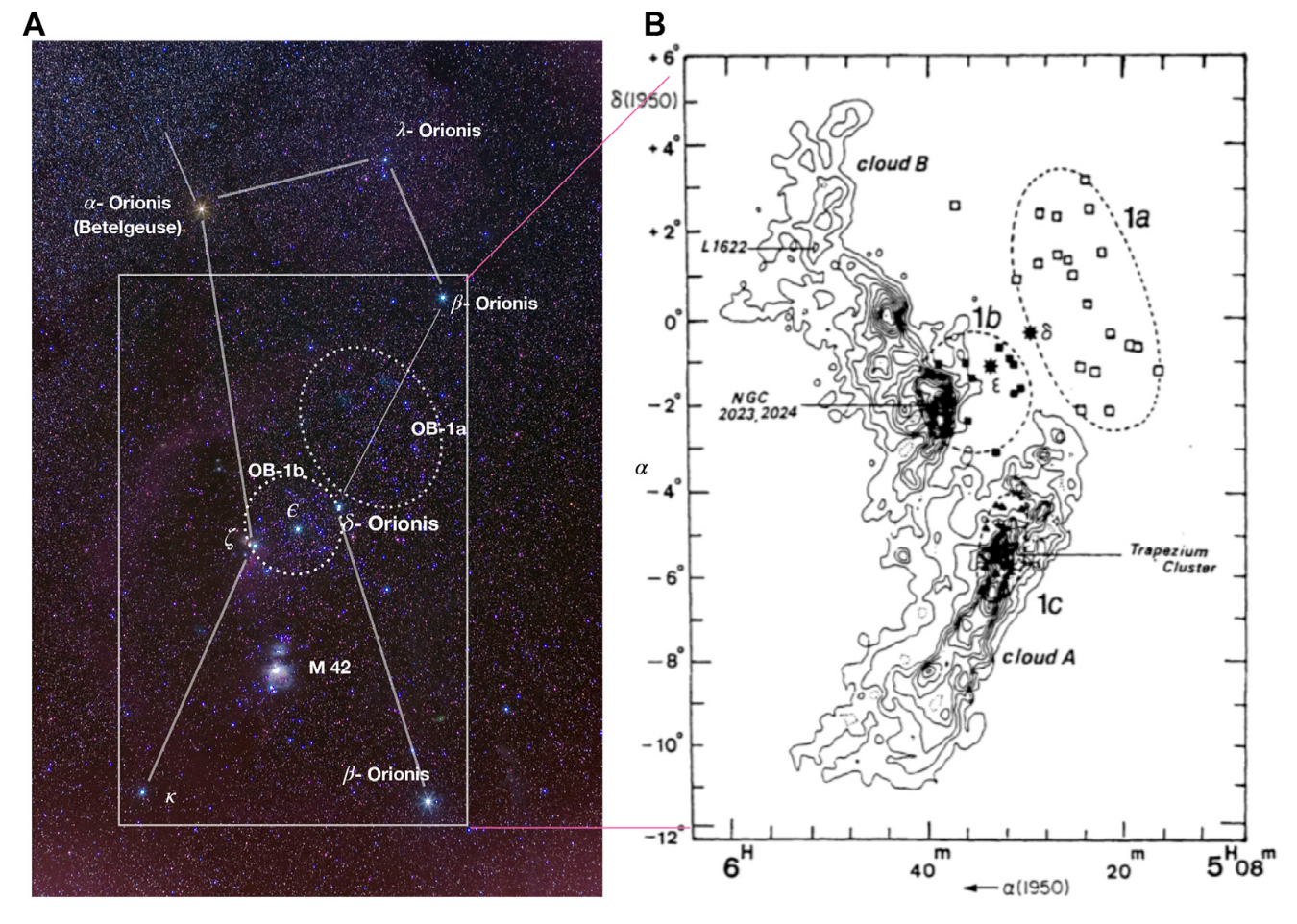

The left panel below shows infrared emission from dust -- another marker of molecular gas -- in the region around the Orion Nebula.

Figure 2 taken from

Sahu, Liu, and Liu, Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences,

8, 672893 (2021)

In addition to the bright, blue, hot, young stars we can see in the optical images, such as the members of the Trapezium Cluster inside the visible Orion Nebula, this region is full of younger stars, and proto-stars yet to be born, hiding inside shrouds of gas and dust. In the figure below, the yellow triangles and red circles mark the position of very young stars which have yet to "break out" of their molecular clouds.

Figure 6a taken from

Sahu, Liu, and Liu, Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences,

8, 672893 (2021)

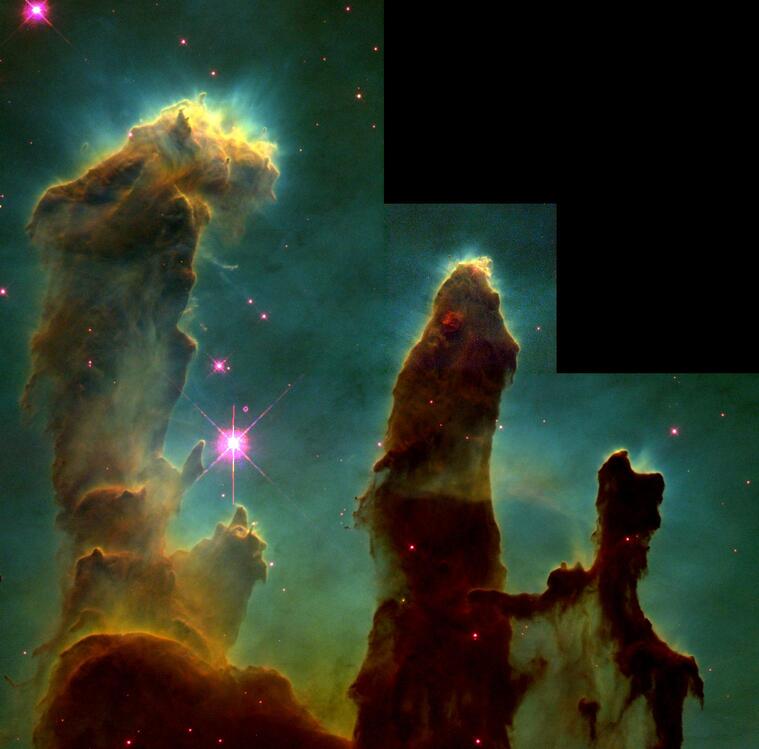

The famous "Pillars" image taken by HST shows a different molecular cloud; not in Orion, but the one known as Messier 16, or the "Eagle Nebula." Small portions of this molecular cloud have stretched out like "fingers" or pillars. Inside these pillars, small regions have started to collapse and form new stars. One can see several little nodules of gas and dust sticking out of the main "fingers;" each nodule contains a star at its end, most still hidden inside their dusty surroundings.

Image courtesy of

NASA, ESA, Hubble Space Telescope, J. Hester, P. Scowen (ASU)

So, clearly, some of the gas in molecular clouds does collapse on itself, growing denser and denser (and hotter and hotter) until gas particles are crushed so close together that they begin to fuse. At that point, we call the tiny ball of hot gas a star.

But why does a cloud of gas collapse? And why do some clouds collapse, but others do not?

Suppose a cloud of gas, with some particular average density, size, temperature, and composition, floats in the interstellar medium. Choose a cloud which is far from any stars or other massive objects, so that no external forces play any significant role in its behavior. If we watch over some extended period of time, what will happen?

It turns out that any of these three futures is possible -- depending on the properties of the cloud.

What are the important factors? Let's apply the virial theorem to find out. In one simple form, the virial theorem states that a system of particles interacting with each other via gravitational forces will remain in equilibrium as long as the following relationship is true:

Here,

Note that the kinetic energy must always be positive, and the gravitational potential energy is usually negative. If the two are equal, then the system remains as it is. If the kinetic energy is larger in size, the system is unbound and will expand; if the gravitational potential energy is larger in magnitude, then the system will collapse on itself, shrinking in size.

We can re-write the equation so that the two energies are on opposite sides,

and then simply ask "which side is larger in magnitude?" If left-hand side, expansion; if right-hand side, collapse. Only if the two sides are exactly the same will the system retain its shape and size over long periods of time.

Real clouds in the ISM are complex, and so trying to apply the virial theorem is a very tricky and complicated business. For example, if a cloud rotates, it has extra kinetic energy from that rotation; if the cloud contains lumps, then computing the GPE is no easy matter. For our discussion today, let's make a few (very) simplifying assumptions:

Under these circumstances, we can calculate the kinetic energy as simply due to the sum of random thermal motions of each atom or molecule,

and the gravitational potential energy as the self-energy of a uniform sphere:

Now, if we start with a very small cloud of gas -- say, a balloon-sized ball of radius 1 meter -- then gravitational potential energy is completely negligible. Even a very cold cloud of gas, at a temperature of just 2 or 3 Kelvin, will have enough kinetic energy for the atoms to fly off into space, never to return. But as the cloud grows larger and more massive, the gravitational potential energy starts to become important. Eventually, the gravitational forces will overwhelm the thermal motions of the particles.

Why can I write that so confidently? Look at what happens if we make one small modification to the equations. The total kinetic energy of the collection of N molecules

can be written in a slightly different manner. Let's introduce a variable μ = mean molecular weight which has represents the average mass of the molecules in the cloud in terms of hydrogen atoms. In other words,

The mass of a cloud of N molecules is therefore just the average mass of a molecule multiplied by the number of molecules.

Q: Can you write the number N in terms of mass M?

The result should be

Now, if we replace the N in the expression for kinetic energy with this combination of variables, we can re-write the virial theorem so that the mass M appears on both sides:

Now, how does each side of this equation depend on the mass of the cloud? The kinetic energy term (on the left) clearly increases linearly with the mass of the cloud: if one doubles the mass, one doubles the number of particles, and so doubles the KE. The GPE term (on the right) is a bit less obvious: the trouble is that as the mass M increases, so does the radius of the cloud R. We can solve this little puzzle by noting that for a spherical cloud of uniform density ρ, the mass is

Well, turning that inside-out yields

Aha! Now one can replace the R on the right-hand side with an expression containing mass M ... and so finally express how the GPE changes with the mass of the cloud.

Q: How does the KE increase as the mass M of the cloud increases? Q: How does the GPE increase as the mass M of the cloud increases? Q: Which term will win in the end as the M grows very large?

Yes, that's right: the kinetic energy grows linearly with M, but the gravitational potential energy grows faster, as M5/3. At some point, gravitational forces must dominate the dynamics of the cloud, and it will collapse.

Let's put this idea to the test. In order for a cloud to remain in equilibrium, it must satisfy

If the left-hand side (KE) is larger, then the cloud is gravitationally un-bound and will expand; if the right-hand side (GPE) is larger, then the cloud will collapse and, eventually, form stars.

Fine. We'll pick two representative clouds to find out what will happen to each in the future.

| cloud type | |

|

| density n (m-3) | |

|

| mean molecular weight μ | |

|

| temperature T (K) | |

|

| radius R (m) | |

|

| mass M (kg) | |

|

Q: For the atomic hydrogen cloud, which term is larger:

KE or GPE? How will this cloud evolve?

Q: For the molecular hydrogen cloud, which term is larger:

KE or GPE? How will this cloud evolve?

Okay, we have one way to determine the future of a cloud of gas: measure a bunch of its properties, compute both the total kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy of its component molecules, and compare their magnitudes.

But is there some more general way to predict the behavior of a cloud of gas? We've already seen that in VERY small clouds, the kinetic energy term is always more important, while in very large clouds, the gravitational term dominates. It's reasonable to conclude that there must be some intermediate size at which the two terms balance ... but is it possible to find some not-too-complicated expression for this critical size?

James Jeans was a very clever astronomer and thinker. In a paper published in 1902, Jeans described a way to determine the critical mass (or size) of a uniform cloud; in his honor, the result has been called the Jeans mass (or Jeans length).

His argument goes as follows. Start with the virial theorem for a spherical cloud of gas of uniform density. In equilibrium, the kinetic and gravitational terms must be equal.

Replace the radius R in the GPE term with

Now divide both sides by mass M and do a bit of algebra to simplify; the result is

Q: Solve this equation for M, so that it appears on the

left-hand side and all other symbols are on the right.

You should find

The quantity MJ is known as the Jeans mass. Clouds more massive than this threshold will collapse, and, in the long term, give rise to a number of stars.

In July of 2025, science news websites trumpeted big clickbait headlines:

The actual story was somewhat more prosaic -- but still exciting to astronomers.

Title of

Butterfield, Morgan, and Barnes, ApJ 988, 99 (2025)

In a location on the sky not far from the direction to the center of the Milky Way, where optical telescopes show a rich star field crossed by dust lanes ...

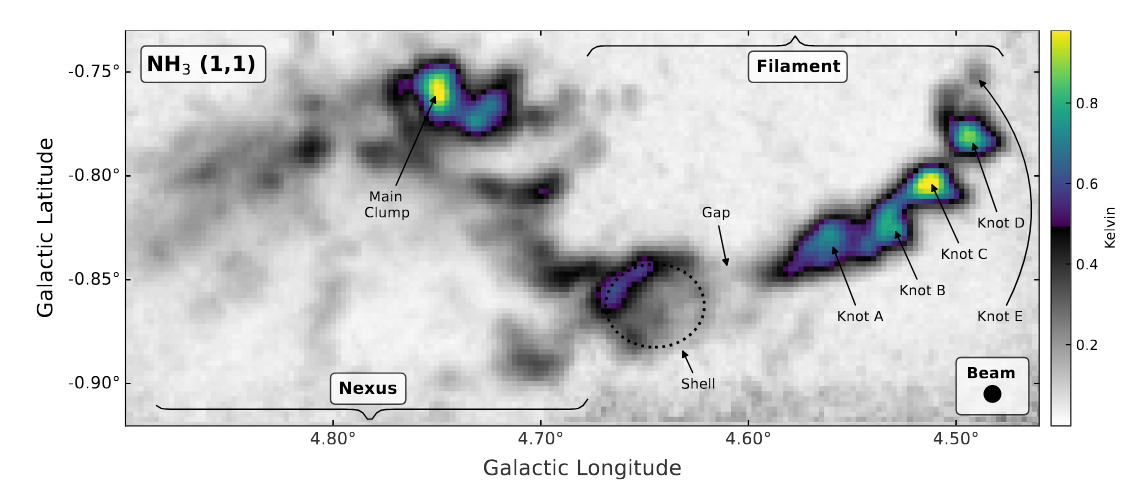

... radio astronomers noticed sources of radiation from a set of associated molecular clouds. The image below shows light emitted by of the (many) rotational transitions possible in ammonia molecules, at a frequency of 23.69 GHz. This map reveals the location of dense clumps, or cores, of gas within a larger molecular cloud complex.

Figure 2a from

Butterfield, Morgan, and Barnes, ApJ 988, 99 (2025)

Q: This cloud is located about 7000 pc away from the Sun, close

to the center of the Milky Way (which is about 8000 pc away

from the Sun).

Use the angular extent of this map to estimate the linear size

of the molecular cloud.

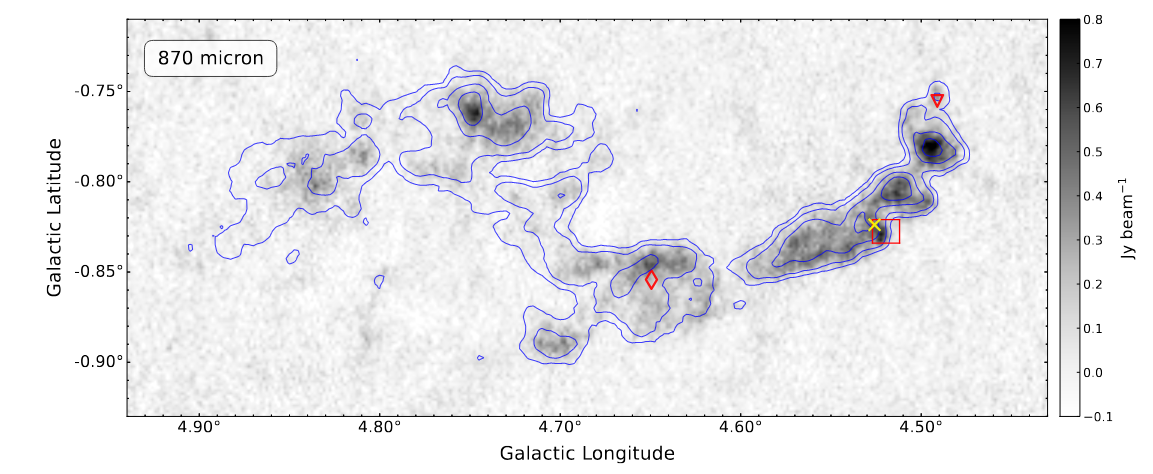

Another set of images, taken by a ground-based telescope at a wavelength of 870 microns, shows spots where dust, warmed by optical and near-infrared light emitted by nearby stars, re-radiates the energy in the far infrared. Note the correlation between the locations of radio (molecular gas) and far-IR (dust) emission: more evidence that dust is in integral component of molecular clouds.

Figure 8, showing thermal emission from dust, from

Butterfield, Morgan, and Barnes, ApJ 988, 99 (2025)

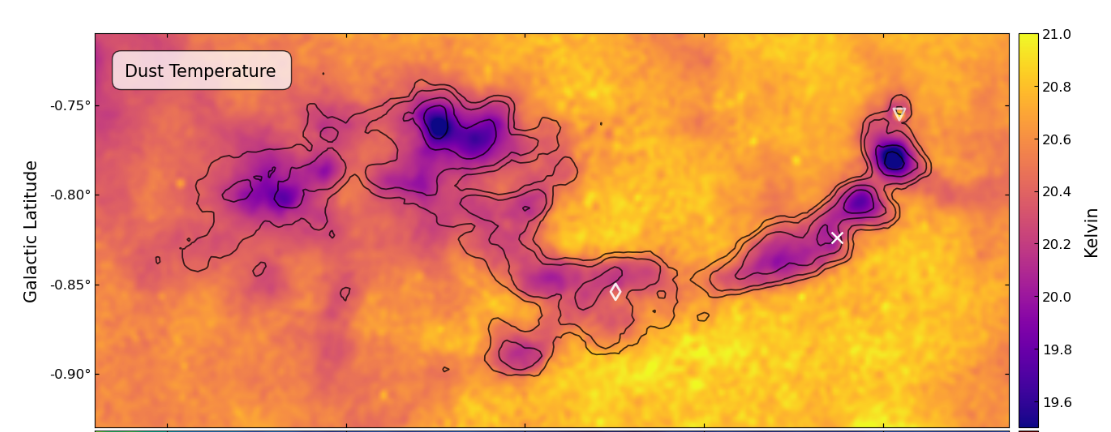

Strangely enough, the dust glows most brightly when it is warmest.

Figure 11, showing temperature of dust, from

Butterfield, Morgan, and Barnes, ApJ 988, 99 (2025)

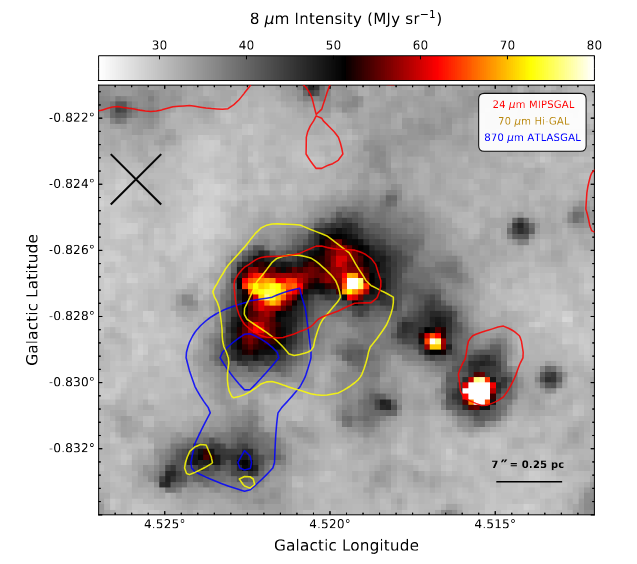

A closeup of the region around "Knot B" shows a combination of energy emitted at 25 microns (red) and 70 microns (yellow) in the mid-infrared, and at 870 microns (blue), all superimposed on a background greyscale image showing 8-micron continuum emission. The authors suggest that this particular set of dense clumps are the locations where new stars are forming right now. They speculate that the offset of the 870-micron emission (in blue) from the compact source observed at other wavelengths may indicate the presence of a jet, shooting outward from a protostellar object.

Figure 14 from

Butterfield, Morgan, and Barnes, ApJ 988, 99 (2025)

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.