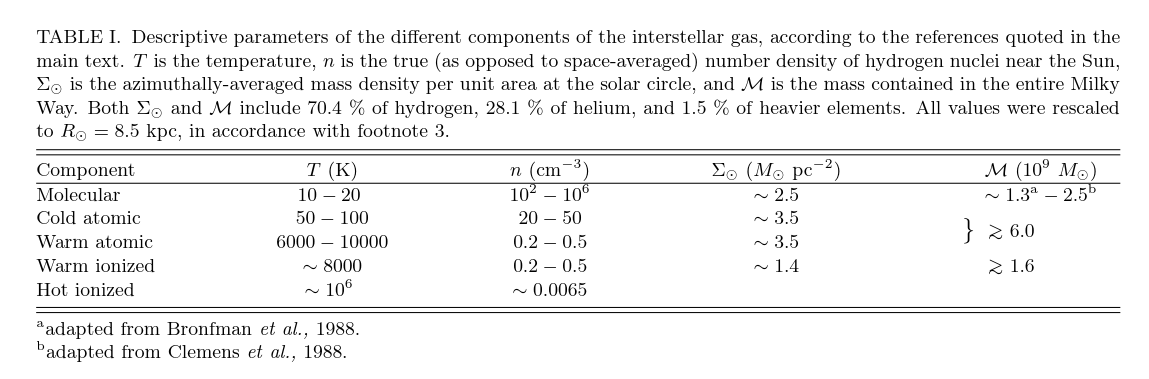

Table 1 taken from Ferriere, K. M., Reviews of Modern Physics, 73, 1031 (2001)

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Today, we look at an important component of the ISM: the dust which lies within molecular clouds.

Table 1 taken from

Ferriere, K. M., Reviews of Modern Physics, 73, 1031 (2001)

Before we look into any details of this very hot gas, let's use the table of properties above to get a rough idea for the TOTAL MASS of this component. How does it compare to the mass of the molecular phase, for example?

Oh, wait. There is no mass listed for the "hot ionized" phase. Rats.

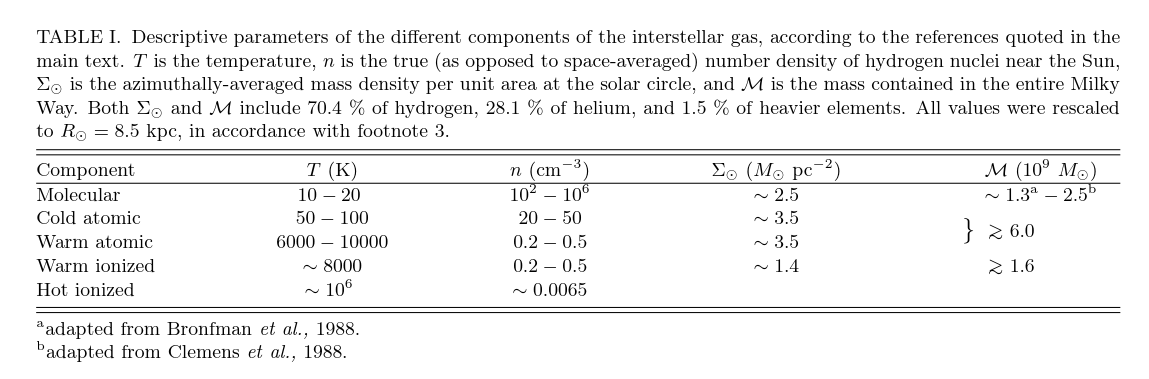

Well, we can get a rough idea by doing a quick calculation ourselves. Most of the gas in the Milky Way is confined to the disk. To a very rough approximation, this disk has the shape of a flattened cylinder, with dimensions

Q: What is the volume of this cylinder, in cubic kpc?

Q: What is the volume of this cylinder, in cubic cm?

Q: Assuming that the hot ionized phase completely fills this

cylinder (which it does not), how much mass would it contain?

Q: How does that compare to the measured masses of the other

phases of the ISM?

Now, this calculation will over-estimate the mass of the hot ionized gas, so it's safe to say that the MASS of the hot component is only a small fraction of all the interstellar medium in the Milky Way. Most of the atoms are in colder, denser forms.

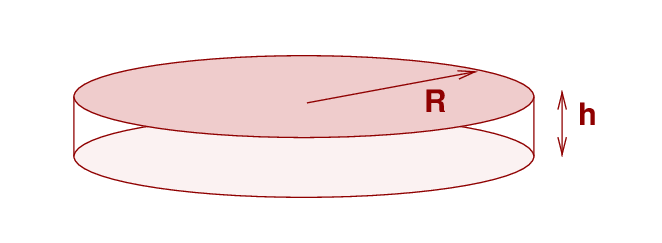

Before we can start examining this very hot gas, we need to understand the units which will be used to describe our measurements. Very hot gas emits, for the most part, X-rays. In the optical range, scientists typically mention the wavelength of light, or its frequency. The spectrum of a star in the optical will often have "wavelength measured in nm" on the horizontal axis, like this:

But astronomers have settled on a somewhat unusual unit to describe X-ray photons: keV = kilo-electron-Volts, a measure of energy.

1.609 x 10-19 Joules

1 keV = 1000 eV = 1000 eV * --------------------------

1 eV

keV are related to the wavelength of photons in the usual manner:

1240 eV * nm 1.240 keV * nm

wavelength (nm) = -------------- = ----------------

energy (eV) energy (keV)

The region of the electromagnetic spectrum labelled as "X-ray" has no official boundaries, but I tend to adopt this range of energies and wavelengths:

Energy (keV) 0.1 - 500

Wavelength (nm) 10 - 0.002

Wavelength (Angstrom) 100 - 0.02

This table might come in handy at some point.

| wavelength (nm) | energy (eV) | energy (keV) | wavelength (nm) | |

| 100 | 12.4 | 0.1 | 12.4 | |

| 10 | 124 | 0.5 | 2.5 | |

| 1 | 1240 | 1.0 | 1.24 | |

| 0.1 | 12,400 | 5 | 0.25 | |

| 0.01 | 124,000 | 10 | 0.124 | |

| 100 | 0.0124 | |||

| 500 | 0.0025 |

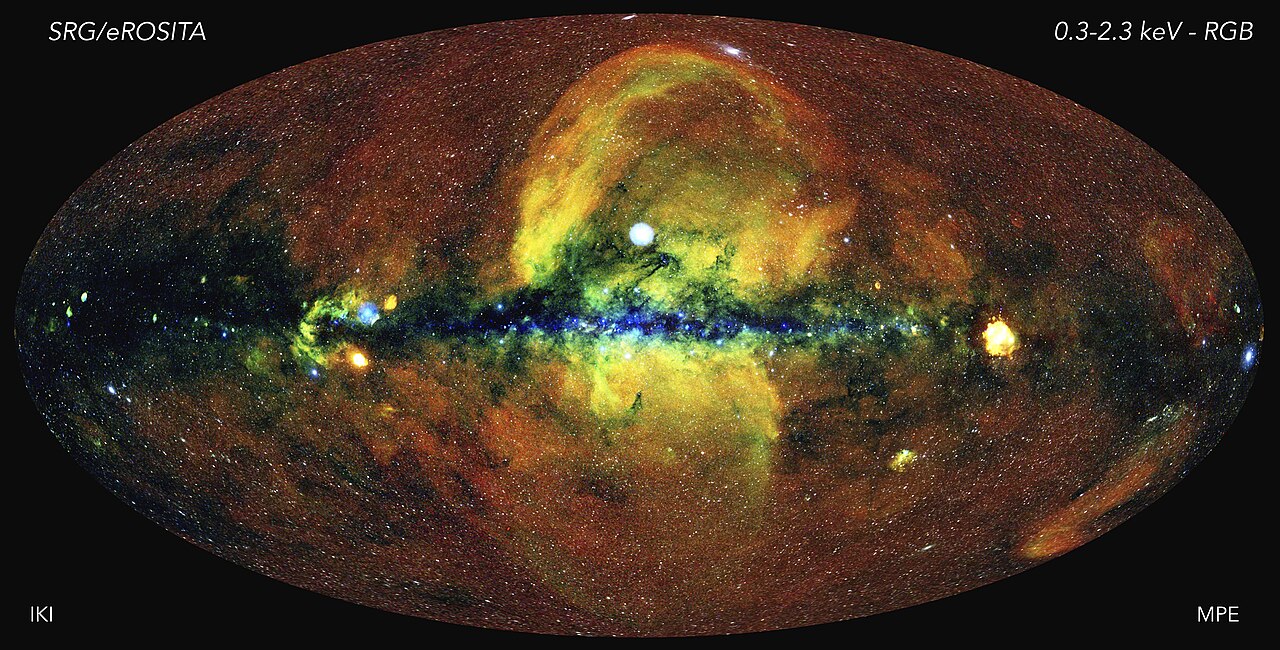

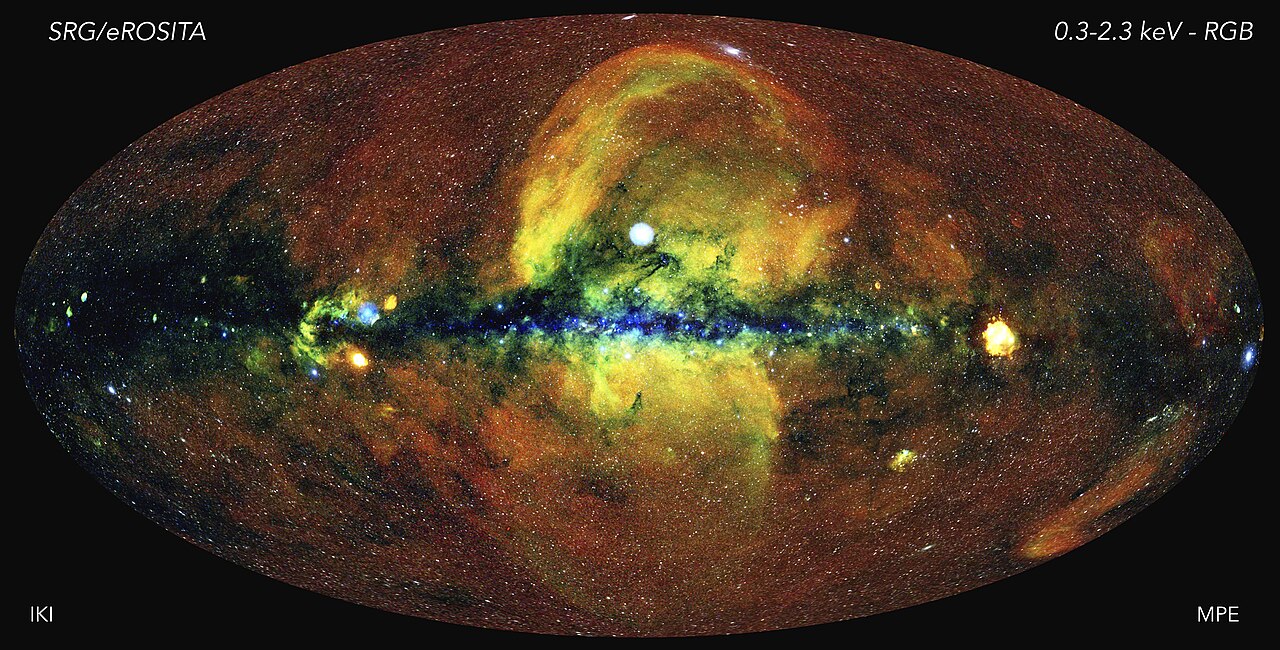

In order to see this very hot gas, we need to look in the X-ray portion of the spectrum; we'll discuss just how the gas emits X-rays a bit later. The eROSITA X-ray instrument aboard the Russian-German "Spectrum-Roentgen-Gamma" satellite has been observing the sky since December, 2019. It has covered the entire sky several times. The map below shows one of its datasets, plotted in galactic coordinates -- so that the plane of the Milky Way runs horizontally across the picture. In the map below, the colors correspond to the energies of the X-rays detected:

All-sky map courtesy of

Wikimedia.org and

Jeremy Sanders, Hermann Brunner and the eSASS team (MPE);

Eugene Churazov, Marat Gilfanov (on behalf of IKI)

Q: Where is most of the hot gas in the Milky Way?

Q: Do you see evidence for dust? What color are the pixels

near the dusty regions? What does that imply about

the ability of X-rays to travel through clouds of gas and dust?

Q: Are there any point-ish sources of X-rays?

Do you think they are inside the Milky Way, or outside it?

We have seen many instances in which objects emit blackbody radiation. Could this hot phase of the ISM do the same? Is blackbody emission responsible for the glowing wisps we see in the eROSITA map?

Well, just how hot would an object have to be in order to emit X-rays? The range of energies in the map is from 0.1 keV to 2.3 keV. As you may recall, the peak wavelength of a blackbody spectrum is

Q: What would be the temperature of a blackbody with peak at 0.1 keV? Q: What would be the temperature of a blackbody with peak at 2.3 keV?

The short answer is -- objects which emit X-rays tend to have temperatures around one million degrees or more.

But, actually, the hot phase of the interstellar medium does NOT emit blackbody radiation. As you may recall from physics classes, only solid, liquid, or very dense gas (like the gas in the Sun) emits via the blackbody mechanism. The density of the hot phase is much too low. So, how DOES it produce the X-ray photons that we see?

There are two main mechanisms:

Way back in the 1890s, when radioactivity and X rays were both new, exciting phenomena, some physicists noticed that if one shot a high-energy electron into a box of stuff, that it would come out the other end moving more slowly; moreover, the stuff would emit a bunch of X rays.

Because it seemed that there was some connection between the slowing down of the electron and the X-ray emission, physicists gave this phenomenon the name "braking radiation". Since most of those involved in this research were German, the word entered our vocabularies as brehmsstrahlung.

What's happening is the result of close encounters between the energetic electron and positively charged nuclei within the material. If the electron passes very close to a nucleus, the mutual electric force will accelerate the electron strongly; and an accelerating charge emits radiation, as we know from our E&M courses.

Because the electron might approach the nucleus to within any possible distance, it might end up emitting any wavelength of energy due to a single encounter. As it moves through the material, however, it will interact with numerous nuclei, and so the photons it emits will cover a wide range of energies and wavelengths; in other words, brehmsstrahlung produces a continuous spectrum.

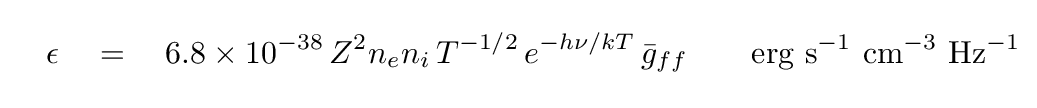

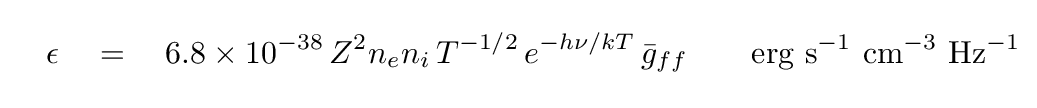

Now, in the 1890s, the source of the energetic electrons was radioactive decay. But out in space, the source of the energetic electrons is often a hot, ionized gas. In that case, the distribution of electron energies is dictated by the temperature of the gas, and so we call the process thermal brehmsstrahlung. In this common case, the emissivity of the gas -- a measure of how much energy it emits per second per unit volume per unit frequency -- can be written as

One important feature of brehmsstrahlung is that the emission depends on the SQUARE of the density of the gas; note that both the density of ions, and the density of electrons, appears in the equation. If a gas has a very low density, it won't emit much radiation by this process -- and so it might retain its thermal energy for a long time.

Another important feature of this emission can be gleaned from the form of the equation. Note the negative exponential term,

which will dominate the expression at high frequencies (or high energies), when

At these high frequencies (or high energies), the amount of energy radiated by the gas decreases rapidly. Sometimes, this critical point is called the cutoff frequency or cutoff energy.

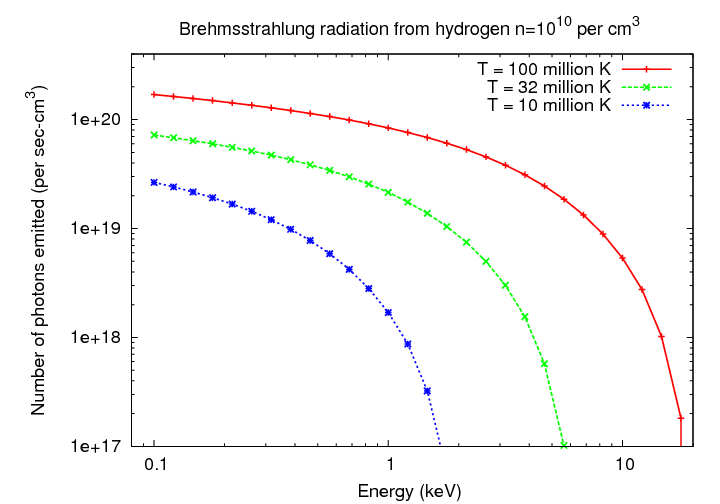

Q: What is the cutoff energy for hot gas of each of these

temperatures? Express your result in keV.

a) T = 1 million K

b) T = 10 million K

c) T = 32 million K

d) T = 100 million K

Compare your results to the theoretical brehmsstrahlung spectra below.

You are familiar with line emission from atoms, right? Atoms have quantized energy levels, and an atom in an excited state can drop to a lower-energy state by emitting a photon. In the case of hydrogen, for example, transition from state n=3 to n=2 results in a Balmer-alpha photon.

Q: Is it possible for a hydrogen atom to emit an X-ray photon?

No, hydrogen can't emit X-ray photons: the maximum potential energy difference, between the n=infinity and n=1 states, is just (0.0 - (-13.6)) = 13.6 eV.

However, other atoms have more protons in their nuclei, which create a stronger electric potential and the possibility of emission lines with higher energy. If an atom with atomic number Z (meaning Z protons in its nucleus) is stripped of all but a single electron, then its energy levels look very much like those of hydrogen -- but with an extra factor:

Q: What is the energy of a ground state, n=1, in this atom? Q: What is the energy of the n=2 state in this atom? Q: What is the energy emitted when this atom jumps from n=2 to n=1?My answers

Aha! Now, this sort of transition produces X rays! Please do remember the energy of that photon emitted by Fe XXVI ...

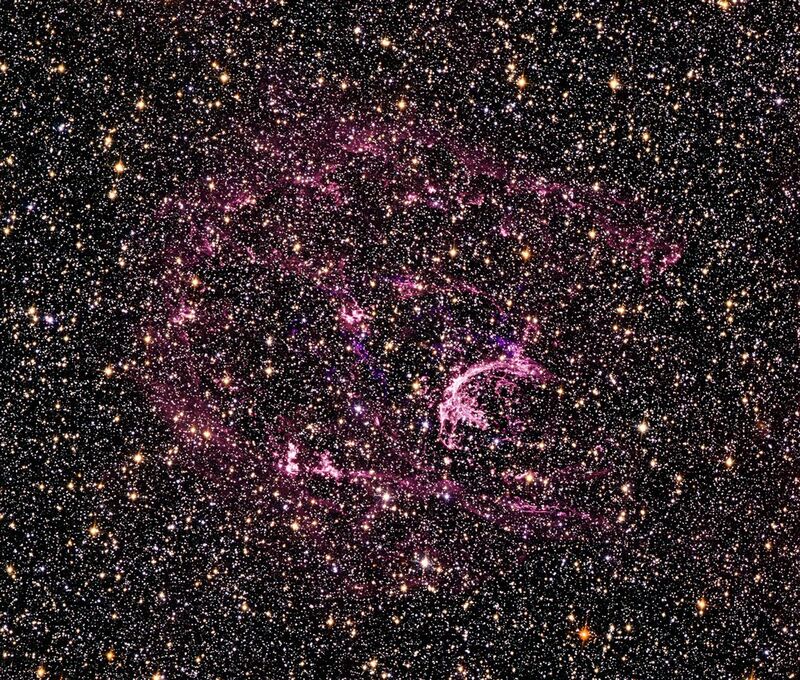

As an example of emission from the very hot, ionized phase of the ISM, consider the supernova remnant known as N132D. This was originally a big, hot star, perhaps 15 times as massive as our Sun. After fusing all the fuel near its center in just a few hundred thousand years, the star's core imploded, and the resulting release of energy blew it entirely to bits. Humans looking up at the sky around 3,000 years ago may have noticed a new star in this location for a month or two.

All we can see now in optical light are a few wisps of gas, originally part of the star's outer envelope, as they expand into space.

Image of SNR N132D taken by HST

courtesy of

NASA, ESA, and the Hubble SM4 ERO Team

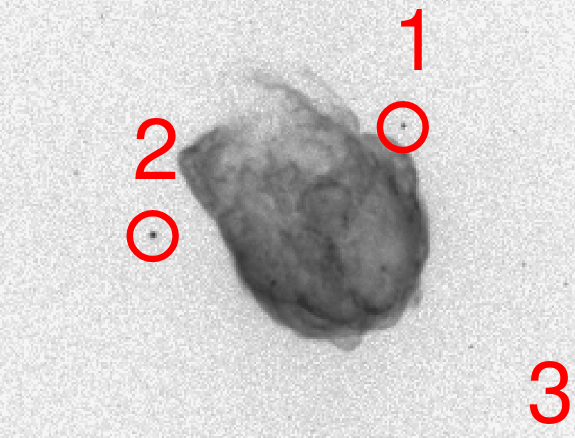

X-ray telescopes, on the other hand, detect a cloud of very hot gas.

Chandra X-ray image of SNR N132D from

Long et al., https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.12157 (2025)

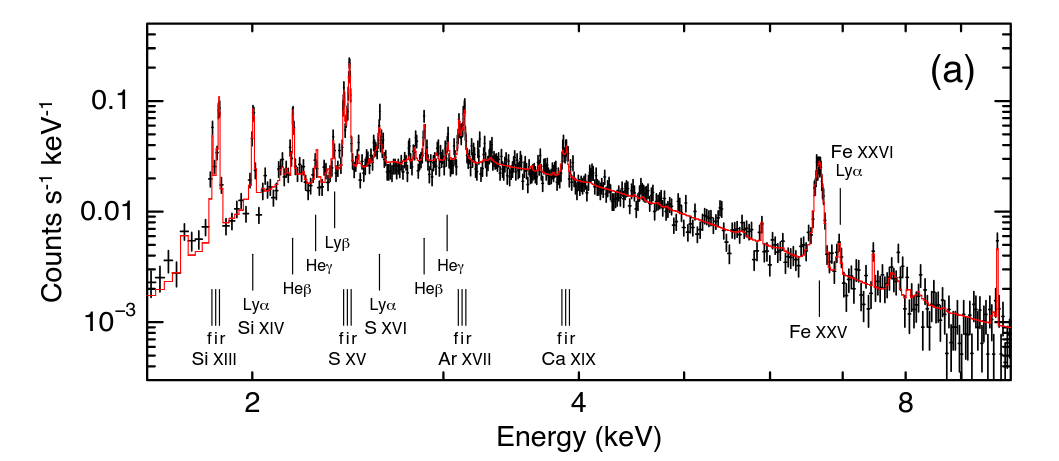

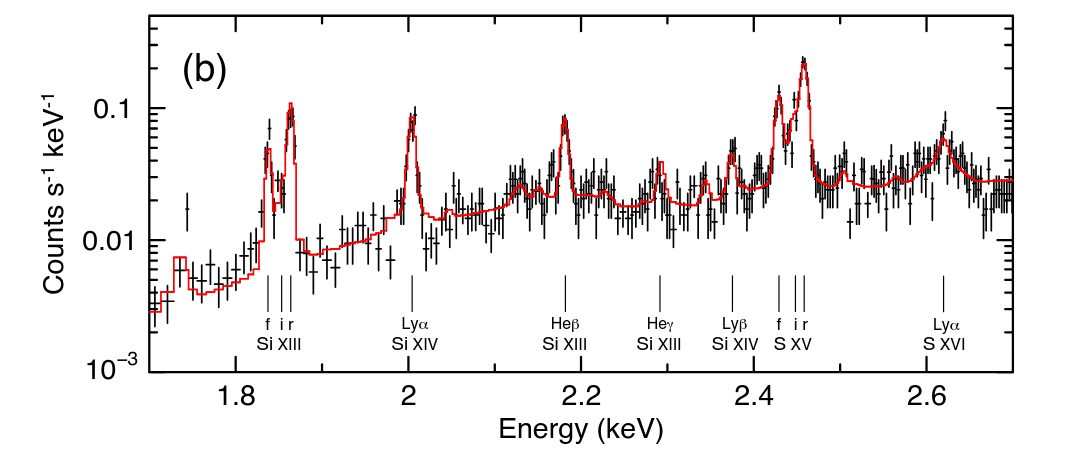

The XRISM satellite acquired an spectrum of the X-ray radiation emitted by this gas.

Figure 2a taken from

XRISM Collaboration et al., PASJ 76, 1186 (2024)

Q: Do you see evidence for a continuous spectrum produced by

brehmsstrahlung?

Q: Do you see evidence for line emission?

Yes, this is a good example: it shows both a continuous spectrum and line features. The continuum appears to decline at low energies due to absorption by the ISM between us and the supernova remnant; it would otherwise run nearly horizontally off the graph to the left, rising just a bit to lower energies.

Q: What is the energy of the line labelled "Fe XXVI Lyα"?

This closeup of the spectrum shows a wealth of lines due to various ions of silicon and sulfur.

Figure 2b taken from

XRISM Collaboration et al., PASJ 76, 1186 (2024)

Most of the material in interstellar space is cold -- just 5 or 10 or 20 degrees above absolute zero. Gas and dust which happens to be close to a star may be excited to temperatures of 10,000 degrees or so, but that's still far below the values seen in the hot, ionized medium. What can heat gas to temperatures of millions of degrees?

One answer:

SHOCKS!

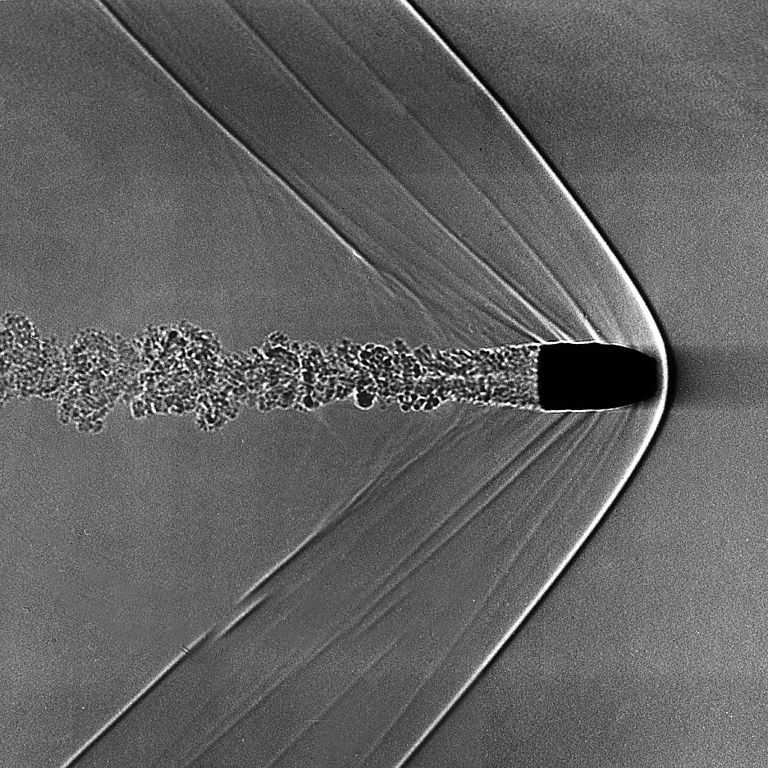

Image of bullet's shock wave courtesy of

Prof. Andrew Davidhazy and Wikipedia

A shock occurs when one object moves through a medium faster than the speed of sound in that medium. That means that the projectile pushes through the medium faster than the medium can move out of the way. The result is an interesting, but complicated, set of physical processes at the interface between the two. From our point of view -- a very very very simplified one -- we can consider the bulk motion of material before the collision (bulk kinetic energy) turning into disordered motion of atoms after the collision (thermal energy). Again, the real situation is more complicated.

In general, the material running into a shock with some initial speed vi and low initial density comes out of the shock with a much lower final speed vf, but a higher final density and final temperature.

Under certain rather common conditions, for a "strong shock" in which the incoming speed of the gas is much larger than the sound speed of the gas, the final speed is just 1/4 of the initial speed.

Q: A hydrogen atom approaches a strong shock with an

initial speed vi and leaves

with final speed vf = (1/4) vi.

How much of its initial kinetic energy is lost?

The lost kinetic energy can do a number of things. It can dissociate molecules, ionize atoms, excite atoms and ions that remain, and turn into thermal motions of the particles. If the initial speed is high enough, the results can create radiation in the X-ray regime.

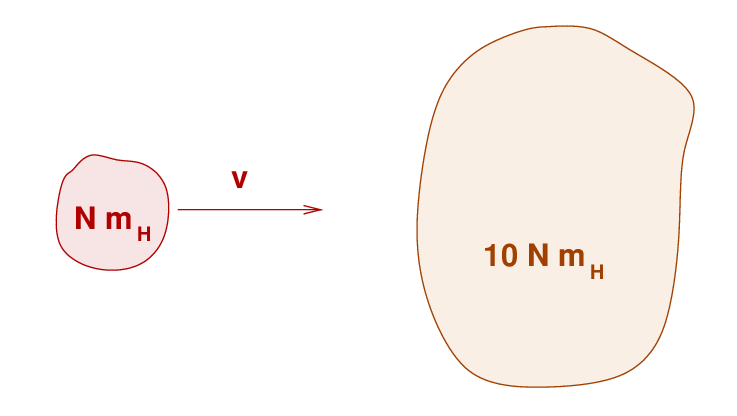

Let's do an order-of-magnitude calculation to see what sort of velocities are required to reach interesting results. We'll make a number of simplifications:

Q: Write an equation for the total energy of the system before

the collision (it should all be KE).

Q: Write an equation for the total energy of the system after

the collision (KE and thermal energy).

Now, can you solve for the final temperature of the gas after this collision?

Q: Write an equation for the temperature of all the gas

after the collision.

You should find

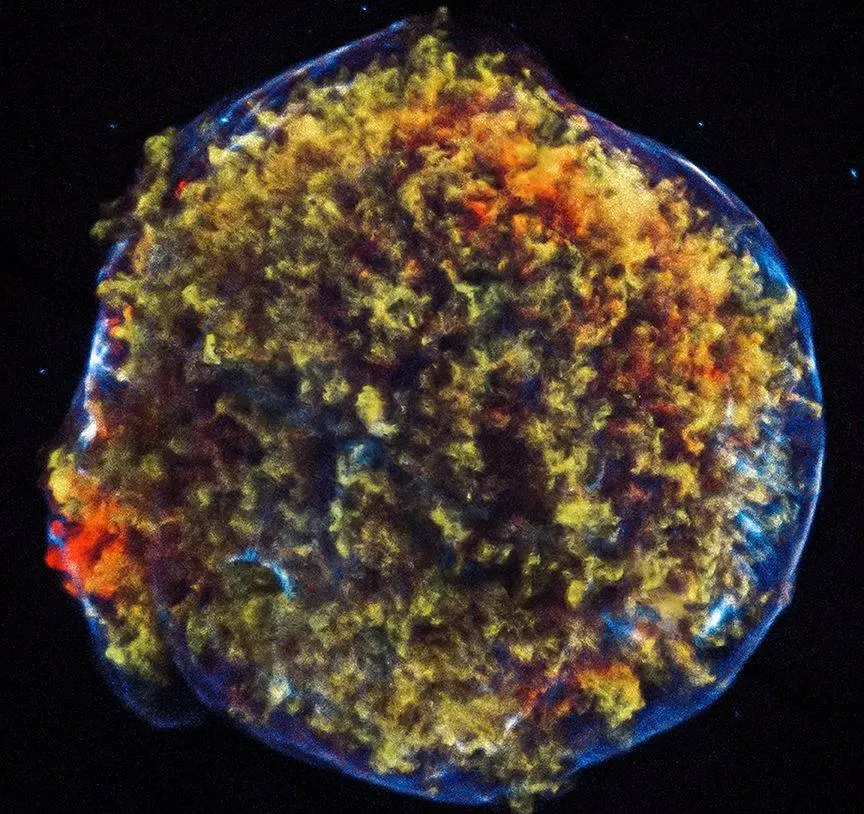

The real question is -- what are the velocities that could be involved in collisions like this? There are many different possibilities, of course, spanning a very wide range of velocities. Let's pick one of the most violent situations: a supernova explosion, like the one seen in 1572 which created Tycho's supernova remnant.

Chandra X-ray image of Tycho's SNR courtesy of

NASA/CXC/SAO

We have measured blobs of gas ejected from supernova explosions to have velocites of many thousands of kilometers per second.

Q: If the clump of gas has an initial velocity of v = 5,000 km/s,

what will the final temperature of the gas be?

The shocked gas will emit X-rays and other high-energy radiation. You can see some clear examples of shocks created by explosions or similar events in the eROSITA all-sky map.

All-sky map courtesy of

Wikimedia.org and

Jeremy Sanders, Hermann Brunner and the eSASS team (MPE);

Eugene Churazov, Marat Gilfanov (on behalf of IKI)

Very hot shocked gas will gradually radiate away its thermal energy. However, because its density is so low, and the rate at which it emits energy depends on density SQUARED,

the gas may lose its energy very slowly. Over the course of tens of thousands and even millions of years, shocked material will expand and expand and expand, becoming more and more wispy and thin.

Image of Crab Nebula courtesy of

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Tea Temim (Princeton University)

and

Astronomy Picture of the Day.

Image of Cas A courtesy of

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Danny Milisavljevic (Purdue University), Ilse De Looze (UGhent), Tea Temim (Princeton University)

Image of Veil Nebula courtesy of

Mikael Svalgaard and

Astronomy Picture of the Day

Eventually, the hot gas spreads out to fill large regions of space with a somewhat uniform "background".

Q: Look again at the all-sky X-ray map. Do you see evidence for

hot gas pervading the interstellar medium in the Milky Way?

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.