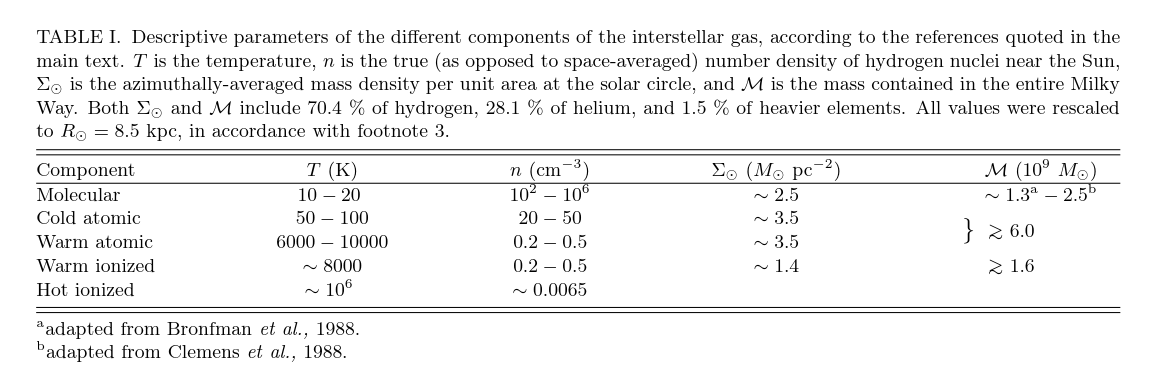

Table 1 taken from Ferriere, K. M., Reviews of Modern Physics, 73, 1031 (2001)

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

The topic today is the fate of clouds of gas which are close to hot, young stars. The result, as we shall see, are HII regions. They appear as "warm ionized" in the table below.

Table 1 taken from

Ferriere, K. M., Reviews of Modern Physics, 73, 1031 (2001)

If you've seen pictures of big, bright, reddish clouds of gas in space, then you should have a pretty good idea of what an HII region looks like. Note the hot, blue stars in the middle of the Orion Nebula.

Image of M42 courtesy of

Stefan Seip

and

Astronomy Picture of the Day

The Horsehead is one of the few DARK clouds to have a name. It sits in front of an HII region, and the dust within blocks the light from behind. These objects are part of the Orion Molecular Cloud, so neighbors of the Orion Nebula.

Image of Horsehead Nebula courtesy of

Daniel Stern

and

Astronomy Picture of the Day

This wonderful picture shows a sense of scale: the large Lagoon (on the right) and smaller Trifid (on the left) Nebulae are silhouetted against the central regions of the Milky Way. Note the difference in color between the bright red of the HII regions and the dull yellow of the innumerable cool stars around them.

Image of Lagoon and Trifid Nebulae in the midst of the Milky Way courtesy of

Jose Rodrigues

and

Astronomy Picture of the Day

The pictures show that HII regions are beautiful -- no doubt about that. But what is not so clear is their size: are these glowing portions of the clouds as large as our Solar System? Or are they bigger -- perhaps a parsec or two in radius? Could they be even larger -- almost as large as the molecular clouds from which they were born?

The goal for today is to figure out a typical size for these celebrities of the skies.

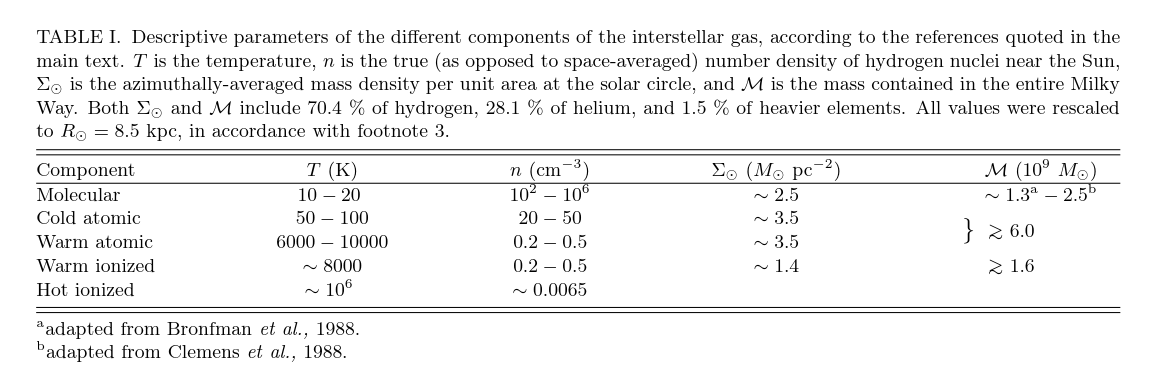

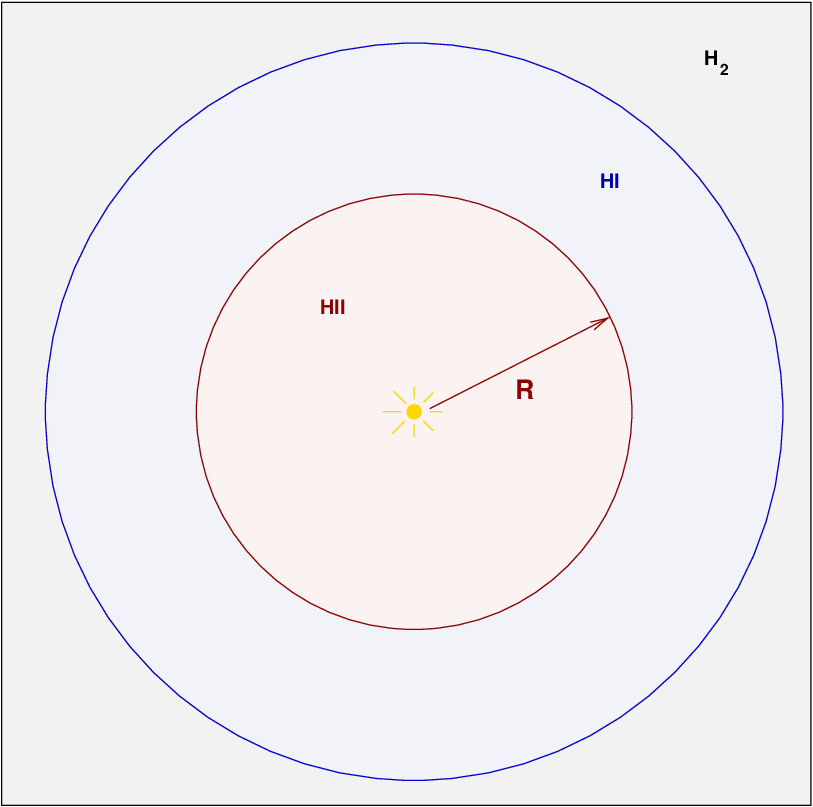

Suppose a giant molecular cloud DOES give birth to a star (in real life, clouds usually produce clusters of new stars very close to each other, but we'll simplify things). The star will shower the nearby gas with photons, heating it up, breaking up molecules, and perhaps ionizing some atoms. We might imagine that after some time has passed, the region around the star looks something like this:

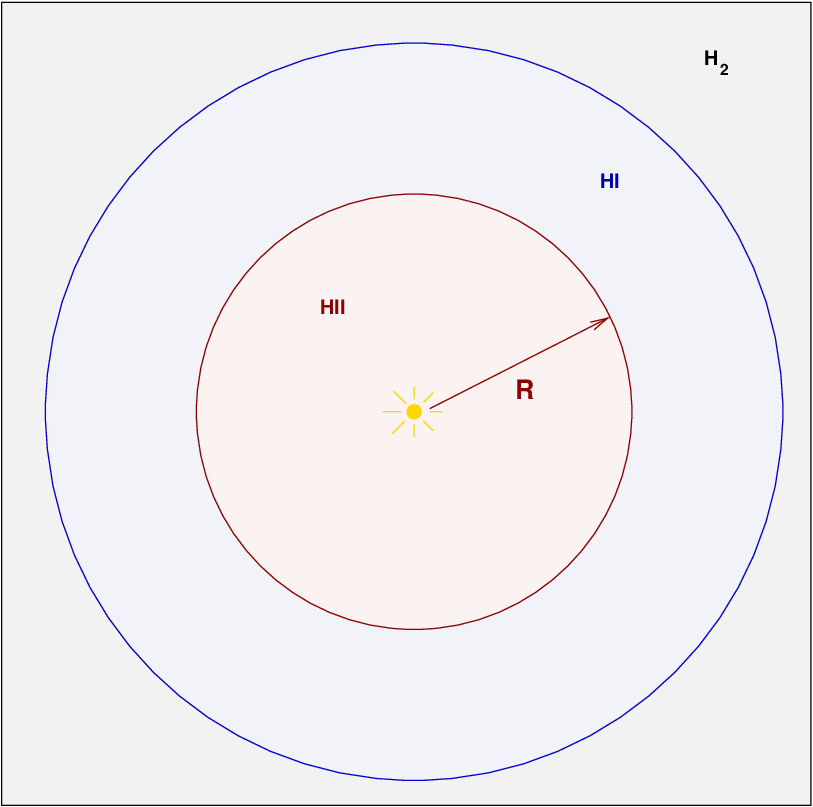

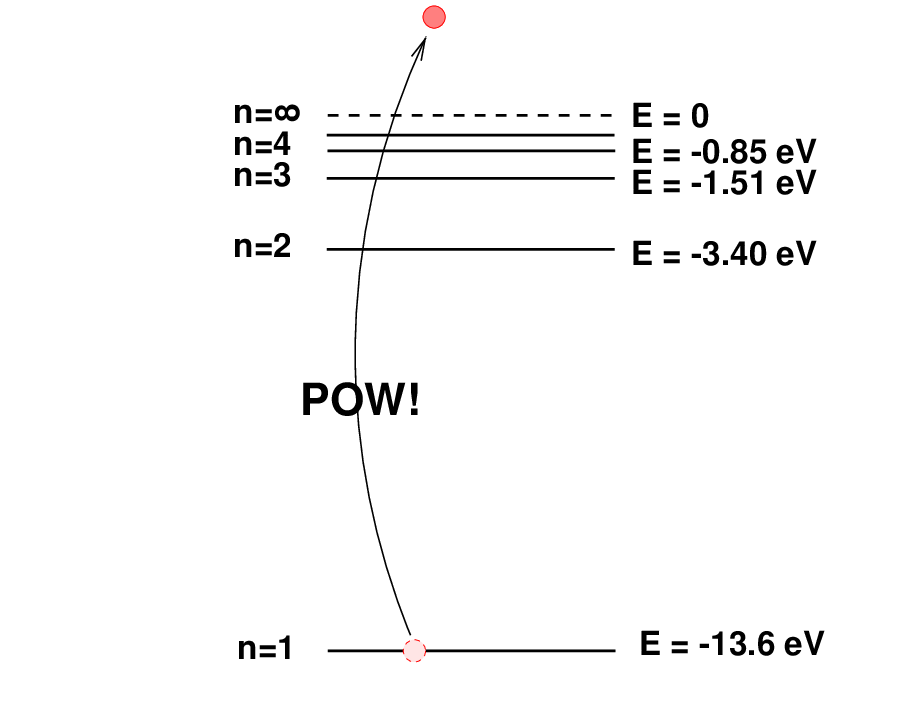

What exactly causes this region of ionized hydrogen around a star to emit a strong, reddish glow, so prominent in photographs? Consider an atom of neutral hydrogen. Quantum mechanics shows that it has a series of energy levels which follow a simple pattern of energy; I've only drawn the first four in the diagram below.

Most atoms will be in the lowest energy state, n = 1, also known as the ground state. If a photon with an energy of greater than 13.6 eV impinges on the atom,

Q: What is the wavelength of a photon with 13.6 eV of energy?

then the atom may absorb the photon, jumping into an energy state which ejects its electron. In other words, absorbing a photon with at least this amount of energy will ionize the atom.

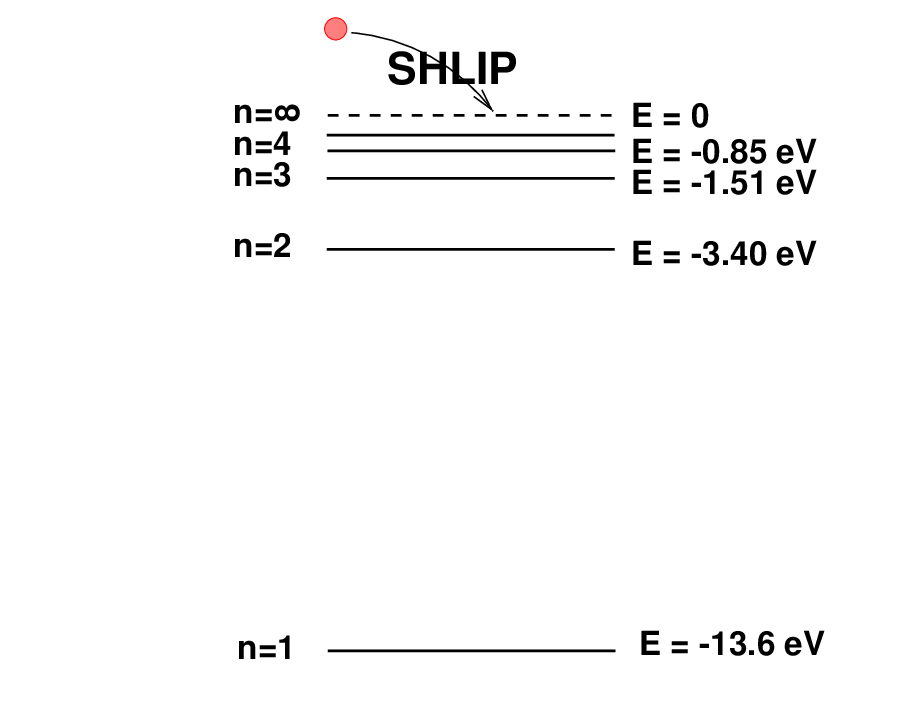

So, the gas near the star will become ionized. After some time, however, random motions in the cloud may cause a free electron to pass close to the proton; in some cases, the proton will recombine with the electron to create an atom of neutral hydrogen again.

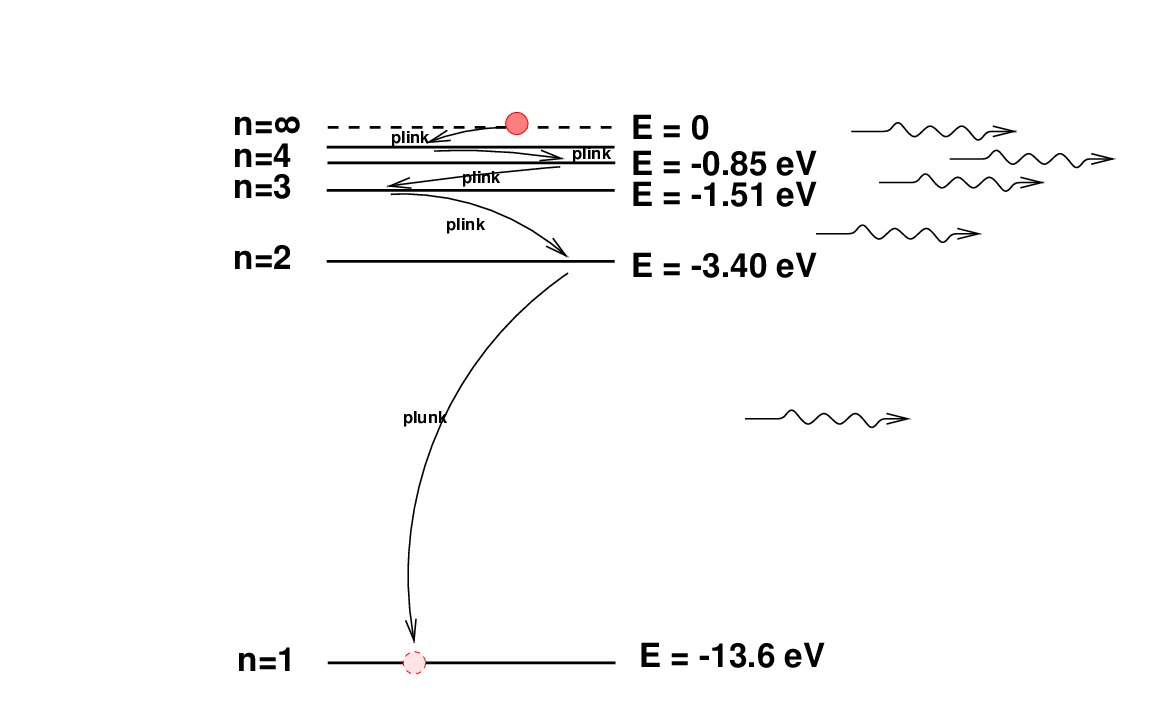

The electron is generally captured into a very high energy state, from which it will quickly jump down in a series of transitions until it reaches the ground state. Each transition causes the atom to emit a photon of energy equal to the difference in energy levels between the two states.

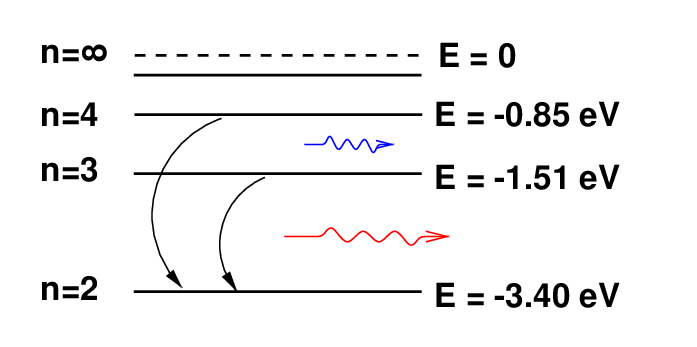

Pay attention to transitions which land in the n = 2 energy state: they are known as Balmer transitions. From an optical astronomers's point of view, the most important of these are the two shown in the diagram below.

start level end level diff in energy (eV) wavelength name

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

n=3 n=2 H-alpha

n=4 n=2 H-beta

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The H-alpha photons are the ones responsible for the beautiful bright red emission which is so distinctive a feature in many astronomical images.

Image courtesy of

Liron Gertsman

and

Astronomy Picture of the Day

Just how large will the radius, R, of the ionized region around the star be? The answer depends on the competition between the number of ionizing photons emitted by the star each second, NUV -- which destroys hydrogen atoms -- and the number of recombinations per second in the entire ionized region, Nrecomb -- which re-creates hydrogen atoms. The number of photons emitted by the star each second is some fixed number which depends on the size and temperature of the star (we're ignoring the slow evolution of the star for now). The larger the radius R, the larger the number of hydrogen atoms and therefore the number of protons which are available to recombine. So if the number of photons is fixed, but the number of protons grows with radius R, at some point, the two numbers must be equal.

We'll consider the simplest case: a spherical cloud of uniform density which has reach an equilibrium in size. Let's set up some variables:

We'll treat the number of ionizing photons emitted by the star each second, NUV, as a number that we can just look up (it depends on the nature of the star -- more on that in a later section).

Its matching quantity, the number of recombinations per second, Nrecomb, takes a bit of work to figure out. Let's get to work.

The number of protons in the ionized region is simply its volume times the density of protons; that's easy enough.

Each proton remains isolated for some period of time before capturing a passing electron. Let's call the average time it takes for a proton to snag an electron the recombination time tr. In that case, the number of protons which re-combine each second must be

In a steady state, the rate number of ionizing photons per second must equal the number of recombinations per second, which means

Q: Can you write an equation for the equilibrium radius R

as a function of NUV and the other quantities?

Right.

If we could just figure out the recombination time tr, we'd be able to determine the typical size of HII regions.

So let's do that next.

Our goal in this section is to figure out the typical recombination time in the ionized region. In order to do that, we'll make a slight modification to a calculation we carried out a few lectures ago.

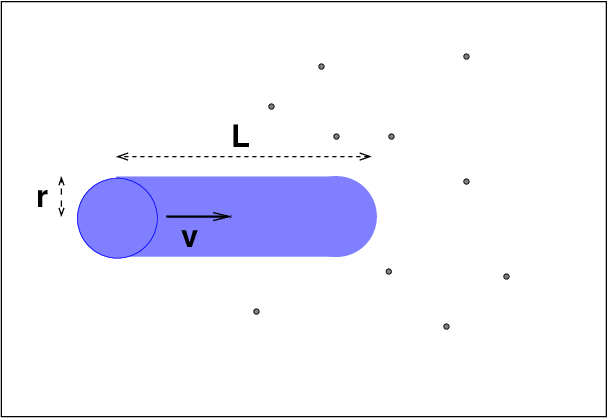

Remember our calculation of the mean free path of a particle in a cloud of gas? If an object of radius r travels at speed v through a gas of density n, then it will sweep out a cylindrical volume. When the distance it has travelled, L, is large enough that the swept-out volume is equal to the typical volume per particle in the gas, we can conclude that the object has collided with one of the particles.

Let's approximate the proton as a small hard sphere of radius r, so that its cross section is σ = π r2. It's not really just a little ball, and the physics of the collision is much more complicated; we'll come back to that in a few moments. Just go with this simplication for now.

In this ionized medium, free protons and free electrons are flying around at random. If the two sets of particles share the same kinetic temperature T (and we'll assume that they do), then the electrons -- being much less massive -- will travel at much higher speed than the protons. Since it's the relative motion of the proton and the electrons which matters for a collision, the speed we should use in this calculation is the thermal speed of the electrons: ve.

Putting it all together, we can write the volume swept out by the proton over the recombination time as

The volume occupied by each free electron in the gas is

A collision will occur when enough time has passed that

Q: Solve this equation for the recombination time

in terms of the other quantities.

Yes, yes, very good:

Our goal is to find a numerical value for the recombination time, so that we can use it to estimate the typical size of an HII region. We can adopt a value for the density of electrons in the ionized region based on observations, but what about the other two terms: the speed of electrons in the gas, and the cross section for collisions with a proton?

We need to start choosing some canonical values for some of these quantities. Here are some reasonable numbers:

The thermal velocity of electrons in this plasma is simply

Q: What is the typical velocity of electrons in an HII region?

The cross section for collision between a proton and an electron is a somewhat flexible quantity. It depends on the relative velocities of the particles, since the faster they pass each other, the less time the electric force will have to alter their trajectories. One can find tables showing the effective cross section for capture as a function of gas temperature in standard references; I've used one to select a value appropriate for our situation.

Okay, we are now ready to compute the typical recombination time in the ionized region.

Q: What is the recombination time?

Express your answer in seconds and in years.

You should find a very long time. Once a hydrogen atom has been ionized, it STAYS ionized. In other words, the great majority of all the hydrogen atoms in the HII region really are ionized, and the fraction of neutral atoms is tiny.

This recombination time time also indicates how long an HII region would continue to glow bright red if its source of ionizing photons were to disappear.

Phew. We finally have the information we need to answer the question, Just how large will the radius, R, of the ionized region around the star be?

The equation we derived earlier was

For our canonical situation, let's adopt the recombination time we derived above, as well as

Q: What is the typical radius of an HII region?

Express your answer in both meters and parsecs.

Recall 1 pc = 3.08 x 1016 meters.

This method of estimating the size of the ionized region around a hot star was first published by Bengt Stromgren in 1939, so astronomers often call this a Stromgren sphere.

Now, note that the density of the gas appears twice in the expression above. First, it occurs explicitly in the first term, as the density of protons raised to the negative one-third power. But it also is present in the recombination time, since tr goes like the reciprocal of the electron density. In a cloud of pure hydrogen, the proton and electron densities must be equal, so we can pull those two terms out and reveal how the size of the ionized region depends upon its density:

Should all stars be surrounded by bright-red glowing clouds of gas? What about the Sun? Are we on the Earth at the center of an HII region?

The key to creating an HII region is -- surprise, surprise -- being able to ionize hydrogen. If hydrogen atoms remain neutral, they won't cascade down from excited energy levels, emitting photons as they descend. If we continue to use "UV" as a shorthand for "photons with energies greater than 13.6 eV," then we can put it simply:

No UV, no HII region.

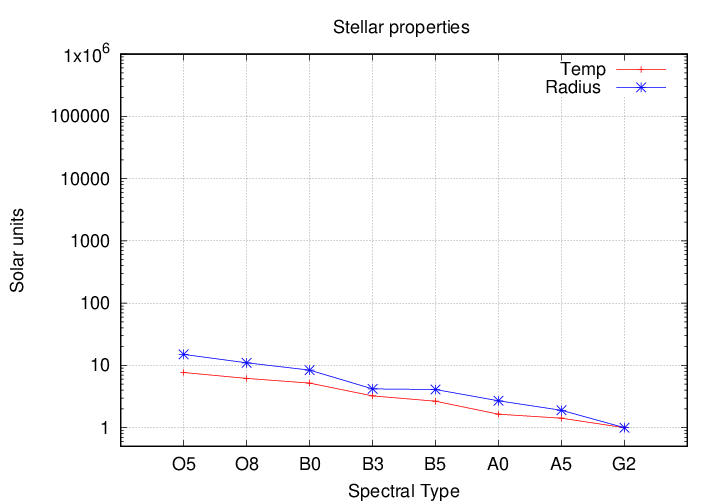

There are many different varieties of stars, over wide ranges of mass and temperature and so forth. Here's just a tiny sample:

spType T(K) L(solar) R(solar) M(solar)

---------------------------------------------------

O5 44500 790000 15 60

O8 35800 170000 11 23

B0 30000 52000 8.4 17.5

B3 18700 1900 4.2 7.6

B5 15400 830 4.1 5.9

A0 9520 54 2.7 2.9

A5 8200 14 1.9 2.0

G2 5780 1 1 1

---------------------------------------------------

Which of these factors might affect the number of ionizing photons emittedy by a star? Hmmmm.

Q: Which of the factors above determine the number

of ionizing photons emitted by a star?

The temperature and the radius both seem as if they ought to have some influence on the number of UV photons. Some of the stars in the table above are larger, or hotter, than the Sun -- but the differences aren't very dramatic ...

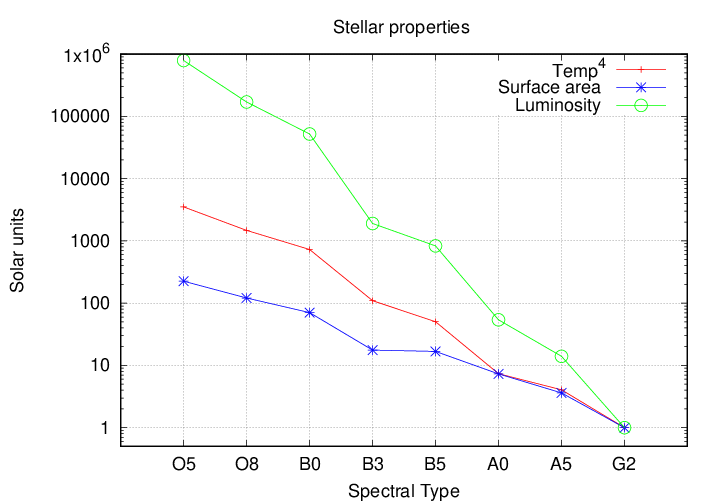

Wait a minute. How, QUANTITATIVELY, do the radius and the temperature of a star affect its ionizing luminosity?

Q: Ionizing flux depends on radius to the _________ Q: Ionizing flux depends on temperature to the _________

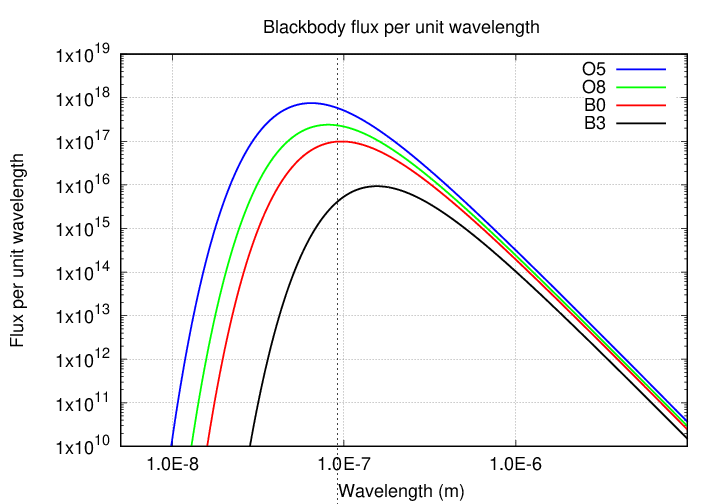

No -- wait. It's even worse than that. Remember that the peak wavelength (or energy) of the radiation produced by a blackbody changes with its temperature.

In order to produce a significant fraction of its output in the UV part of the spectrum, a blackbody needs to have a certain temperature ...

Q: The critical wavelength for ionizing hydrogen atoms

is λ = 91.2 nm. What is the temperature

of a blackbody which reaches its peak at that wavelength?

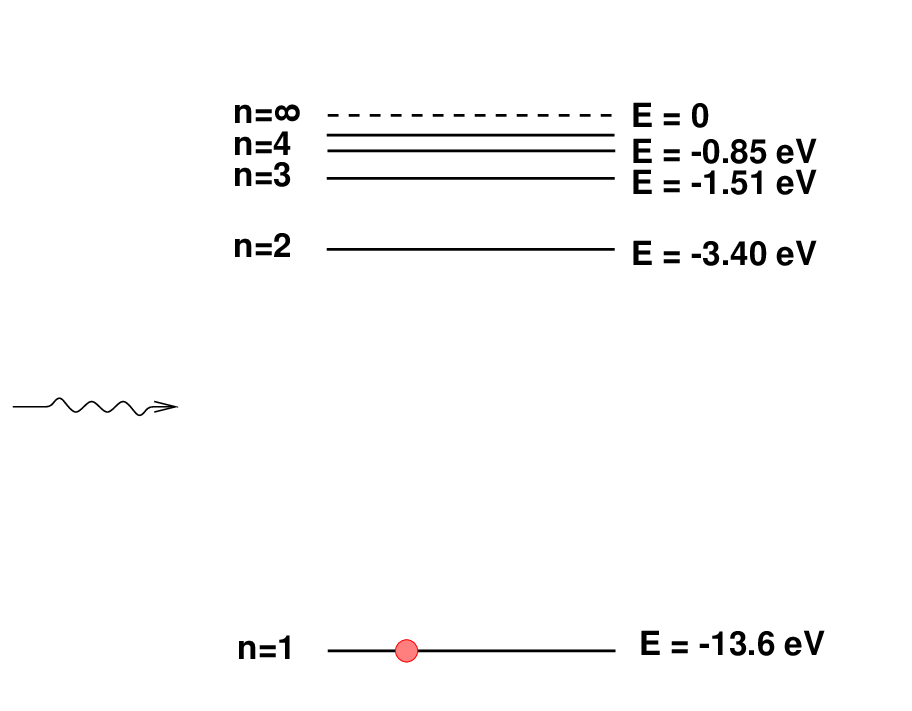

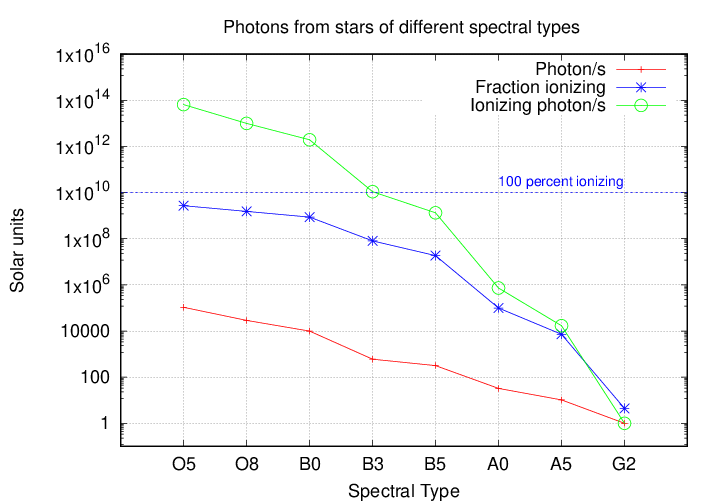

If we include all the effects of temperature and radius, then the difference between really hot stars and the Sun grows to stupendous size. In the graph below, the red line shows the number of photons of ALL energy emitted by a star, while the blue line shows the fraction of its photons which exceed the ionizing limit; the horizontal dashed line represents "100% of the photons are ionizing", and don't forget that the scale is logarithmic! Combining all these effects, the green line shows the number of ionizing photons emitted per second by a star of each type. Note the size of the difference between, say, an O8 star and a Sun-like star.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.