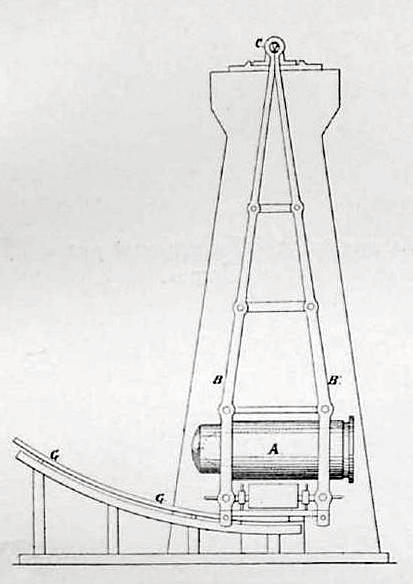

Image taken from Benjamin Robin's book New Principles of Gunnery, published in 1742.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, European armies gradually came to rely more and more on weapons based on gunpowder. Muskets, rifles, and artillery replaced bows and pikes as the primary focus of combat. Improving the range and accuracy of these weapons became crucial for countries which hoped to dominate the continent. Testing centers were set up to provide feedback to the engineers who were trying to come up with better mechanisms.

But just how does one measure the properties of, say, a rifle? For example, how can one determine whether a new recipe for gunpowder will yield a higher muzzle velocity? In the present high-tech age, one can simply capture high-speed video of the bullet leaving the muzzle; a frame-by-frame analysis will yield the speed of the bullet with high precision. But there were no cameras back in the 1700s, nor any stopwatches.

Q: How can one measure the muzzle velocity of a rifle using

simple equipment?

Sure, one option is to fire the gun over a large, open field at a distant target. But the results will depend on the weather and the wind, and the target must be very large if one is probing the extreme range of a weapon. Moreover, because the results are affected by local conditions, one must carry out a large number of trials to reduce the resulting noise in the measurements. Finally, firing live ammunition long distances over open areas is just asking for accidents to occur, especially when multiple teams of workers are required to carry out tasks at each end of the firing range.

Around the year 1740, an English engineer named Benjamin Robin came up with a better idea. His method did not require the projectile to travel a long distance, avoiding many of the weather-based issues; in fact, his device could be placed inside a building. His invention, the ballistic pendulum, was a simple one: a pendulum with a very thick hanging weight.

Image taken from Benjamin Robin's book

New Principles of Gunnery, published in 1742.

This illustration of a much later version shows it more clearly. The idea is simple:

Image taken from

a Russian artillery manual

of the early twentieth century.

The maximum angle to which the pendulum swings is related precisely to the initial speed (and mass) of the projectile.

In today's class, you'll use measurements from a real ballistic pendulum to determine the velocity of a steel ball fired by a spring-powered gun.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.