Right Ascension and Declination

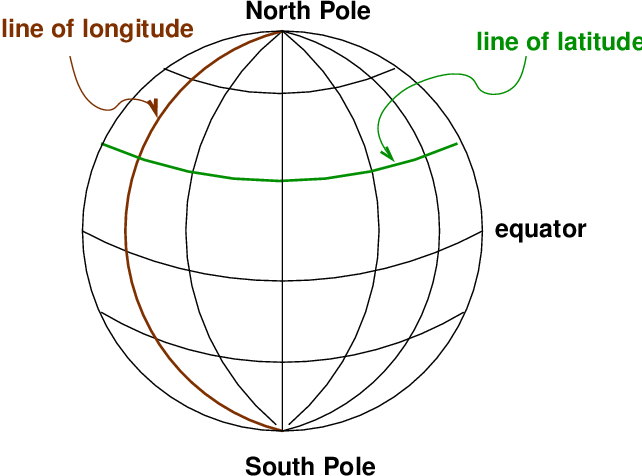

On Earth, one way to describe a location is with a coordinate system which is fixed to the Earth's surface.

The system is oriented by the spin axis of the Earth, and has special points at the North and South Poles. We use lines of latitude and longitude to demarcate the surface. It's obvious that latitude is measured away from the equator. But where is the starting point for longitude? There is no "obvious" choice. After a lot of dickering, European nations finally decided to use the location of the Greenwich Observatory in England as the starting point for longitude.

Q: Why was Greenwich, England, chosen as the "center" of the

longitude system?

There are several ways to specify a location -- for example, that of the RIT Observatory. One can use degrees:

latitude 43.0758 degrees North, longitude 77.6647 degrees West of Greenwich

Or degrees, minutes and seconds:

latitude 43:04:33 North, longitude 77:39:53 West

Or, in the case of longitude, one can measure in time zones. The sun will set at the RIT Observatory about 5 hours and 11 minutes later than it does at Greenwich, so one could say

latitude 43:04:33 North, longitude 05 hours 11 minutes West

Latitude and longitude are global coordinates: they are the same for all observers. Everyone agrees, for example, that Rochester is at

Rochester: longitude 77 degrees West of Greenwich

latitude 43 degrees North of equator

Earth-centered coordinates: Right Ascension and Declination

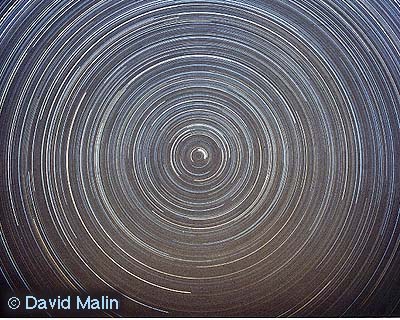

On can make a similar coordinate system which is "fixed to the sky":

Once again, we use the Earth's rotation axis to orient the coordinates. There are two special places, the North and South Celestial Poles. As the Earth rotates (to the East), the celestial sphere appears to rotate (to the West). Stars appear to move in circles: small ones near the celestial poles, and large ones close to the celestial equator:

Image copyright

David Malin.

We again use two orthogonal coordinates to describe a position:

- Declination, like a celestial latitude

- Right Ascension, like a celestial longitude

Why do astronomers choose this coordinate system, connected to the Earth?

Well, the main reason is that astronomers, too, are stuck to the Earth. We all live on the surface of the Earth, and we make our measurements from the surface. Suppose I set up a telescope in a fixed position, pointing in any particular direction, and lock it into place. As the Earth rotates, stars will appear to sweep through my telescope's eyepiece from East to West.

But not all stars. My telescope will only see a few stars, those with a particular Declination. Night after night, those same stars will pass through the eyepiece -- making it easy for me to measure their positions.

A week later, if I shift my telescope to point slightly higher above the horizon, a new set of stars will move through my telescope -- stars with a slightly different Declination. Once again, I can simply sit and watch them drift by as time passes, and measure their positions carefully.

Only if we pick an Earth-centered coordinate system will a fixed telescope observe stars within a narrow range of some coordinate. Because it simplifies the process of measuring stellar positions, an Earth-centered coordinate system is convenient for astronomers.

Once again, there are several ways to express a location. The star Sirius, for example, can be described as at

Right Ascension 101.287 degrees, Declination -16.716 degrees

We can also express the Declination in Degrees:ArcMinutes:ArcSeconds, just as we do for latitude; and, as usual, there are 360 degrees around a full circle. For Right Ascension, astronomers always use the convention of Hours:Minutes:Seconds. There are 24 hours of RA around a circle in the sky, because it takes 24 hours for the Sun to move all the way from sunrise to the next sunrise.

Right Ascension 06:45:09, Declination -16:42:58meaning

- the Right Ascension is 6 hours, 45 minutes, 09 seconds

- the Declination is -16 degrees, 42 arcminutes, 58 arcseconds

What's the difference between an "arcminute" and a "minute"?

- one degree is divided into 60 arcminutes

- one arcminutes is divided into 60 arcseconds. Therefore, there are 3600 arcseconds in one degree

- one hour of time is divided into 60 minutes of time

- one minutes of time is divided into 60 seconds of time. Therefore, there are 3600 seconds of time in one hour of time

Like latitude and longitude, RA and Dec are global coordinates: they are the same for all observers. Everyone agrees, for example, that Sirius is at

Sirius: RA 101.287 degrees

Dec -16.716 degrees

These two angles specify uniquely the direction of

any object in the sky.

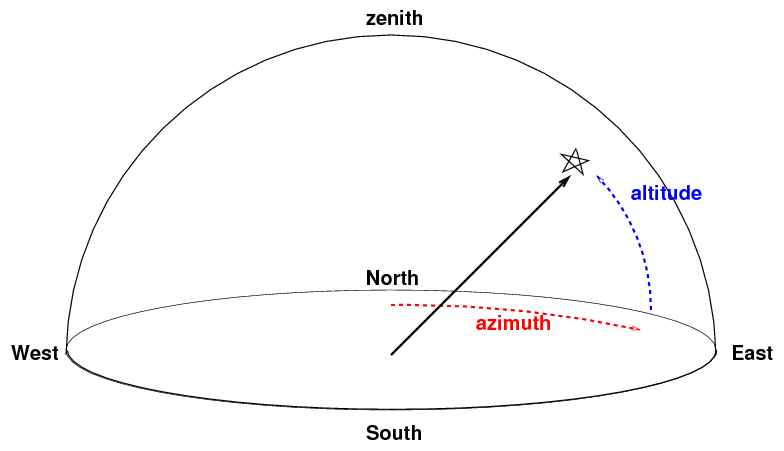

Some telescopes have

alt-az mounts

which swivel in these two perpendicular axes;

camera tripods and tank turrets are other examples

of alt-az devices.

The altitude of an object is especially important from

an practical point of view:

any object which has an altitude less than zero is below

the horizon, and hence inaccessible.

Moreover, the altitude of an object is related to its

airmass,

a measure of how much air the light from that object

must traverse to reach the observer.

The larger the airmass, the more light is scattered or

absorbed by the atmosphere, and hence the fainter an

object will appear.

However, note that (alt, az) are local,

not global, coordinates:

two observers at different locations on Earth

will not agree on the (alt, az) position of an object.

Moreover, as the Earth rotates, an object in the sky appears to

move from East to West,

so even a single observer will

see its (alt, az) position change from moment to moment.

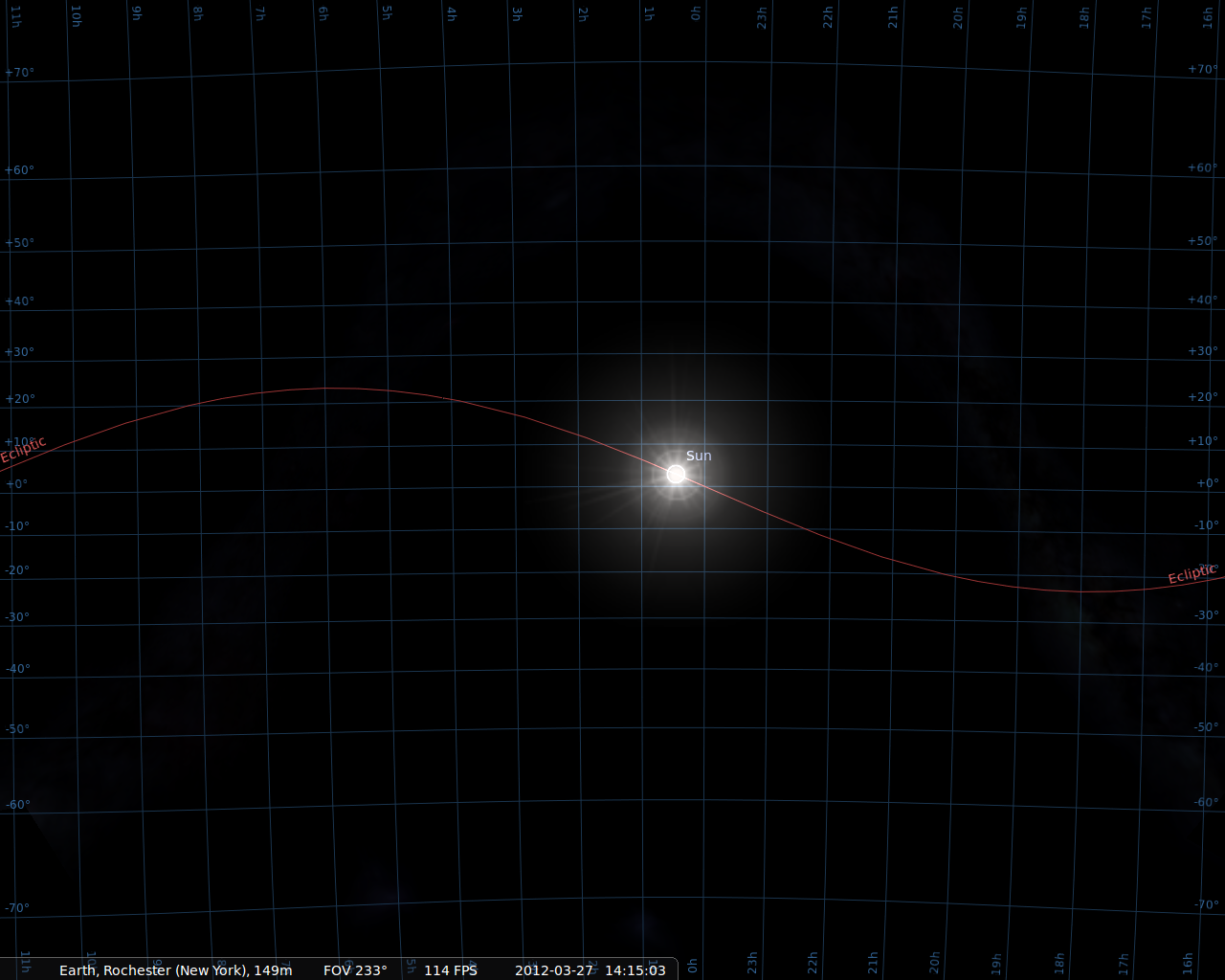

The ecliptic coordinate system is convenient when

dealing with objects in the solar system:

they are concentrated towards the ecliptic equator:

If you zoom in, you can see that the major planets

lie slightly above or below the ecliptic equator,

because their orbits around the Sun are inclined

slightly with respect to the Earth's.

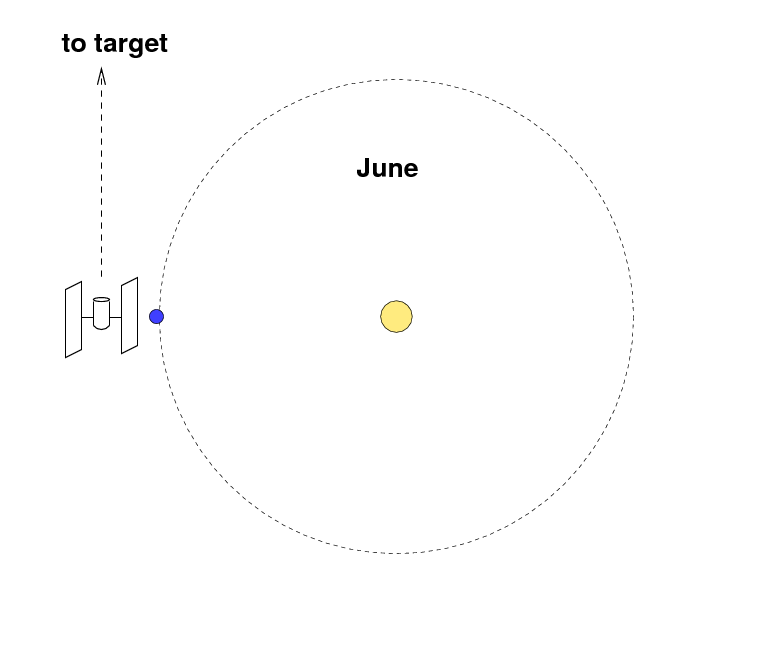

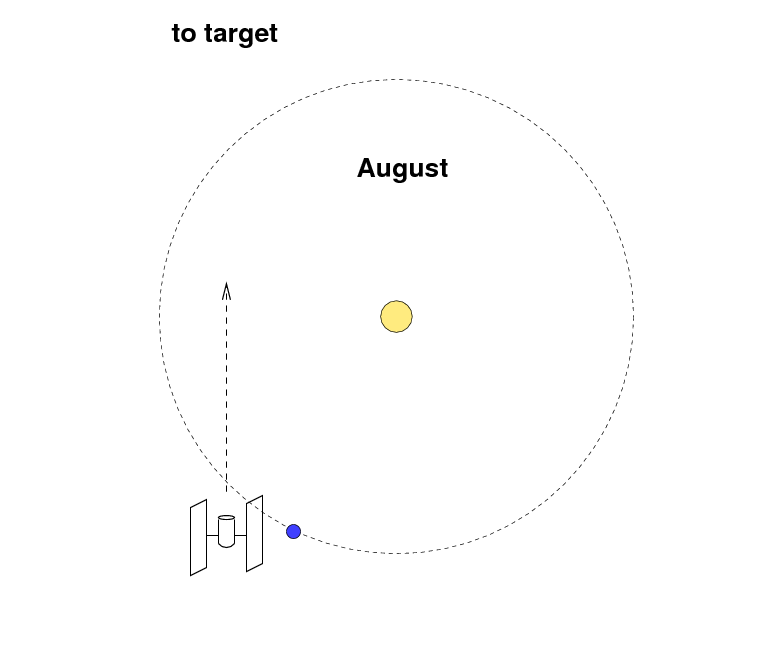

Ecliptic coordinates can also be important when you

want to avoid the solar system.

Telescopes in space, such as the Hubble Space Telescope

or the Chandra X-ray Telescope,

cannot point close to the Sun

(or else they might suffer damage to their detectors).

For some purposes, astronomers want to make very,

very long exposures: days or even weeks long.

During such a long exposure, the Earth may move a

significant fraction of its entire orbit,

which can cause a target originally far from the Sun ....

... to move closer to the Sun, from the telescope's point

of view.

Therefore, astronomers sometimes choose their

very deep fields

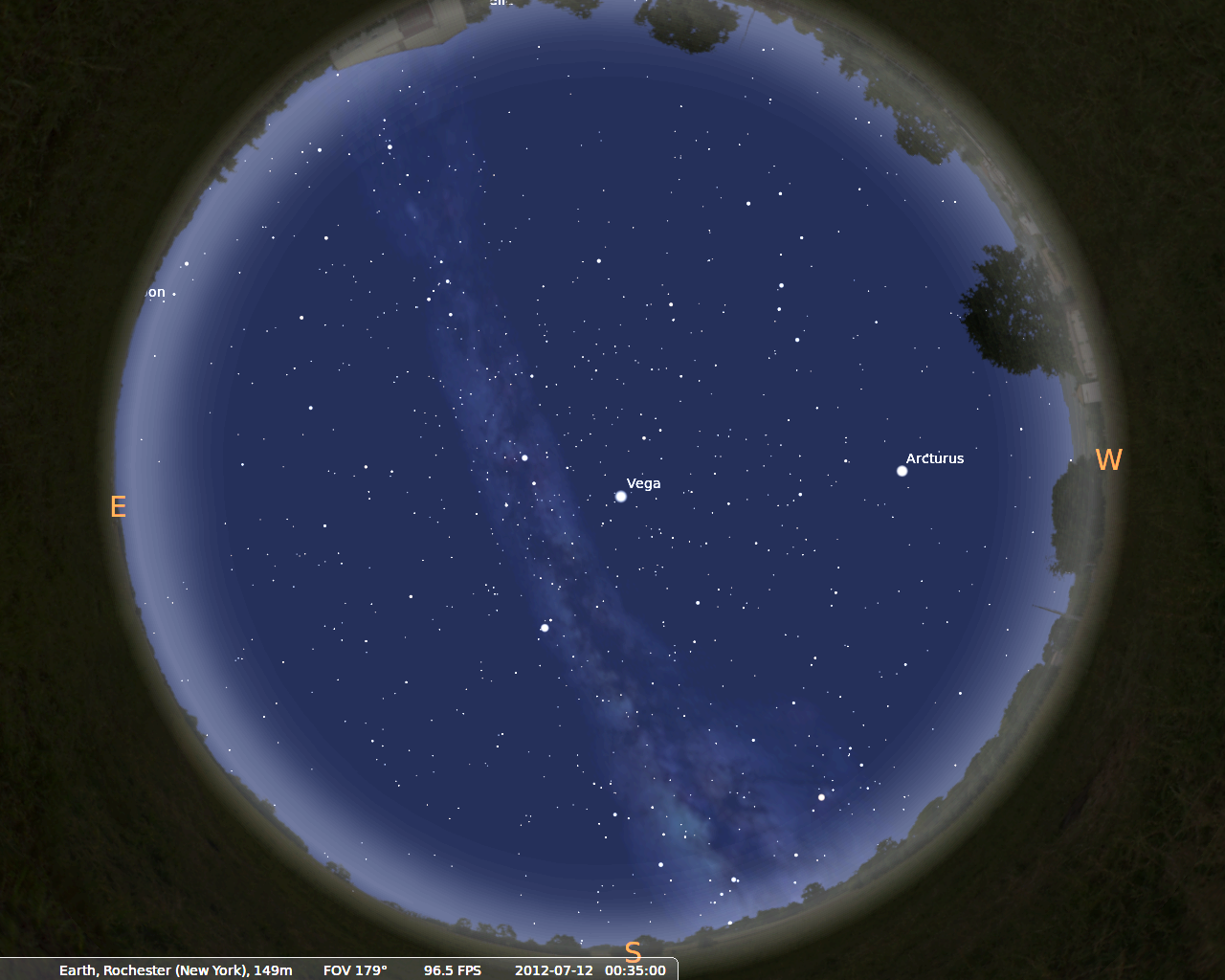

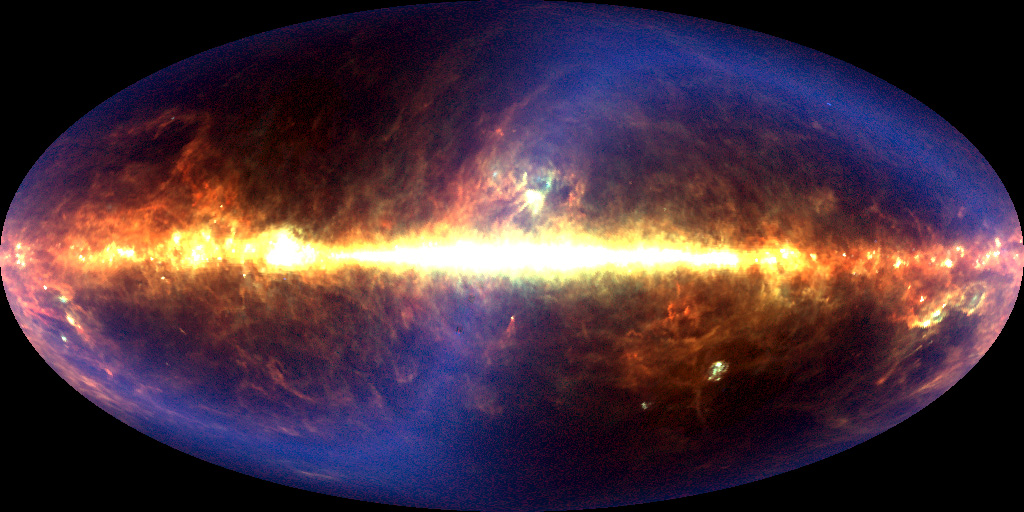

On a warm July evening in Rochester, the Milky Way

stretches overhead, with the galactic center

just above the southern horizon.

If you make a map of the sky in galactic coordinates,

the Milky Way runs right across the middle.

The section we see in the summer sky from Rochester is

in mostly the left half of this map.

An infrared map of the sky in galactic coordinates

made by the COBE satellite is dominated by emission

from dust in the Milky Way,

but also shows a faint band of light

due to emission by dust particles in the

solar system.

Note that the plane of the solar system is tilted by almost

ninety degrees relative to the plane of the Milky Way.

Is this a good idea?

Perhaps you should see where it lies with respect to the

Milky Way, by converting its RA and Dec

to galactic coordinates.

There are several ways to do this --

I recommend one of these tools:

Last modified by MWR 3/13/2012

Altitude and Azimuth

These two coordinates,

altitude (or "alt")

and

azimuth (or "az"),

are centered on the observer.

They are the same coordinates that an

artillery officer would use to describe the

direction of a distant target --

so just imagine that your telescope is

a big gun.

Ecliptic (Solar System) coordinates

For objects within our solar system --

planets, asteroids, comets --

it often helps to use a coordinate system

centered on the Sun, with its equator running along

the plane of the planetary orbits.

We call this the ecliptic coordinate system.

Q: Is the ecliptic coordinate system a "global"

or "local" system? In other words, will all

observers agree on the ecliptic coordinates

of one particular object?

Galactic Coordinates

One more set of coordinates comes into play

if one studies the distribution of stars

within our Milky Way Galaxy,

or the distribution of other galaxies

in the far reaches of space.

Map courtesy of the

Lund Observatory

Q: Is the galactic coordinate system a "global"

or "local" system? In other words, will all

observers agree on the galactic coordinates

of one particular object?

Converting between coordinates

Suppose that you know the coordinates of an object

in one system, but you need to know its

coordinates in a different system.

For example, someone tells you that you should

consider using HST to study a quasar located at

RA = 18:14:15 Dec = -29:03:39

Homework

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.